Welcome to Postal History Sunday everyone! I’m glad you could make it to this week’s post. It’s time to tie your troubles to the tail of a kite and then let it fly as high as you can get it. Once, they look like a small dot against the background of turbulent clouds, cut the string and let the whole package go.

Then, come back inside, grab a favorite beverage and a snack. Put on the comfy slippers. And maybe learn something new!

Sometimes, as a writer, I need to mix things up a bit so I can keep the content fresh and recharge my own motivation. So, this week, I felt like doing something a little different. I’m going to pick some covers from different points in time and just share them so we can do some comparing and contrasting.

Mail in the 1980s

Let’s start with a fairly modern item (1986) and show everyone what a simple letter in the United States would look like at that time. There is a 22-cent postage stamp that is affixed to the top right which correctly pays the rate for a piece of letter mail weighing no more than one ounce (Feb 17, 1985-Apr 2, 1988).

The envelope is a standard business-sized envelope that measure 4 1/8” tall by 9 1/2” wide. This size of envelope is known as a #10 envelope that was initially called the “Bond size” by Samual Reynor in 1876. Reynor is credited as being the first to identify his products by this numbering system with the smallest (#1) measuring 1 3/8” by 2 3/4”.

Envelopes in the United States were first produced in the 1840s and their use increased significantly during the Civial War in the 1860s. Machines to help with the folding process were introduced in the 1850s and a good machine operator could make 150 envelopes in one hour (not markedly better than those not using the machine).

Speaking of automation, this letter was postmarked by a machine and sorted by a machine. The addition of the ZIP code (Zone Improvement Plan) on July 1, 1963, provided a numerical system to help with sorting. And, by 1965, work was being done with optical scanners to read those ZIP codes. The first machine was used for live mail sorting was put in place on November 30, 1965 in the Detroit post office. It could sort letters that had ZIP Codes on them at rates as high as 36,000 per hour

A Brief Diversion

Now, some people might be wondering why it is that I have an envelope that probably held a student loan payment that was mailed in the 1980s. Well, the key to my interest is in the postage stamp. If you look at the Capitol Building on the stamp at the left, the ink appears to be a solid black or gray black. The building on the stamp at the right is blue-black.

Collectors have named this variety an “Erie-blue” example of this stamp, which is uncommon. The name comes from the fact that most examples of this stamp variety were found in and around Erie, Pennsylvania.

Stamp collectors and postal historians can be pretty odd in that they can obsess over the tiniest details. I am sure there are some of you who are still looking at the two stamps with completely uncomprehending or, at the least, slightly disbelieving looks. But, we do love to find things that are slightly different from the norm.

If you really want to go down a rabbit-hole, the American Plate Number Single Society hosts this page that shows varieties of this single postage stamp. All of these tiny differences - believe it or not - can give us joy.

Or, maybe a headache. It really depends on what you like.

For those who have interest, this article by John Hotchner provides an explanation of how the blue ink got mixed with the black to make the Erie blue examples of this stamp. But the short explanation is quoted below:

The ink is supplied to rollers (with the stamp images) from ink fountains, each of which contains the desired color for printing. The fountains have a vertical arrangement. The fountain for the red ink is at the top, blue ink is in the middle, and black ink is at the bottom … the blue Capitol building and ‘USA 22’ was a result of contamination of the black ink fountain by blue ink from the fountain above it.

There you have it. Stamp collectors took notice of a very slight color change for a commonly used stamp in the 1980s. They thought enough of it to name it “Erie blue.” And it turns out the reason it exists is because some blue from an inking source got into the black ink as the stamp was printed.

