The Wreck of the North American

The Project

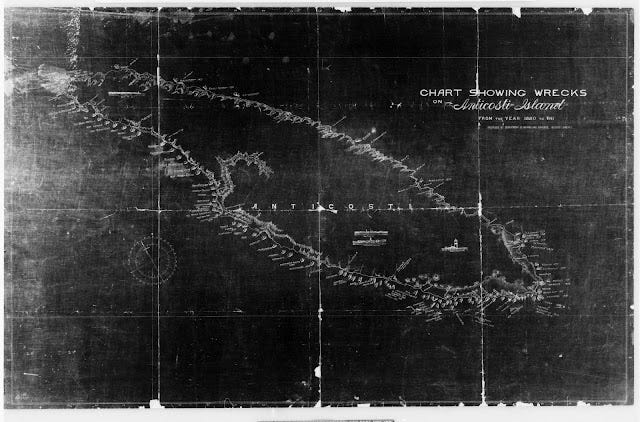

Navigating the Saint Lawrence Seaway could be tricky and it was not uncommon for ships to encounter difficulties in the 1800’s. In particular, the waters around Anticosti Island were most treacherous, with 106 recorded shipwrecks between 1870 and 1880 despite the existence of lighthouses by that time [1]. The sea lane was used for ocean traffic of all sorts, including mail packets, so it is possible to find postal history artifacts relating to accidents involving Anticosti Island. This article focuses on the travels of piece of mail that was placed aboard the North American, an Allan Line ship, in 1867.

Last Update: 1/ 13/18

The Perils of Anticosti

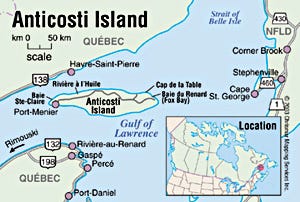

Anticosti Island can be found at the mouth of the St Lawrence Seaway as it enters the Gulf of Lawrence. Louis Jolliet, an explorer who initially believed the Seaway would provide water crossing to the Pacific Ocean, was awarded ownership of the island for his service to New France. Starting in 1680, he ran a fur trading and fishing business from the north shore of the island until it was raided by New Englanders in 1690. After that, his son divided and ran the island for the next 40 years [2]. By the 1860’s, an estimated 2000 ships passed the island each summer [1]. The island is now owned by the Quebec government, serving as a popular game and fishing reserve.

Anticosti Island is not a small obstruction in the St Lawrence Seaway, having 360 miles of shoreline and covering 3100 square miles. It is surrounded by a reef that can reach out a mile and a half from the visible shoreline. The reef, combined with a strong southeasterly changing to south current led to numerous shipwrecks resulting in varying degrees of loss to life and property [2].

Strong currents and reefs could certainly be mapped and lighthouses were built to help for nighttime navigation. However, experienced Seaway navigators recognized variations in compass readings could lead the unwary to run aground. An editorial to the Quebec Mercury in 1827 included observations from a mariner of that time:

“… it would be well that all ships at every opportunity should try experiments on the variation of the compass. I am fully of opinion that it does, and has increased. Since my first coming up the St. Lawrence, and very lately from experiments made, I found six degrees more variation than ever I expected, of my courses steered.” [3]

Wrecks on Anticosti Island from 1820-1911 by Department of Marine and Fisheries, Quebec Agency

These variations are known to be due to the shifting magnetic pole and its dramatic effect on compass readings as one goes further north on the globe. The treacherous nature of the waters around Anticosti caused many ships to employ a local navigator for the run into and out of the Seaway.

The Allan Line

The Province of Canada was very interested in supporting a steamship company that based itself out of Canada rather than continuing to be tied to the United Kingdom’s Cunard Line for trans-Atlantic mail sailings. In 1855, the Montreal Ocean Steamship Company (Allan Line) secured a contract to carry Canadian mails, which it proceeded to carry out upon the return of their ships from the Crimean War [4]. Allan Line ships departed Quebec (Riviere du Loup) in the summer when the St Lawrence Seaway was free of ice. During the winter months, the Allan Line left from Portland, Maine.

The Canadian and United States governments reached an agreement in November of 1859 that granted the Allan Line a contract to carry American mails [7]. Mail from the United States was sorted and placed in secured mailbags in United States exchange offices. Most mails carried by the Allan Line originated in the Detroit or Chicago offices. However, some mailbags from Boston and New York were sent on to Portland to be placed on board Allan Line mail packets when it was determined that this would be earliest mail packet departure. Normally, each piece of mail was hand stamped with a red (paid) or black (unpaid) marking that included the city name of the exchange office and a date. Chicago, on the other hand, often employed a credit marking that gave the amount credited to the foreign mail service with the word ‘cents’ in an arc underneath. Other offices typically used the date the ship was scheduled to leave port in a standard circular date stamp marking. Mailbags left the Detroit and Chicago offices via the Grand Trunk Railroad to their Quebec (summer) or Portland (winter) destinations [5].

The North American

The North American was a single screw, 1715 gross ton ship that was originally named the Briton at the point William Denny & Brothers laid the keel in 1855. The ship was launched as the North American on January 26, 1856 and took her maiden voyage from Liverpool to Quebec on April 23 of that same year. The ship was able to accommodate 425 passengers and served as one of the fleet of mail packets for the Allan Line. In 1871, the ship was moved to a Liverpool – Norfolk – Baltimore route until it was sold in 1873. At this point, the ship was converted to a sailing vessel and was used as such until it went missing in 1885 during a trip from Melbourne to London [6].

