We are looking at our first Fall frost at the Genuine Faux Farm, which means we're working a bit of extra time outside to try and get harvests in and things taken care of before that frost hits. That means time to write Postal History Sunday is limited and I will fall back on taking an older PHS (published almost three years ago) and update it this week!

After all, there is no such thing as good writing - but there is good re-writing!

Now, take those troubles and worries and put them in the middle of a book you know has a dull spot in the story line. Yeah, find page 212, don't you always skip over that? This, of course, assumes you are like me and you re-read books you have read before because you don't have time or energy to invest in a new one. If you are the sort to re-read books, you know the rules are different - read the parts you want and skip page 212 if you want.

Now that your troubles are there, you have even more motivation to skip that portion.

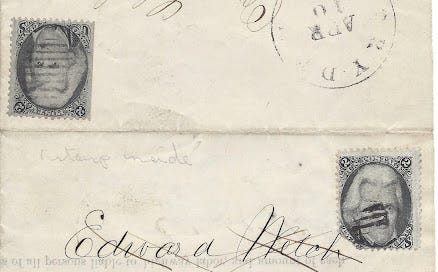

Two addresses, two stamps. Two postmarks?

We'll start this week with an item that was sent in 1865 from Etna, New York to Edward Welsh in Dryden, New York. If you look on the lower half of the folded letter you will see the very light Etna postmark dated April 7, 1865. There is a 2 cent stamp depicting Andrew Jackson that paid the 2 cent postage rate for an unsealed circular.

A circular is a type of printed matter where similar content was sent out to multiple addresses. In other words, it was a type of bulk mailing that qualified for a discounted rate of postage. In order to qualify for the discounted postage, the content had be unsealed (or easily opened) so postal clerks could check to be sure there were no personal messages included with the circular itself that would disqualify the item for the special rate.

In this case, the content is preprinted with the exception of a few details entered by hand that were allowed by the postal regulations at the time. *

*for further discussion - see addendum at end of this blog

The curious thing about the item? Well, there happens to be ANOTHER 2 cent stamp paying the 2 cent circular rate when Mr. Welsh mailed the item back to the Town Clerk at Etna on April 10. To avoid confusion, he crossed out his name and address.

So, what was Mr. Welsh returning to Etna?

This is a signature confirmation form where Mr. Welsh was accepting the position of "Overseer of Highways for District No. 143." Postal laws of the time allowed for such signature confirmations to be an unsealed circular, even though there was additional hand writing on the printed matter. The handwriting only consisted of signatures, a date and a district number. There was no personal message included, which would have disqualified it for the special rate.

Now, if the Town Clerk had written "Hey Ed! How are the wife and kids?" That would have required the letter rate (3 cents) for this item, whether it was unsealed or not. And, if Ed had replied with "Doing just fine thanks!" He would have had to also pay three cents.

What was an Overseer of Highways?

Overseers of highways, whether they were turnpikes or publicly funded roadways, were often farmers who contracted to maintain a section of road near their farm. There would be several such positions for the public roads in any given township. It was not required that they personally had to perform the maintenance. However, having known many farmers in my life, many would scoff at the idea of sub-contracting to someone else.

Early in the history of the United States, roads were largely created by the towns, cities and, sometimes, states, as public works. In New York, eligible men were required to do roadwork three days of the year. If that didn’t sound like an attractive task, they could pay to get out of doing it.

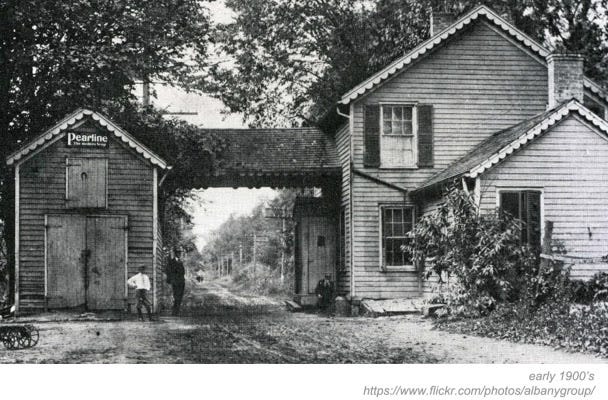

In the late 1700s and early 1800s private enterprise was a big driver for road development. Turnpikes, or toll roads, were often developed with investments by local businesses and community members. These investments were handled by a private company that would use the funding to build the road. Once the road was open, the company collected tolls that would pay for their oversight and maintenance.