Mail in the 1940s

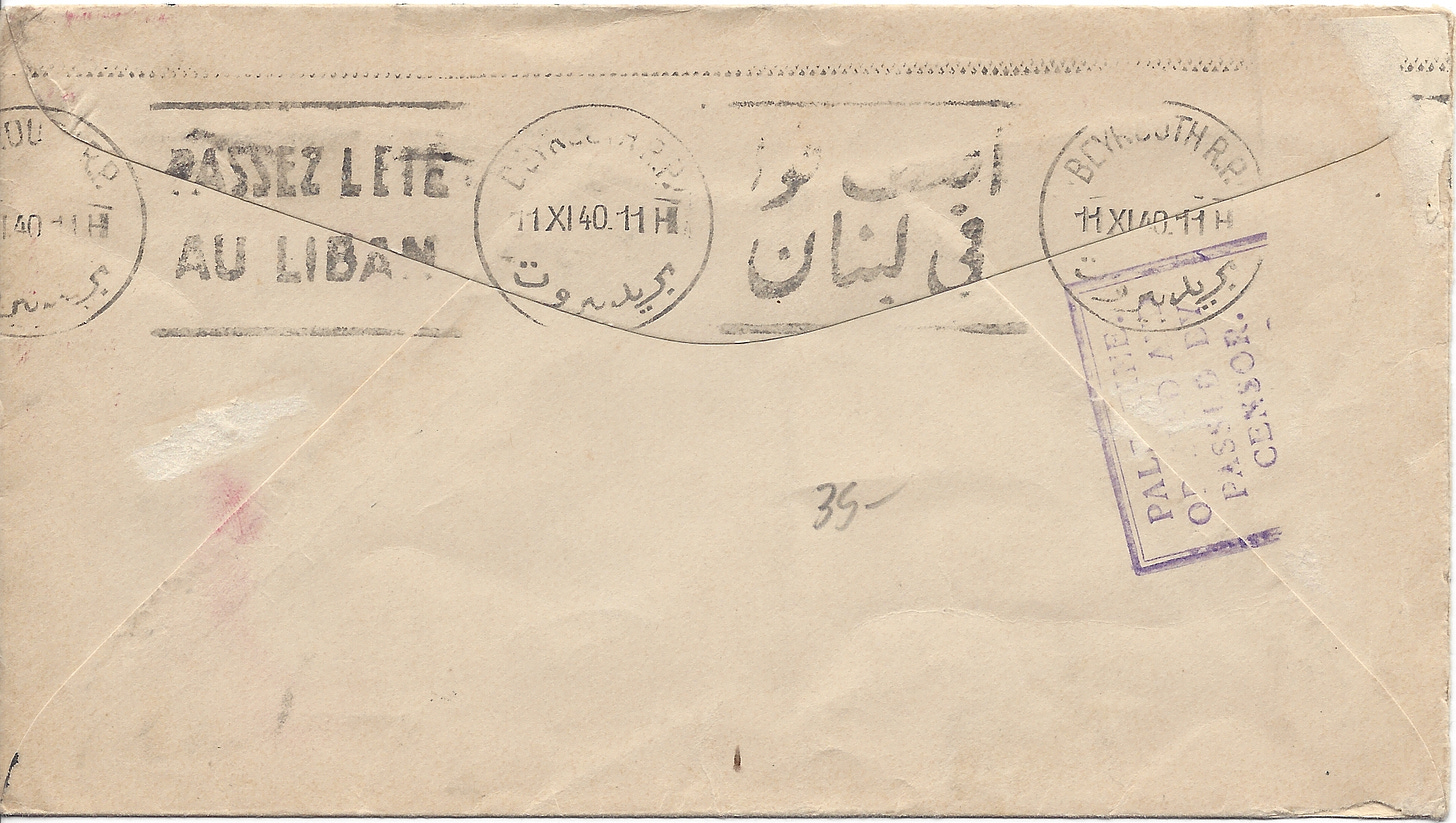

We’re going to take the “time machine” back a little over forty years so we can view this letter that was sent from Plymouth, New Hampshire in the USA to Beirut, Syria. There are 36 cents in postage on this cover paying the composite air mail rate required to get the letter from place to place. A blue label that reads “Par Avion / By Air Mail” tells the post office that air mail service, which was more expensive than “surface mail”, was desired.

However, I am guessing your eyes are attracted to the big, red marking that reads “O.A.T.” in the center.

It wasn’t? Well, it probably is now.

The acronymn stands for Onward Air Transmission or Onward Air Travel (OAT). For those who might like to see an exhibit showing many types of OAT markings, you can take this link.

Some destinations had smaller numbers of letters than were required to fill a mailbag. These were often bundled and kept in an open mailbag. The top letter in the bundle might receive an “OAT” marking to indicate this flexible routing service. The contents of these open mail bags were resorted en route as required and bundles were placed into new (or other) bags for the next section of their journey.

This particular letter was the top letter in what was likely a smaller bundle to Syria. Unlike letters in the 1860s, the mail clerks would not bother to put new postmarks on the covers to track their progress as they went from place to place. As a result, we can only talk about likely routes that this letter might have taken to get from here to there.

An example of the transport routes at the time can be seen on the map shown above. Our letter probably took Foreign Air Mail (FAM) Route 18 to Lisbon and then took “Onward Air Transmission” from that point forward. It could well have traveled via Africa and Cairo to get to its final destination in Syria.

This letter, mailed on September 10, did not reach Beirut until November 11, a significant amount of travel time.

Some of you might also notice the box in purple ink that reads “Palestine Opened and Passed by Censor.” And you might also notice that the right side of the envelope has had some sort of paper tape removed.

Involvement in World War II was already significant, including fighting in Africa. Tensions were also rising in Iraq and Syria with competing German and English interests in that region.

Censorship of mail was used to both collect intelligence and prevent strategic information from being forwarded to the “wrong persons.” Censors would slit open mail, read (and possibly redact) the content. Once complete, the letter would typically be re-sealed with paper tape and the letter would be marked to show that censors had done their job.

Only then could the letter be delivered to its destination.

Mail in the 1840s

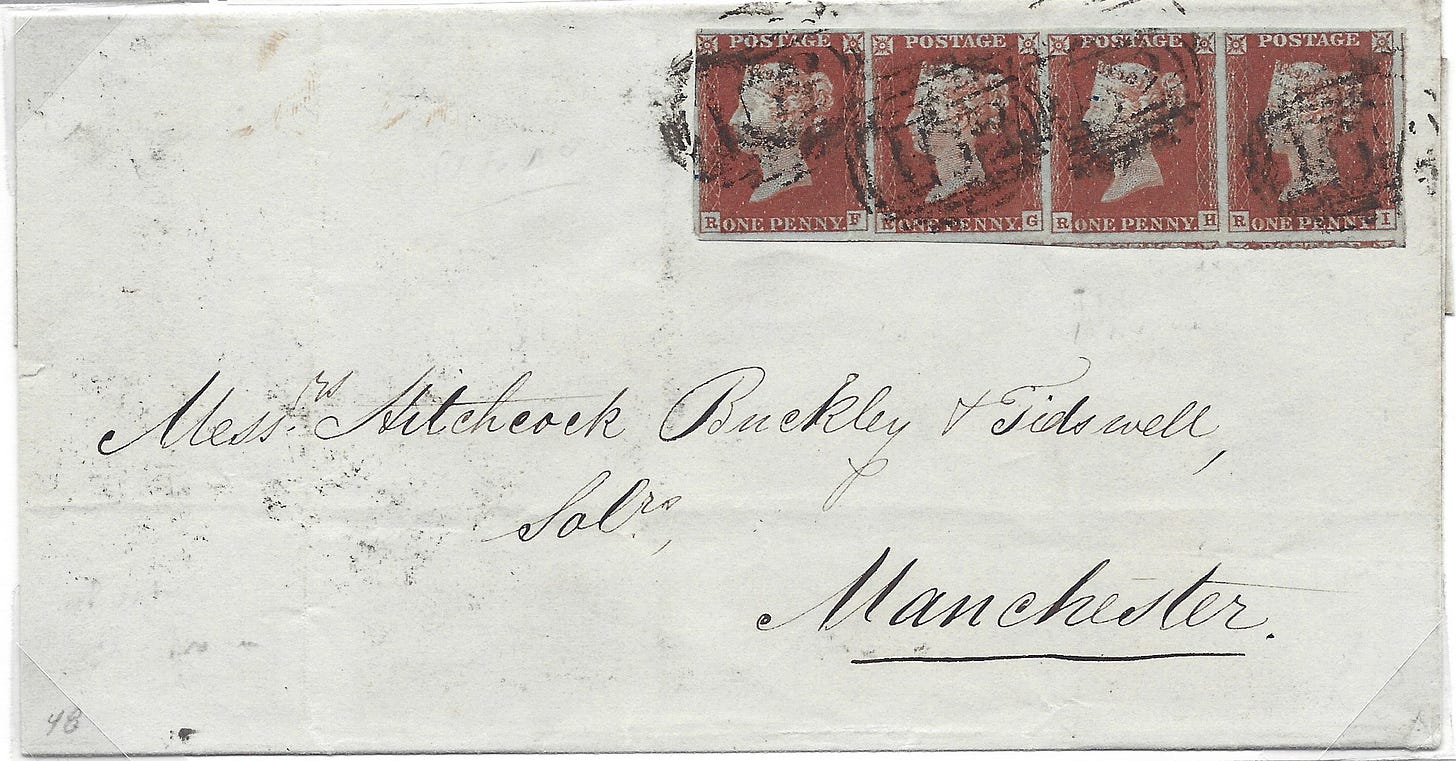

Now I’m going to take a bigger leap back in time, turning the dial almost one hundred years further into the past (1844).

Shown above is a folded letter sent from Burton on Trent to Manchester (both in the United Kingdom). These two locations are only sixty miles apart, which would have been important to calculate the postage required only five years before. The rate structures in the UK included both weight AND distance components until changes in 1840 removed that distance calculation.

The new rate structure was 2 pence per ounce in weight for any distance within the borders of the UK. A special rate for a simple letter weighing less than 1/2 ounce was only 1 penny. So, this envelope must have weighed more than once ounce, but no more than two ounces.

The big innovation in the 1840s for mail services was the creation of the postage stamp to show prepayment. Payment for the mail was frequently left to the recipient prior to this point, which made the delivery process much more complicated. It also introduced the distinct possibility that delivery would be refused and the postal service could be left without compensation for their efforts.

The other interesting thing to note here is that this piece of mail did not use an envelope - unlike all of the other covers shared in today’s Postal History Sunday. Until the mid-1800s, it was common to use an outside cover sheet of paper to contain the contents intended for the recipient.

