As I child, I lived at home and walked, ran, or rode my bike to the public schools in my town. I would leave in the morning, often arriving early to hang out or participate in activities with friends until the school admitted us to start our day of classes. Then, at the end of the school day, I would return home.

It was a rare thing for me to be involved in an activity that took me away from home for more than a night or two. Other than a one week long music “camp,” I did not experience an educational environment where it doubled as my home until I attended college.

Suddenly, the Student Post Office (SPO) box was my tether to the rest of the world - but especially my family and friends who resided “out there.” It was a daily ritual to check the “SPOs” in the morning after breakfast and in the evening at dinner time.

Now, imagine a time where it wasn’t possible to pick up a phone or hop in a car to visit. A young person living away from home at a boarding school probably felt that the outside world, and their family, was very far away.

When the post didn’t come to you

Mail pick up and delivery for the rural spaces in the United States were the exception to the rule in the 1850s - 1870s. In fact, Rural Free Delivery would not become more commonplace in the US until the 1890s.

So what could you do if you were a student or staff member at a rural boarding school and you wanted to remain connected with your family? The obvious answer is to find someone that would carry your letters to and from the closest post office.

Now, if your school was the size of the Westtown Boarding School, located in southeast Pennsylvania, there were going to be a lot of people hoping to send (and receive) letters on a regular basis. This was especially true given attendees would be at the school for up to a year before having a chance to go home.

If we estimate that 200 students and staff wrote someone every week, ten thousand letters would have to be carried out in a year. And a similar number probably came in. And this wouldn’t account for packages and other mail items.

Until 1858, the nearest post office was four miles distant in the town of West Chester. Enrollment at the boarding school was somewhere between 200 and 250 students in the 1850s. It is not hard to come to the conclusion that regular trips to West Chester were going to result in many bundles of letters and packages coming from and going to that post office.

A carriage drawn by a couple of work horses might travel at speeds between 3 and 8 miles per hour. So, it is not a bad assumption to assume that each trip would include two hours of travel time. Also, time did not stop as cargo and passengers were loaded and unloaded. Barring any additional income from the trip, the expense for carrying the mail likely came to hundreds of dollars each year.

Yes, I know that doesn’t sound like much. But every 1850s dollar is the equivalent of $40 today. So, it was enough to get some attention.

Since postage was required to mail letters in the 1850s, Westtown Boarding School maintained supplies of US postage stamps that students and staff could purchase for their outbound letters. And, starting in 1853, students were required to purchase a special label (or stamp) produced specifically for the school.

The Westtown School Committee (which could be likened to a supervisory board) added a fee for each letter sent out by students at the school. They came to an agreement with lithographer P.S. Duval to create a printing stone and print tags or labels that the school could sell for 2 cents each along with the US postage students would need. The first delivery of these stamps was in April of 1853, but the fee likely did not go into effect until the Winter school session started in November.

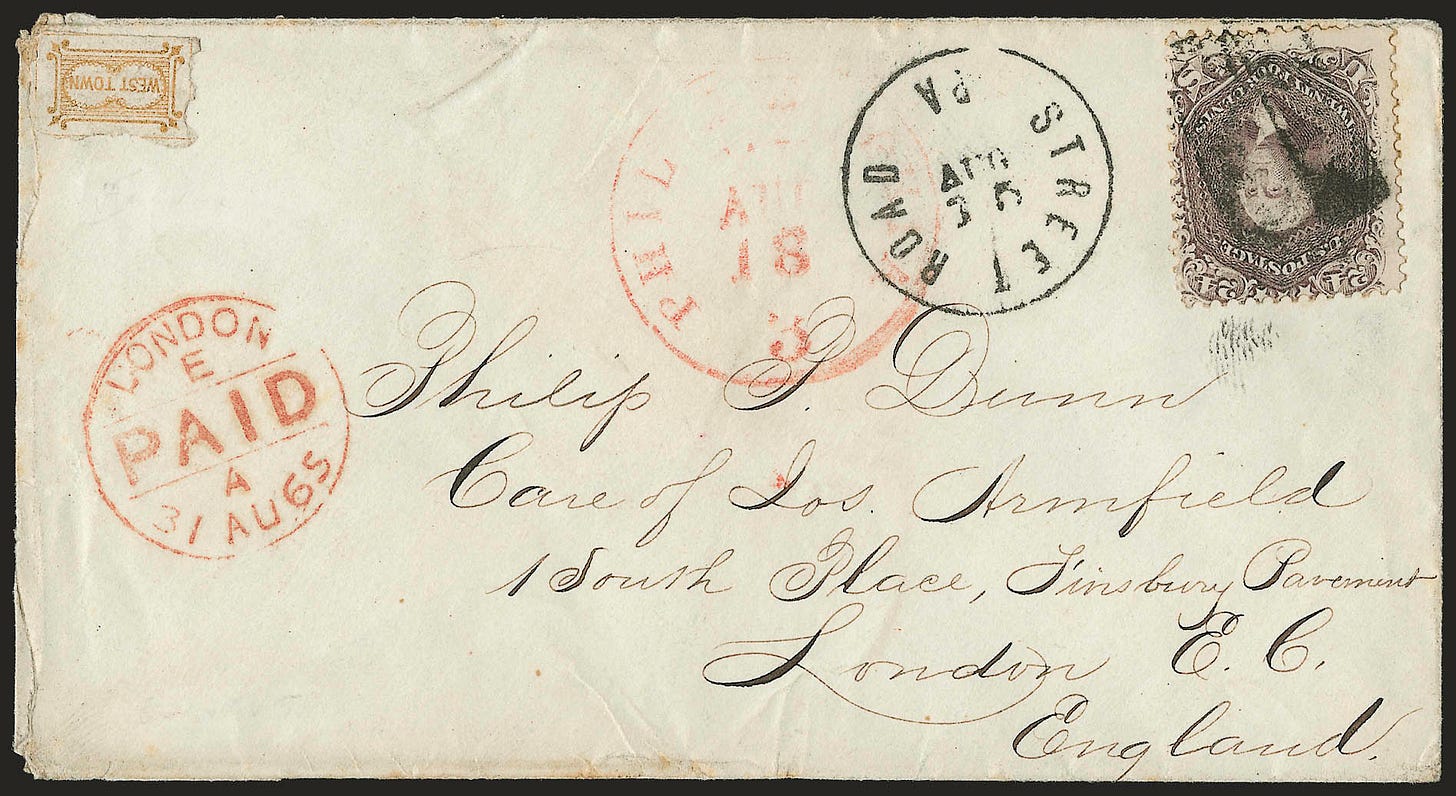

The Westtown local stamp shown above was printed by a different contractor, Thomas Sinclaire, who began producing these tags/labels for the school in the 1860s. This particular stamp was probably a part of a shipment of 30,000 that was recorded to have been paid for in November of 1864.

The design of this stamp did change from its first printing in 1853, to its last in 1878. Work by Robert Brinton and expanded on by Arthur B. Gregg, identified seven different types, or designs, that can help us to determine when a stamp was printed. The stamp shown here is a type VI, which is identified as having only one printing (or more accurately, delivery) of 30,000 in 1864.