When this circular was sent out (1865), the development and upkeep of turnpikes were on the decline. Many toll roads, like the Great Western Turnpike, were losing money with the development of railroads and canals that provided better services (and received more government support). In many cases, including the Great Western, the road was passed back to the public domain - to be maintained once again by state and local governments.

Toll roads were not always popular with the general pubic. There was certainly some push-back from local citizens who were not fond of the idea of paying tolls. Some who lived in the area of a turnpike would use alternative routes to avoid the toll road. These routes were often referred to as "shunpikes." I realize you probably didn't need to know this, but isn't your life just that much richer for knowing it?

If we bring this back to our piece of postal history, there were a couple of attempts to build turnpikes through Dryden. One in 1836 (the Norwich and Ithaca Turnpike) and another in 1816 (the Homer and Genoa Turnpike). It is unclear to me if either were completed or active to Etna, nor is it clear to me if they were still active in the area in 1865.

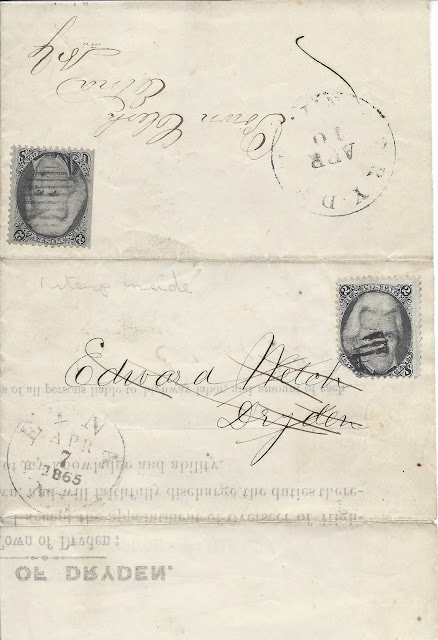

The concept of a "turned" cover

Each of the items I am showing today are examples of what a postal historian would call a "turned cover." The concept is pretty simple. An item was mailed and delivered with an initial address and then the same letter or envelope was modified (usually turned inside out) to allow for it to be sent on to a different address.

What we see next is actually an envelope that was unsealed completely and then refolded and re-glued. The original postal address and stamp were on the INSIDE of the envelope and the second use was on the outside. An astute collector noticed this and slit the sides open so a person could easily see each side.

This envelope clearly started out as another unsealed circular (2 cent rate) mailed from Trenton, New Jersey, on May 22, 1868 and received the next day at Brandon, Vermont. The printed corner card (that's the red ink printing at the upper right) is for John A. Roebling in Trenton. John A Roebling & Sons made wire rope which could be used as part of the construction of suspension bridges among other things. This company made the cables for the George Washington Bridge connecting New York and New Jersey and the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco.

The docketing (sideways handwriting on this cover) may pertain to some sort of business dealing by the addressee E.D. Selden of Brandon, but I cannot be certain.

Selden must not have been a wasteful sort, because when they needed an envelope, they deconstructed this one and essentially folded it inside out, re-gluing it and remailing it with a 3 cent stamp for the letter rate. It was sent on to M.F. Blake Esq. of South Barton, Vermont. The "Esq." often indicated that the addressee advertised that they were in the legal profession in the US.

According to the History of Rutland County, Vermont, Vol 1, E.D. Selden had been the owner of the Selden Quarry (1849-1864). But, I cannot be sure if this was E.D. Selden after they sold the quarry or if this is one of Selden's offspring with the same initials.

Turned covers aren't always neatly opened

Not every piece of postal history comes out of the process of doing its job (carrying the mail) unscathed! How often have you opened mail, only to leave it a mangled, unsightly mess? After all, you aren't thinking that someone might like to collect that useless envelope in the future, right?

Okay. If you are a postal historian, you might think that. But most of us do not.