On June 16 of 1867, the North American ran aground on the south shore reef of Anticosti Island outbound to the Atlantic Ocean from Quebec. All passengers and crew survived the incident, spending some time on the island. Accounts indicate that they enjoyed picnics of fresh trout and were treated well by a Mr. and Mrs. Burns, who lived on the island at that time. The home occupied by Mr. and Mrs. Burns was furnished with material from other wrecks and they had survived a shipwreck themselves fourteen years earlier [1]. The St George picked up the passengers and the mail, taking them to St. Johns, Newfoundland. As for the North American, it was successfully refloated and towed to Quebec for repairs. It resumed its services to the Allan Line on November 12, 1868.

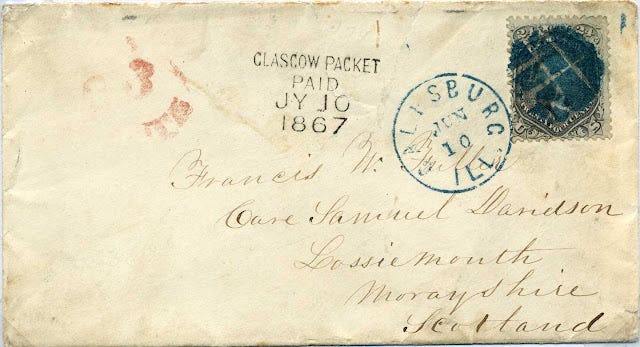

A Postal Artifact of the Grounding of the North American

Mails sent from the United States to Britain were governed by the 1848 agreement which remained in force until the end of 1867. Under this treaty, letters from the United States to Scotland required postage at the rate of 24 cents (1 shilling) per half ounce of letter weight. The cover illustrated nearby was prepaid with a 24 cent denomination adhesive from the 1861 series. The postage was then split between the British and US postal services in the following manner: 5 cents for US surface mail, 16 cents for the country who contracted the mail packet and 3 cents for British surface mail [5]. The red “3 cents” credit on the top left of this cover was applied in Chicago and indicated that 3 cents were owed to the British postal system by the US postal system. The Allan Line ship was under contract to carry mails with the United States, thus 16 cents were kept to defray the expense of that contract.

The Galesburg June 10 postmark in blue and the July 10 Glasgow receiving postmark indicate an abnormally long journey to get to its destination. Galesburg was not terribly far from an exchange office (Chicago) and the Grand Trunk Railroad should have delivered the mailbag containing this letter to Quebec in no less than two days time from Chicago. The crossing of the Atlantic typically took no more than 10 to 14 days, thus this letter was delayed for nearly half a month while it was in the mailbag.

The agreement with Canada dictated that United States mails were ‘closed’ in mailbags as they traveled over Canadian soil. No intermediate date stamps appear on the cover, which is consistent with its residing in a mailbag the entire time it was in transit from a U.S. exchange office (Chicago) to a British exchange office (Glasgow, Scotland). The receiving exchange office would open the mailbags and route each letter according to its destination. Some would be marked to go on to a more distant location (China, India, Australia, etc.) and placed in new mailbags to be put on ships for the appropriate destination. Others, such as this one, were placed in the local mail stream in order to be delivered to the intended recipient.

This cover provides sufficient evidence to show that the letter must have sailed on an Allan Line ship and that it was delayed. Shipping tables confirm that the North American was scheduled to leave Quebec in the middle of June in 1867 [7]. As a result, a timeline that illustrates the travels of this piece of mail can be reconstructed. After being placed in a mailbag in Chicago, the letter traveled by train to Quebec where it was placed on the North American prior to its departure on June 15. The next day, the North American ran aground at Anticosti. Soon after, the St George picked up the mailbags and took them to St John’s, Newfoundland. Another Allan Line mail packet, the Austrian, picked up the mailbags on its way to Quebec. The mailbags remained on the ship as it was prepared for its westward journey, which began on June 29. The Austrian arrived at Liverpool on July 9th, where it was then routed to Glasgow, completing a very interesting voyage.

Bibliography/Citations

[1] ] Mackay, D. Anticosti: The Untamed Island, McGraw-Hill, 1979.

[2] Henderson, B. Anticosti Island, KANAWA Magazine, Winter 2003 Issue, http://paddlingcanada.com/kanawa/issues/winter03.php, last viewed 1/15/06.

[3] Quebec Mercury #41, Tuesday, May 22, 1827, Page 241.

[4] Arnell, J.C. Steam and the North Atlantic Mails, Unitrade Press, 1986, p 224-5.

[5] Hargest, G.E. History of Letter Post Communication Between the United States and Europe 1845:1875, 2nd Ed, Quarterman Publications, 1975, p 133-136.

[6] Bonsor, N.R.P. North Atlantic Seaway, vol. 1, Prescott: T. Stephenson & Sons, 1955, p. 307.

[7] Hubbard, W. & Winter, R.F. North Atlantic mail Sailings 1840-1875, U.S. Philatelic Classics Society, 1988, 129-30,148.