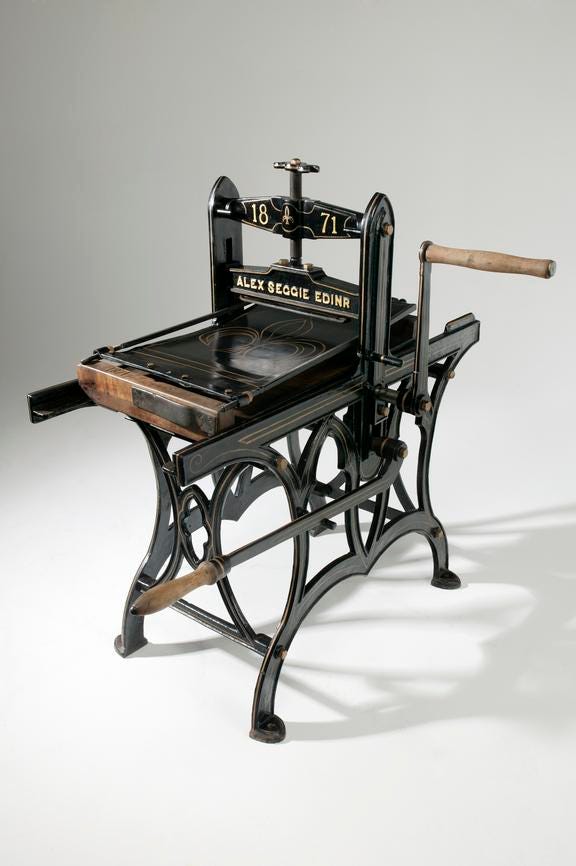

A quick sidebar about lithography

Lithography is a type of printing where a flat stone or metal plate has the design drawn on it with a greasy pencil or similar medium. Using various chemical reactions, the design area is “etched” into the stone or plate. When the plate is inked, the design area will allow the oil-based ink to adhere, but the water content of the rest of the plate will repel the ink.

Once a plate is inked, paper is pressed onto the plate to receive the design.

If the words don’t make sense, I suggest you go to this excellent demonstration of lithography on the Met’s page. What they show there is much easier to follow and much more accurate than my attempt to get it done in less than 100 words.

What got me started on the Westtown topic in the first place?

As is usually the case, my interest in the topic was spurred by an actual postal history artifact. The envelope shown above entered the mail at “Street Road,” Pennsylvania on August 15, 1865. It was taken to the Philadelphia exchange office and crossed the Atlantic on a ship that departed New York Harbor. It arrived at the London exchange office on August 31.

A 24-cent US postage stamp pays the cost of a simple letter traveling from the US to the UK and can be seen at the top right of the envelope.

We can determine that the letter originated at the Westtown Boarding School because the Westtown local stamp is affixed at the top left AND, at the time this letter was mailed, the Street Road rail station was the location of the closest post office.

There are, likely, well over one hundred surviving covers that bear a Westtown local stamp showing evidence of the 2 cent carriage fee from the school to the closest post office. However, the most recent accounting for existing covers that I am aware of was by Albert Maris (as reported by Gregg). That census indicates there were 74 covers known in 1949.

Most of these letters were sent to family located in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Ohio, Indiana, New York, Maryland and Virginia. As a result, most covers feature a 3-cent US postage stamp to pay the cost of a simple letter. This example, on the on the other hand, appears to be the only surviving example of a Westtown local on a letter that crossed the Atlantic Ocean. It is most certainly the only example I have seen where the Westtown stamp is used in combination with a 24-cent stamp.

That’s pretty cool, as far as I’m concerned!

The majority of existing covers feature the Westtown local stamp on the back of the envelope, where it often served to help seal the envelope flap. But it is not uncommon to find them on the front of a cover. These stamps were not postmarked or defaced, like other postage, to prevent reuse. The only time they might obtain a postmark is if they were near the US postage stamp on the letter.

The train came to Street Road

It was 1859 when the train came to Street Road, not far from Westtown Boarding School.

The West Chester and Philadelphia Railroad Company initially wanted to run their line along Chester Creek and through the school’s farm. However, the General Committee rejected that plan and the railroad came no closer than a mile away, at the Street Road Station (Westtown Station in 1888).

The new railroad were willing to transport passengers, mail and other freight for the School to this station and an agreement was made to construct a house and platform there. Marshall Taylor was named agent for the station and a post office was established on March 4, 1859. In addition to the post office and train station, Elizabeth Taylor tended a small store inside the station. Both Marshall and Elizabeth would serve there for the next 30 years.

In addition to bringing mail to and from the Street Road Station, the Westtown School stage picked up and dropped off passengers at a cost of 15 cents. Though, during the Spring, when the dirt roads were muddy and many new students arrived, it was not unusual to see students walking from the station.

With the shorter distance, one might think that the extra cost for delivery of mail to and from the nearest post office might decrease or be removed altogether. But it was not until the beginning of the Winter Session in 1878 (November) that the 2 cent fee was removed.

The Dunn family - strong Westtown connections

The featured cover is addressed to Philip P. Dunn care of Joseph Armfield in London. Armfield was a prominent conservative voice for British Quakers at the time and it is possible that Dunn was repesenting either his community or the school in a meeting in London at the time. There were many questions regarding how the Friends should proceed given different realities in modern times - especially given the greater distance and related disconnection that came with the communities in North America.

Philip Palmer Dunn (1825-1891) was a former student (Winter term 1844) who would become a member of the Committee in charge of Westtown School in 1870. Simply knowing that the recipient of the letter attended and later served on the Committee provides us with plenty of reason for them to have received a letter with the Westtown local stamp attached. But, we also have a legitimate reason for their presence in London as well with the connection to Armfield.

In addition to Philip P. Dunn, I also find school entries for Elizabeth Dunn (May 1859), Sarah Dunn (May 1862) and Philip Dunn (May 1865) - all from Trenton, New Jersey. These would be appropriate ages for Philip’s children to be attending the school their father had attended.

Based on a search of Westtown Through the Years, 1799-1942 by Helen G. Hole, both Elizabeth and Sarah can be connected to parents Sarah E. and Philip P. Dunn through letters in the school’s collection. Additional research finds a family tree on FamilySearch for Philip Palmer Dunn that provides evidence that the younger Philip is their third child. Based on the writing style and the evidence of letters sent and received, I would guess this was written by Sarah, with Elizabeth likely to have graduated by 1865.

Another notation in the book by Hole is that Elizabeth (Chambers) Dunn was a teacher at the school who later married Philip Palmer Dunn. According the family search, Sarah E died in 1864 and the Find A Grave website shows 1868 as the beginning of this new union. With all three children at West Town or having entered adulthood, it would have been easier for Philip P to go to London. It also might explain his stronger connections with the school, joining the Committee along with Elizabeth C in 1870.

Unfortunately, Philip Palmer Dunn’s story ends on a sad note. The newsclipping from the Jersey City News reports that his death was due to declining health possibly caused by financial troubles.

Do you want to learn more?

The history of the Westtown Boarding School, established in 1799, can be found in multiple locations. Instead of reciting it here, I encourage you to check out any or all of the following to learn as much (or as little) as interests you.

Summary of Westtown School’s history on their website

Centennial History of Westtown Boarding School, 1799-1899 by Watson and Sarah Dewees

Westtown Through the Years, 1799-1942 by Helen G. Hole

A Brief History of Westtown Boarding School with a General Catalogue of Officers, Students, etc, published 1872.

Westtown School historical collections

The Westtown Local by Arthur B Gregg in The Penny Post, Official Journal of the Carriers and Locals Society, Vol 2 No 2, April 1992

A History of Westtown Township, Chester County, Pennsylvania by Arthur E James.

Westtown Train Station by Kevin Gallagher - viewed on Westtown’s website at some point in the last ten years, but it is no longer at the link I saved.

Well we’ve done it, once again! Another Postal History Sunday in the books! Thank you for joining me. Have a great remainder of your day and a fine week to come.

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack. And, some publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest.

Always interesting to learn more about the connection between railroads and the mail service. My father was born in the 1910's, when horses were still commonly used for both work and transportation. He reminded me that the smell of many localities was far different then! We often don't think about the amount of horse droppings that were deposited on the dirt roads of that time, or the labor involved of trying to keep that cleaned up in towns or other more populous locales.

Interesting that the school found a way to recover the cost of a buggy/coach ride to the train station!! I need to research American bicycle technology from that era, and wonder if the students were even allowed to possess one?

Rob, may I publish piece in the Collectors Club Philatelist (NY)? I really enjoyed it!

Best, Wayne wystamps@gmail.com