Now, imagine that the envelope served its duty by carrying mail once, was deconstructed, folded inside out, reconstructed and mailed again - only to have someone indelicately open it that second time around! That envelope might look a bit like this one does:

Here we have another unsealed circular mailed from an unknown location to Front Royal, Virginia. The year is likely after the Civil War and I would place it between 1866 and 1869. The envelope was repurposed and mailed by Thomas W Ashby, Esq at the 3 cent letter rate, being sent from Front Royal to Pattonsburg (VA). There is likely enough information here to learn more about the correspondents, but that will be for another day.

Paper scarcity and paper in transition

One of the themes you might notice here is that the first mailing of a re-used (or turned) item was typically a printed matter item (an unsealed circular). A printed matter item was typically mass-produced and several were sent out at one time to various addresses, accounting for the discounted postage rates enjoyed.

And, yes, in case you were wondering - this is what we often refer to as "junk mail."

So, suppose you are Mrs. Eleanor Boles of Mooreland, Ohio, and you receive this nice, big envelope from some company mailing a circular to you advertising their wares. You might not be interested in what they have to offer, but you can certainly use that nice, big envelope!

In fact, you could mail something that was a bit heavier! Something that weighed over a half ounce and no more than one ounce. All you need to do is turn the envelope inside out and put six cents of postage on there to send it to Mr. Andrew Daig in Rochester, Pennsylvania.

Hey! Stationery was not something everyone could afford or was willing to spend money on. It only made sense to make do with what you had on hand! And if a company was going to send you junk mail with a functional envelope, it makes sense to put for the effort to use it a second time.

The shortage of paper in the Southern states during the Civil War is well-known and often written about. In fact, there are numerous examples of envelopes being made out of wall paper in the South at that time. These, and turned covers, are often referred to as "adversity covers" in that context.

But, there was even more at play here. Up until this point, most paper was made of ragstock (cloth), which was a bit more expensive and becoming harder to come by. On the other hand, the mid 1800s shows the rapid growth of the paper industry that used wood pulp as the basis for paper (the first machine credited to be able to do this was developed in 1844).

At the same time, postage rates were being decreased by many nations to support the use of postal services by the general public. In the United States, the event of the Civil War found more people desperate to communicate with loved ones separated by conflict. The demand for paper and envelopes for mail was increasing.

When you add in the normal shortages that happen during a conflict, it should not be surprising to us that evidence of paper reuse is more common. Whether it was for the purpose of scrimping and saving or lack of access, we will never know - but we still get two stories for the price of one when we find a turned cover!

More resources

If you would like to read a bit more about the history of paper in the United States, I found this article:

Roger Mellen (2015) The Press, Paper Shortages, and Revolution in Early America, Media History, 21:1, 23-41, DOI: 10.1080/13688804.2014.983058

*Addendum

I did promise, way back towards the beginning of this entry, that I would give more explanation regarding the postal regulations for circulars - so here we go!

The United States Postal Act of 1863 (March 3 - effective April 1), set several new regulations for the carriage of mail in the United States. Among them was the new definition of mailable matter and third-class mail. One sub-class of third-class mail was the "transient circular." These were pre-printed mailings that were not regularly scheduled as a newspaper or other subscribed material might be. The rate was 2 cents for up to three circulars to the same address.

Section 24 of this act reads:

Mailable matter, wholly or partly in writing, or so marked as to convey further information than is conveyed in the original print, in case of printed matter, or sent in violation of the law ... shall be subject to letter postage.

In other words, an item would qualify for the reduced postage rates for printed matter UNLESS additional writing was included that extended the original message.

So, a penciled note in the margin that said, "Doing well at the farm, Martha fell into a well yesterday though," would result in the requirement for letter-rate postage. On the other hand, the pre-printed form shown with the first turned cover was allowed because only specific filled in details (date, district number and signatures) were included. All writing was to fulfill the function of the form and no additional messaging was applied.

On the other hand, I am pretty certain that if someone returned a commercial order form with their order filled in, it would require letter postage. All in all, it was part of the evolving interpretation by postmasters for what met requirements and what did not.

Thank you again for joining me for Postal History Sunday. Have a great remainder of your day and a fine week to come.

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack. And, some publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest.