Welcome to Postal History Sunday. This is the place and time where I share something about the postal history hobby I enjoy and, perhaps, you end up learning something new that interests you.

Take those troubles and worries and put them into a box. Then, put that box into another box and put THAT box into ANOTHER box. To keep this postal history related, you should then mail that box to yourself and when it arrives.... smash it with a hammer (who can name that animated movie reference?).

Oh wait, we don't want to smash potential postal history. Removed the lid with the stamps, address and postal markings first. Then, you can smash what remains with a hammer.

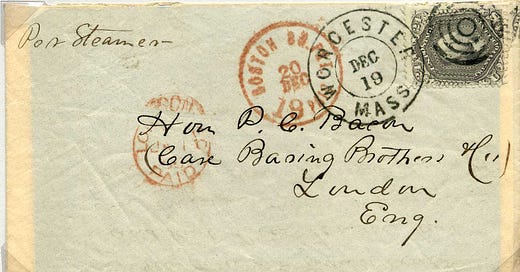

Sending a letter from Worcester to London

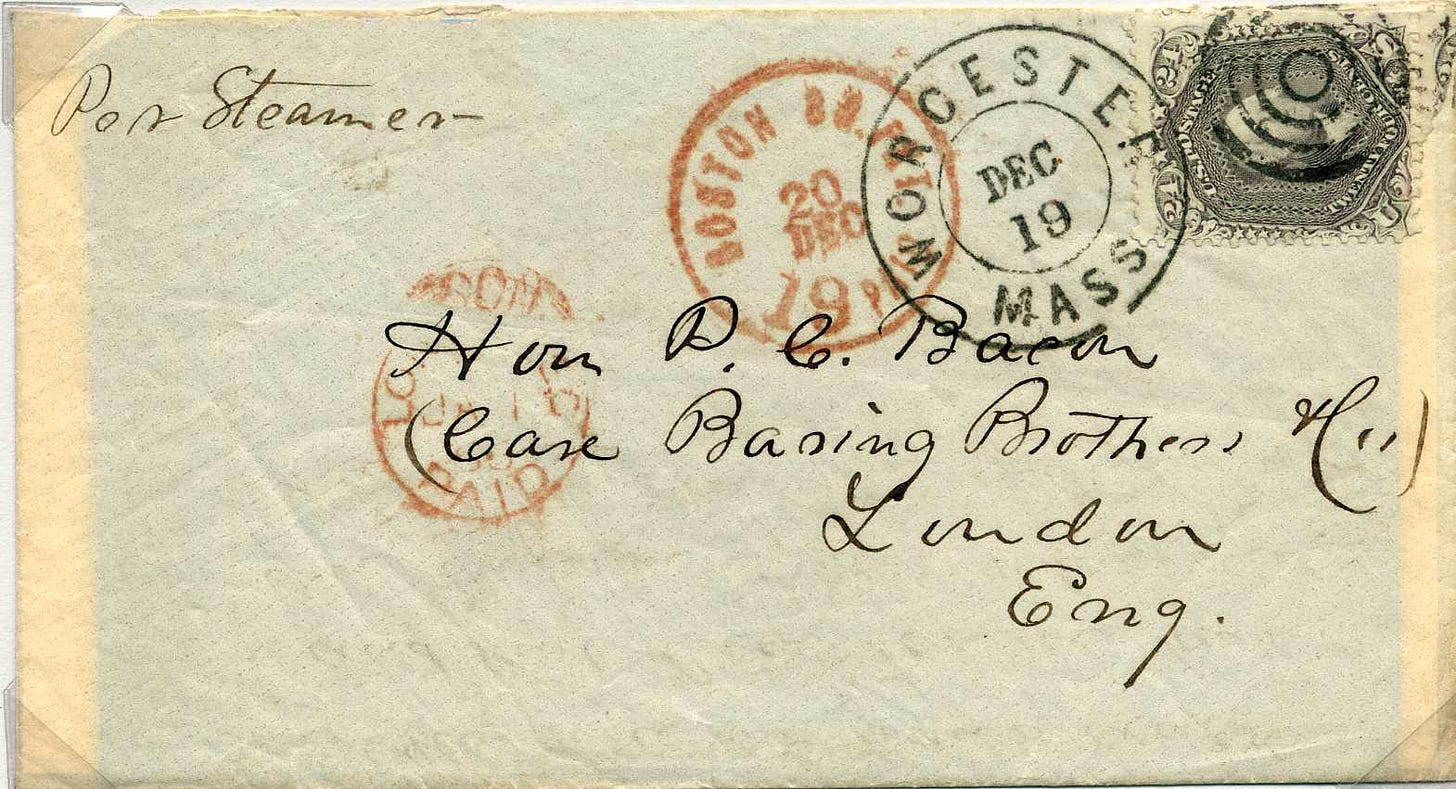

This letter was mailed on Dec 19, 1865 at Worcester, Mass and it left the next day on a Cunard Line steamship named Asia from Boston. The Asia landed at Queenstown (Cobh, Ireland) on December 31 where it unloaded this letter in a bag of mail destined for London. That bag was taken by train to Kingston and crossed the St Georges Channel to Holyhead on a steamship. From there to London, it was mostly railway until it was taken out of the mailbag and marked with the receiving exchange mark (the red London marking on the left side dated January 1, 1866).

I often find I get a better appreciation for things once I see a map and I can place where everything belongs in my head. Kingston is the port by Dublin and Queenstown is the port by Cork (Cobh). There was a regular steamer service between Kingston and Holyhead that carried passengers, goods and, of course, the mail.

Oh, and before I forget, the cost of mailing a letter from the United States to England was 24 cents as long as it did not weigh more than 1/2 ounce. This is good news, because the postage stamp has a denomination of 24 cents. That means this trip from the US to the UK was paid in full.

Opportunity Knocks

Some time ago, a couple of people asked if I would write about how I find covers for my postal history collection. While this post won't focus entirely on that, it makes some sense to talk about how I found the two envelopes I am featuring in this post.

Back when eBay was new(er), it was more common to find “under-priced” stamps and postal history. This is not to say that people were being cheated out of value. Instead, there were more collectors looking to sell directly to other collectors. These people did not have retail costs to pass on and ebay costs were minimal. They were often happy to make a sale that would be lower than a person with a business could accept.