With the event of cheaper postage, demand for postal services increased. With more people sending letters than ever before, businesses that created stationery proliferated and envelopes became readily available.

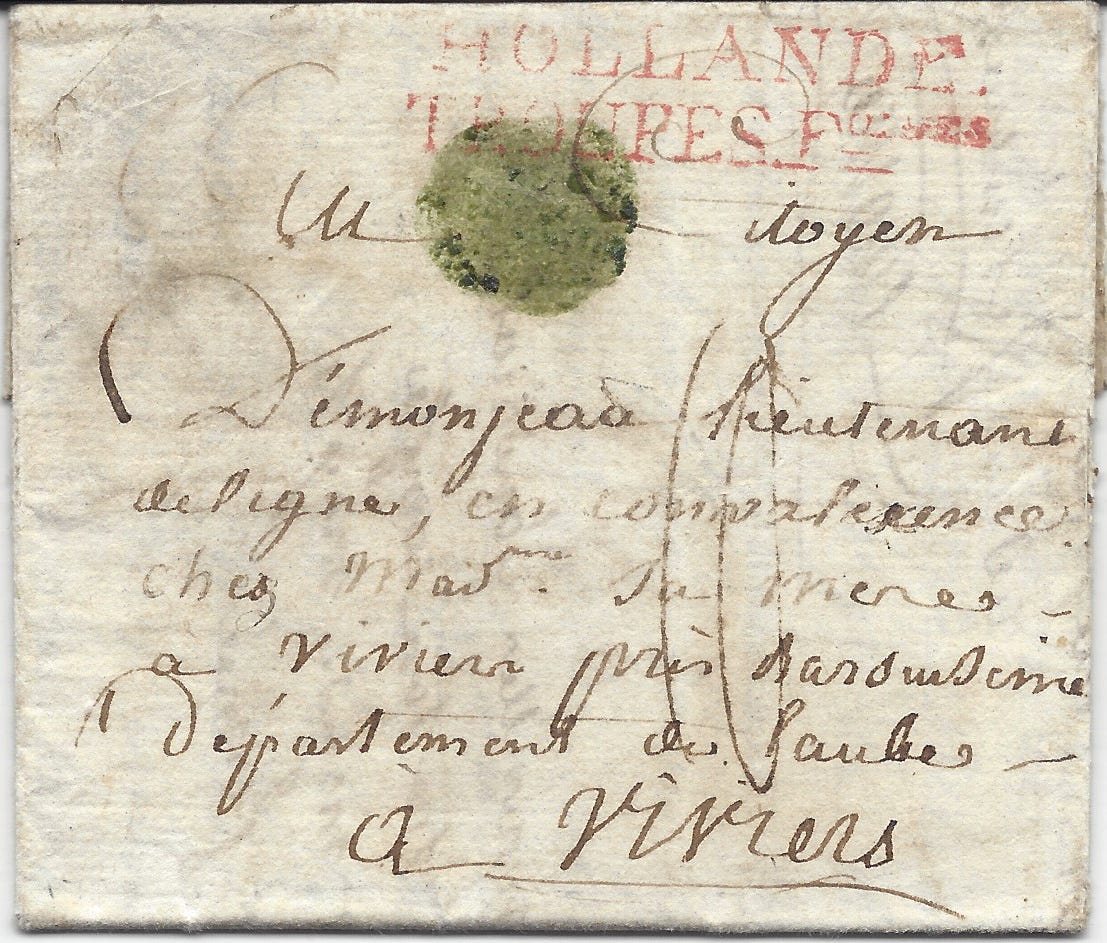

And mail in 1799

Going back another fifty years (almost), I thought I would close with a folded letter that was sent from Utrecht (the Netherlands) to Viviers (France). This time, I’m not going to share many details simply because this one is a work in progress for me.

This was mailed well before the cheap postage movement made inroads and there certainly were no postage stamps available to show payment. Instead, the amount due on delivery was written on the front. The letter appears to be from someone attached to the 8th Army (Batavian) during the Napoleonic Wars.

Another characteristic of note for letters from this period is the quality of the paper. This folded letter uses paper that is thicker than any of the other letters featured today. If you were to touch this paper, you find that it feels “softer” than today’s paper. In fact, you would find a difference between this paper and what you might find in the 1860s. The main difference is that this paper was made with rag stock instead of wood pulp. As a result, it can survive the ravages time more successfully than modern paper will.

I’m going to leave it there so I can save what I discover for a future Postal History Sunday! However, if there are readers who know more about this subject, feel free to send suggestions and guidance! This one will push me further back than I usually go for postal history.

And there you have it - a trip in a time machine! I hope you enjoyed it.

Have a good remainder of your day and a fine week to come.

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack. And, some publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest.

Such a fun and fast postal history read! Thank you!

Best part of my Sunday