Thurn & Taxis - Postal History Sunday

Welcome to Postal History Sunday. PHS is cross-posted in this, the GFF Postal History blog and in the Genuine Faux Farm blog each Sunday - as long as the farmer can find it in him to write them. I try to write these blog posts so you, whether you already enjoy postal history or not, can enjoy the subject. And, maybe, we all learn something new in the process?

Before we get started, let's take all of those troubles and worries and put them under the oak tree. It's Fall here, so those leaves will just cover them up. Not long after, snowfall will cover the leaves. By the time the snow melts, we may not recognize those nasty worries anymore!

Put on the fuzzy slippers and grab a beverage. Let's see where this one takes us, shall we?

---------------------------------------

When I think about mail and postal systems, it is only natural for me to consider them based on my own experiences. For example, in the present day, I tend to think of the post as having a connection with a particular government or country.

That's why it can be a struggle sometimes to come to grips with the mail services provided by the princely house of Thurn and Taxis. At one point in time, they were couriers for a significant portion of Europe! By the time we get to the 1850s and 60s, their participation in postal matters was in decline and largely centered around certain German states. But, since that is the time period I like to study, that's where we will focus.

Rather than give you a typical history lesson, I thought I'd share by following the path my learning often takes - by starting with the pieces of mail that encourage me to dig and learn new things.

Northern and Southern Districts

One of my preferences is for pieces of mail that feature postage stamps paying for all or part of the required postal fees. The first postage stamps issued by Thurn and Taxis do not appear until 1852. The interesting thing about them is that they had to issue not one, but two, sets of stamps to handle their prepaid postage services.

Why?

It was a matter of different money systems.

North:

One thaler could be broken down into

30 silbergroschen

South:

One gulden could be broken down into

60 kreuzer

Stamps with each denomination were printed and used in their respective areas - which means a postal historian has more opportunities to.. um... get confused! I know. I was supposed to say that we have more opportunities to learn and explore. But, the diverse monetary systems in Europe during the 1800s can leave a person considering other alternatives for leisure time.

Let's start with a piece of letter mail from the northern districts that used the Thurn and Taxis postal services. The most common source of stamped Thurn and Taxis mail would be from the Hessian states, which were located in both the southern and northern district.

This letter was mailed from Cassel (Kassel) to Schlusselburg by Minden in May of 1854, a distance of about 200 km. Schlusselburg rested on the border of Hannover and Westphalia (Prussia) at the time this letter was sent.

It did not matter that this letter left one German state (Hessen-Kassel) and entered another (Prussia) because most of the German states and Austria had come to an agreement in 1850 to treat all mail within their borders as if it was internal, rather than foreign, mail. So, all we need to know about are the internal mail rates.

Internal mail for all members of the GAPU (German-Austrian Postal Union) was rated based on a combination of weight and distance.

Distance was measured in meilen (one meile was equal to roughly 7.4 kilometers) and weight in loth (16 2/3 grams). With a little math, we can determine that the trip from Cassel to Schlusselburg was a distance of 27 meilen. The rate for a simple letter weighing no more than 1 loth sent that distance was 2 silbergroschen (sgr) from June 1, 1850 until Aug 31, 1861.

And here is a piece of local mail that was sent in the southern district. To qualify for the lower, local letter mail rate, the distance could be no more than 3 meilen (about 22 km).

This letter originated in the city of Darmstadt, located in the southern Hessian territory, and was delivered in the city limits - that certainly should qualify for local mail!

The blue ink scrawl on this letter confused me for a little while, because in most areas of Europe, this might be an indicator that more postage was due. But, in this case, it is simply a postman's mark (or initials).

A Musical Interlude

Speaking of the postman making deliveries. The Thurn and Taxis postal carrier would ride on his horse or carriage and use a posthorn to announce arrival. If you have interest, you could hear the sound of a coach horn (used as a posthorn in England) at the Postal Museum's site.

Posthorn in collection of Grinnell College

If you are intrigued by the whole idea of a posthorn, let me encourage you to look more carefully at the two stamps at the top of this blog post. Can you find the posthorns in the design of each of those postage stamps?

And, if you would like to hear music featuring various types of posthorns, you could consider this music. But, what got my attention was the fact that the description found on that webpage cited a resource that gave more detail regarding the use of the posthorn:

According to the 1832 “Instruction on the Use of the Posthorn for Royal Hanover Postillions [mail carriers],” the primary purpose of the posthorn was “to signal the approach of postal conveyances and thus secure them unhindered and speedy attention.” Signal horns were also used at this time to indicate road conditions, to inform toll-keepers that an express mail coach was coming through and would require free passage, to signal to innkeepers ahead how many passengers were in need of lodging, whether a fresh team of horses was required, etc.

This just might be more than you ever wanted to know about posthorns, but I thought it was interesting.

One City, Different Postal Systems

The free city of Hamburg is an interesting case as they hosted various mail services, including posts for the Danes, Swedes and... Thurn and Taxis. An individual in the city could choose the best service to mail a letter depending on where it was going to go. It's really not all that unlike decisions we might make for packages. Do we sent it via the US Postal Service, UPS, Fedex or Speedy Delivery? There are reasons for each.

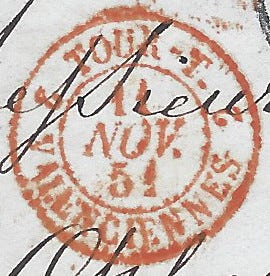

The folded letter shown above was mailed in Hamburg at the Thurn and Taxis office in 1851. If you look closely at the black, circular marking that says "Hamburg," the bottom lettering reads "Th & T." If you look at the red circular marking you will see "Tour - T." Both of these indicate that the Thurn and Taxis postal system was employed to get the mail from Hamburg to France.

The letter passed through Belgium on its rail system and entered France at Valenciennes. It was then taken to its destination in Paris. Once there, the French postal service required 12 decimes in postage (yes, that black ink scrawl is a "12") so the business Fould, Fould & Oppenheim could read their mail. This was based on the mail rate of 60 centimes per 7.5 grams effective from Aug 1, 1849 to Mar 31, 1862

That means this was a heavier letter that required a double rate of postage. It weighed more than 7.5 grams and no more than 15 grams. As a quick reminder, a decime is ten centimes. It would be like a person in the United States telling you that you owe them five dimes when you need to pay them 50 cents.

From Hessian Territories to Foreign Destinations

Thurn and Taxis even got into the game of entering postal agreements with other countries. For example, France agreed to a postal convention with Thurn and Taxis in 1847, putting it into effect in 1849. The 1851 letter shown above was mailed under the provisions of that agreement.

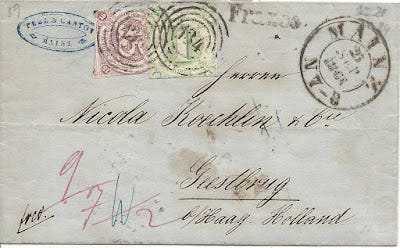

And, here is a stamped letter from Mainz, which was part of Hessen-Darmstadt, a Hessian state in the southern district or kreuzer zone. This letter was mailed in May of 1866 and the two 6 kreuzer stamps paid the required 12 kreuzer rate for a letter weighing no more than 10 grams (effective Apr 1, 1862 until Jun 30, 1867). According to the postal agreement, the 12 kreuzer were split evenly with France. Six kreuzer were kept by the Thurn and Taxis post and 6 kreuzer were passed on to the French post office.

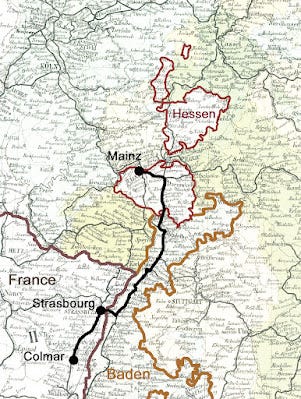

The route of this letter is shown in the map below:

The map illustrates the approximated borders of the Hessian states we have been referencing. The northern district states are part of the cluster with the label "Hessen." The southern district portion is the dark reddish-brown bordered area with Mainz in the northwest.

This letter traveled from Mainz, which is located on the banks of the Rhine River and went by train into Baden, another German state at this time. The letter then entered France at Strasbourg on its way to Colmar.

At the time this letter was mailed, Mainz was considered, by the Germans, as a critical defensive position to protect against French aggression. Napoleon's conquests were not all that long ago (early 1800s) and it probably did not help change perceptions any with Napoleon III (Napoleon I's nephew) holding the position of Emperor for France during the 1860s.

And, speaking of Mainz - here is a folded letter mailed in September of 1861 to le Haag (the Hague) in Holland.

Unlike the previous letter to France, the Thurn and Taxis post did NOT have a specific agreement with the Netherlands. Instead, they used their membership in the GAPU to take advantage of the agreement the collective membership had with Holland, effective April 1, 1851 and ending December 31, 1863.

Like the internal mail, this agreement incorporated both weight AND distance into figuring out the postage required to send a letter between the two entities. The agreement divided the GAPU area into three parts, with the region closest to the Netherlands having the least expensive postage and the areas further from the shared border paying more. It also divided the Netherlands into two parts. Each of these regions are typically referred to as a "rayon."

GAPU rayons:

up to 10 meilen - 1 sgr or 3 kr

over 10, up to 20 - 2 sgr or 6 kr

over 20 meilen - 3 sgr or 9 kr

Mainz was over 20 meilen from the border, so that cost 9 kreuzer in postage.

Netherlands rayons:

up to 10 meilen from the border - 1 silbergroschen OR 4 kreuzer

over 10 meilen - 2 sgr or 7 kr

The Hague was over 10 meilen from the border, so that cost 7 kreuzer in postage.

When we add these two costs together it brings us to 16 kreuzer due to send a letter from Mainz to the Hague in 1861.

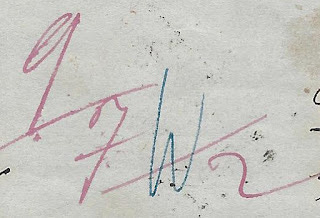

You can actually see the calculation by the Thurn and Taxis postal clerk at the bottom left in red ink.

9 / 7 / 2 in red, W in blue

The "2" in red is the equivalent 2 silbergroschen to be paid to the Netherlands for their share of the postage. Remember, the southern districts worked in kreuzers and the northern in silbergroschen. The northern districts bordered with the Netherlands, so they would actually be responsible for getting the proper amount of money to Holland.

The blue "W" was added by a Prussian postal clerk which stood for the word "weiterfranko," which loosely translates to "continue franking." In other words, "forward this amount of postage" to the next postal service. It was a way to clearly indicate that they were responsible for getting the 2 sgr to the Dutch post. And... if you should happen to care, this was equivalent to ten Dutch cents.

Now, what was I saying about all of the different monetary systems? The good news is this - you do NOT have to remember this. There is no test. If there were, I'd let you do it with open notes. Just read the blog again and fill in the answers!

And a Little Thurn & Taxis Background

How do you summarize centuries of history being the dominant courier service in Europe? I don't really know, so I'll just give you a few highlights and you can opt to learn more if you are so inclined!

At the point I enter the picture with my interest in mail during the 1850s to 1870s, Thurn and Taxis mail is primarily confined to the German area. However, prior to the 1800s, you can find them handling mails from Spain to the Netherlands and Hungary and on down to Italy as an imperial service. Even in the mid 1800s, they had a presence in Iceland and Greenland.

This site, provides an excellent summary of the extent and success of these postal services during the 1700s and I quote it below:

By the end of the 18th century, Thurn and Taxis employed around 20,000 people throughout Europe, including regional representatives, administrative staff and delivery workers. At that time, a letter sent by express mail from Paris to Brussels took only 36 hours to arrive, while standard mail from Brussels to Naples would take 14 days.

To put this into perspective - they did not have trains at that time. That makes these times quite impressive for the delivery of mail.

The earliest iteration of these courier services can be traced back to about 1290 in Italy and it eventually became an endorsed service for the Holy Roman Empire in the late 1400s and Spain in the early 1500s. In the 1800s, after the Napoleonic Wars, the house of Thurn and Taxis became a private service. In 1867, the Prussians purchased the remaining mail services from the princely house, thus ending the Thurn and Taxis postal service.

-----------------------------------------------

Thank you again for joining me for Postal History Sunday! I know I learned several new things in the process of researching the postal history items featured in this post. I hope you enjoyed a break from your world for a short while and maybe you will join me again next week?

Bonus Material

The following text was found in a book titled, "The Industrial Resources, etc of the Southern and Western States, Vol II" by J.D.B. De Bow in 1852. While the book focuses on the United States, it actually gives a contemporary summary of the posts implemented by Thurn and Taxis at the time. The following is from page 352:

In Germany, the first post was established by Roger I, count of Thurn, Taxis and Valsassina, in Tyrol, in the latter part of the 15th century. Subsequently other posts were established in the empire, the most important by counts of the same family; and, in 1543, Leonard of Taxis was appointed postmaster-general of the empire...and, finally, in 1615, his descendent, Lamoral, was invested with the imperial post as an imperial fief, with the right of transmission to his posterity.

A regular post went at that time every week form the imperial court, and also from Rome, Venice, etc, to Augsburg and thence to Brussels and back. This imperial post ceased to exist as such when the empire was dismembered [in 1806.]

Since that period, post establishments of different kinds have existed in the various states of Germany. At present, Austria, Prussia, Bavaria, Hanover, Saxony, Baden, Mecklenburg-Schwerin, Holstein-Oldenburg, Holstein-Lauenburg, and Luxemburg, have each their own independent posts ; but the house of Thurn and Taxis still possess, as a fief, confirmed finally by the Congress of Vienna, the posts in Wurtemburg, Hesse-Nassau, the states of the Saxon-Ernestine line, the two Schwarzenbergs, Hohenzollern, Waldeck, Lippe-Detmold, and in the territories of the princes of Reuss.

In other states, the Thurn and Taxis posts, not as a fief, but founded under a regular compact. The whole post establishment of this family is superintended by a postmaster-general at Frankfort-on-the-Main; and it extends over an area of 25,000 miles, containing 3,753,450 inhabitants. It is, in fact, a private monopoly, managed for the benefit of its owner.

I include this here, not to confuse, but to impress upon everyone exactly how complex the divisions of German Europe territories were in the middle of the 19th century. This explains why this area of postal history is both enjoyable if you love a challenge and frustrating if you were looking for simple answers.Thanks again for joining me this Sunday!