You just needed to know which categories to look in and what keywords to use when you were looking. At one point in time, there was a postal history category for the United States inside of a larger "stamps" category. I regularly searched for items with a 24 cent stamp and almost always got the same list of the same offerings - most of which did not interest me.

One day I saw a auction lot that showed this item as the main photo, so I went to look at it. I found out then that there were actually two covers in the lot - and the price was very, VERY reasonable. I did not hesitate to bid and win the lot (and you'll see why later).

Today, the places I look are a bit more diverse, but the process isn’t terribly different. The main takeaways I can offer for finding material are:

You have to be willing to explore to find things, expecting to go through many items that aren’t something you want, and

You have to build up your own knowledge so you can recognize exceptional and different things when they show up - even if the person(s) selling it do not label it properly.

I am guessing most people are not going to be surprised by either of these takeaways. They can apply to a fairly wide range of interests. So, if those who asked the question were looking for a deeper insight beyond this, I am afraid you might be disappointed to learn that the answer is simply making serious efforts to explore and learn.

The Honorable P.C. Bacon goes to Europe

I was able to find a biography of the Honorable Peter Child Bacon (b. 11 Nov 1804, d. 7 Feb 1886) in this book that included the histories of several Massachusetts towns. (reference #2) P.C. Bacon was married to Mary Louisa Batchelder (b. 15 May 1815, d. 9 Jun 1886) and they appear to have had four sons and one daughter.

P.C. Bacon was a lawyer for a well-known and respected firm that bore his name and worked out of Worcester starting in 1844 (with prior work in Oxford and Dudley). He was the first representative from Worcester in the Massachusetts House of Representatives in 1848, when the city was first incorporated. One resource suggests he was elected as mayor of Worcester in 1851 and 1852 while another source lists him as the third mayor of Worcester, serving from 1849-51. It feels to me like the first source might be correct unless a person could serve as a Representative and the Mayor of a town concurrently.

Apparently, the Honorable P.C. Bacon took a trip to Europe towards the end of 1865, returning in January of 1866. While in Europe, it was common for a traveler to maintain a line of credit with a financial house for ease of travel and the coverage of expenses.

In addition to providing these monetary services, some financial houses would also provide mail forwarding or mail holding services for the traveler. This gave his family, friends, and business associates a method for reaching him if they needed to.

Oh, and just a reminder, there was no phone service in 1865... but I think you knew that!

But, what happens when P.C. Bacon goes home?

The line of credit with the financial house was typically purchased for the period of time that covered the travels of an individual. Any services rendered could be paid for by using the balance of the account. So, if the traveler went to Paris for a week, they could direct the financial agent to use money in their account to pay for the forwarding of mail from London (for example). But, what happens if a letter arrives and the line of credit was closed because the traveler had returned home?

The second envelope - the one that did not even get top billing in the ebay lot - illustrates exactly what happens.

The second letter was mailed in Worcester on January 2 of 1866 and arrived in London on January 13. Once again, a 24-cent postage stamp shows prepayment of the required postage to get from the US to the UK. However, there are no stamps paying for the necessary postage for the return journey from the UK to the US.

Baring Brothers & Co had managed Bacon's line of credit which was closed at the point they received this letter. They knew the Honorable P.C. Bacon had gone back to Worcester, so they mailed the letter to follow him home. Since he had not left them with a balance to cover forwarding costs for mail that arrived to late to catch him in Europe, they sent it back to Worcester on January 20 as an unpaid letter.

This letter retraced its steps - taking the train from London to Holyhead, crossing the St Georges to Kingston and then taking the train to Queenstown. Once there, it left on the Cunard Line's Africa on January 21 which arrived at February 3 in Boston.

Baring Brothers applied no stamp and did not pay ANY postage for the return trip to the United States. That means the recipient was required to pay the postage for that return trip.

Shown above is the key marking on the second cover that told me I had something unique and interesting. The marking is in black ink - just one indication that the item was received unpaid. But, what can make it confusing is that it gave two possibilities for the amount to pay.

24 cents or 32 cents. So, which was it?

Depreciated Currency in the 1860s

With the event of the Civil War, the United States had to abandon the gold standard that they had been using. In very simplified terms, paper money, prior to 1863, could be exchanged for a full equivalent value of precious metal. However, the demands of the war led the U.S. Treasury to issue what became known as "greenbacks" that were given legal tender status (you could purchase things with them), but you could not exchange them for a similar value in precious metal. In other words, the gold standard was abandoned from 1863 to the late 1870s - from the middle of the Civil War through the Reconstruction Period.

The value of these greenbacks was actually less than the same value in coins minted in precious metal (typically silver). As a result, the post office would accept 24 cents in coins OR 32 cents if greenbacks were used to pay your bill.

At least some of the reason for the US Post Office to be concerned about the difference between specie (precious metal) and paper money was that their postal agreement with the British Post Office was based on specie. If they collected only 24 cents in paper money, they would lose the US portion of the postage when they paid the British their share.

An excellent article titled A Brief History of the Gold Standard in the United States by Craig K Elwell provides a rundown that made sense to me, even though I am not big on the topic of monetary systems. If you make yourself read it fairly carefully, you may find that you begin to get an understanding as well. Or, you can just take my word for it - your call! And, if you’d like to look at the history of paying the postage (including reasons why postage stamps were actually used as currency during the war), I suggest this article by Richard Frajola.

Some postal historians enjoy looking for examples of depreciated currency markings that gives the recipient the choice to pay in greenbacks or specie (coins). In fact, there are numerous examples of these markings that can be found without much trouble. I am one postal historian who is fine with having just one example - and it's a good one because it has so many possible story lines.

But wait! There's more! P.C. Bacon's sons

I am occasionally amazed by all of the directions the research for a particular cover can take. In the process of chasing threads of information, I discovered a website that provides the Rosters and Geneologies of the 15th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry for the Civil War.

Apparently, P.C. Bacon had two sons who joined the 15th Massachusetts. The photo above, from that site, depicts Francis (Frank) and William Bacon. Frank was promoted to 2nd Lieutenant and transferred to the 102nd New York Volunteers on April 22, 1863. He died at the battle of Chancellorsville on May 2nd.

An obituary for Francis E. Bacon was published on 13 May 1863 at "The Worcester Palladium", Worcester, Worcester County, Massachusetts, as follows:

Death of Lieut. Bacon

We have to record, as another of the sad fatalities of this war, the death of lieut. Francis Bacon, son of Hon. Peter C. Bacon, of this city. He was killed at Chancellorsville, in the last great fight on the Rappahannock. He is spoken of by those who knew him best as a young man of more than ordinary promise. Two years ago, at the age of 19, he was among the first to go into the service as a private in the third battalion of Rifles; and soon after the expiration of the term of three months, for which that corps was enlisted, he entered the Fifteenth Massachusetts Regiment; and not long ago was appointed and commissioned a lieutenant in the 102d New York regiment. His early death, at the age of 21, is a loss to his friends and to the army.

William would also die in the Civil War at the Battle of Newmarket (Virginia) on May 15, 1864. One wonders exactly how the parents processed the loss of not one, but two, sons to this conflict. Was this trip a business trip or did both parents travel in an effort to find a new perspective? It’s likely I’ll never know. But, I am certain it was difficult to adjust to these losses.

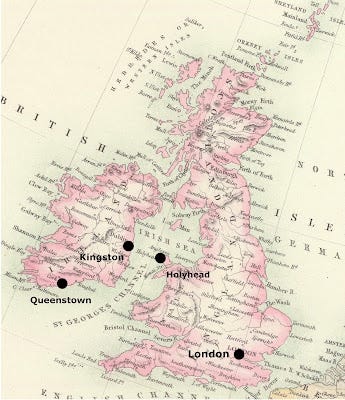

And more - Baring Brothers & Company

It turns out the Baring Brothers would have a key role in the Argentinian Banking Crisis of 1890-1 that the banking firm would survive with the intervention of the Bank of England. Even more interesting is that Baring Brothers would actually succumb to a "self-inflicted" investment crisis in 1994-5, over 100 years later.

This banking crisis apparently had some of its roots in the differences between paper money and specie (precious metals), which makes for an interesting parallel with the depreciated currency marking. I will not pretend to be a financial expert at this time and merely reference anyone who is interested to take the link above or find the third reference shown at the end of the post. However, I did select the quote below from page 67 of that reference to summarize the impact of the crisis.

The Baring Crisis originated in Argentina but it was felt all over the world, first in London. Borrowing from Britain had dominated the capital inflows of the 1880s boom. So when the bust arrived, its impact was sure to be felt by the major creditors. One famous institution had become deeply exposed to Argentine securities: the world’s largest merchant bank, Baring Brothers & Co., commonly known as Barings. Fortunately for them, there was a swift intervention by the Bank of England. The Governor was notified by telegraph to hastily return to the City from his sky vacation in Scotland and, before the markets knew anything of the parlous state of Barings’ balance sheet, the Bank cajoled a rescue package from a syndicate of private banks. This chain of events gave the crisis its name, but the nomenclature is unfortunate to the extent that it encourages a focus on events in Britain rather than Argentina. For the impact on the British economy, once the rescue was secured, turned out to be very limited indeed. Argentina did not escape so lightly.

The wonderful thing about all of this is that we can take any of the story-lines and dig into them deeper if we wish. The Bacon family was prominent enough that there are multiple opportunities to explore their lives and what they experienced. Baring Brothers had a long and involved history in banking, so if that story interests us, we could certainly do much more with it. But, from my perspective, the simple fact that a letter crossed the Atlantic Ocean in both directions to get to the recipient makes for a compelling story all by itself.

Thank you for joining me in this week's Postal History Sunday and I hope you learned something new. And if you didn't, I hope you enjoyed the process where I show that I learned several new things!

For those who might like to hunt down some of the resources for additional reading or exploration, here are some citations.

1. Rice, Franklin Pierce, Worcester of Eighteen Hundred and Ninety-Eight:Fifty Years a City : A Graphic Representation of Its Institutions, Industries, and Leaders, Worcester, Massachusetts: F.S. Blanchard & Company, p. 22.

2. Ammidown, Holmes, Historical Collections: Containing 1. The Reformation in France and II. The Histories of Seven Towns, 2nd Edition, Vol 1, New York, 1877.

3. Straining at the Anchor: The Argentine Currency Board and the Search for Macroeconomic Stability, 1880-1935 Eds: Gerardo della Paolera and Alan M. Taylor, University of Chicago Press, ISBN: 0-226-64556-8, URL: http://www.nber.org/books/paol01-1, January 2001.

4. Elwell, Craig K, Brief History of the Gold Standard in the United States, Congressional Research Service, June 23, 2011.

5. The website, Rosters and Genealogies of 15th Massachusetts Voluntary Infantry, lists resources for some of the information used to create their site. Site referenced Mar 12, 2021.

Have a fine remainder of your day and an excellent week to come!

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack. And, some publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest.