Twenty-Four : Postal History Sunday

Welcome to this week's Postal History Sunday, featured every Sunday (imagine that!), on the Genuine Faux Farm blog and the GFF Postal History blog. This will be, much to my astonishment, the 148th entry of this series that I have offered up for public consumption.

As has been the case for each PHS prior to this one, everyone is welcome - whether you know anything about postal history or not. I encourage you to put those troubles and worries into a place where they cannot be found. Grab the fuzzy slippers and a drink and snack of your choice. Always be aware that you should keep edibles and liquids away from the keyboard and the paper collectibles! Let's see if we can all learn something new today while I share something I enjoy.

I've mentioned it in many Postal History Sundays, but I seem to have this thing for postal history that have 24-cent postage stamps on them. The 24-cent design that features George Washington that was first issued in 1861 has given me the opportunity to explore the workings of the post, especially for mail that left the United States for other countries during a very interesting period of history.

I have even gone so far as to create a physical exhibit (display) that has competed in philatelic exhibitions and done quite well at them. Recently, I decided to undertake the process of making some modifications to that exhibit, which means the topic is very much on my mind.

Why a 24-cent stamp in 1861?

The primary purpose of this particular denomination of postage stamp (24 cents) was to pay the simple letter mail rate between the United States and the United Kingdom (England, Ireland, Scotland, Wales, and the Channel Islands). This particular design was issued in 1861 and the earliest documented use is August 20th of that year. These stamps continued to be produced until early 1869, when they were replaced by a new design.

The 24 cent postal rate between the US and the UK was effective from February 1849 until December of 1867. So, it would make sense that there might have been other designs for a 24 cent stamp before 1861. But, it might surprise you that there was only ONE - and it wasn't issued until 1860.

To the untrained eye, the stamp on the cover shown above may not look all that different. But, if you click on the images of each cover shown above and study them a bit, I think you'll see the changes in design. The new stamp design came about because of the secession of the southern states from the Union. Post offices that now resided in Confederate States still held stock of the old postage stamp designs and there was concern about the potential loss of revenue if no change was made.

Once the new design was released, they demonetized all postage stamp designs that had been issued prior to August of 1861. For those who do not know what it means to demonetize a postage stamp, it simply means they made them invalid to pay postage.

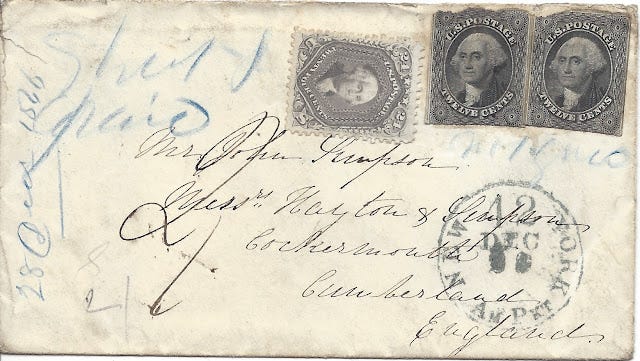

Here is an attempt, in 1866, by a person to use some old 12 cent stamps that were issued in 1851. I think some of us can recognize this scenario. A person found an old envelope that already had the two 12 cent stamps on it or they found the two stamps in a back of a drawer somewhere. They knew the letter they were sending was a bit heavier, so they slapped a newer 24 cent stamp on the envelope and they mailed it, thinking all was well.

The postal clerk recognized that the old 12 cent stamps were demonetized and could no longer be used for postage - so they wrote the words "not good" in blue pencil under those stamps. Then, they wrote "short paid" to indicate that the lone 24 cent stamp, though valid, was not enough to pay for the postage due. As a result, the recipient had to pay the full postage (2 shillings) to receive this letter.

If you are interested, last week's Postal History Sunday discussed how short paid mail was treated as unpaid under the US - UK treaty that was effective at the time. And, if you'd like to learn a bit about how to "read" a cover that was mailed from the US to the UK at the time, this Postal History Sunday will do the trick.

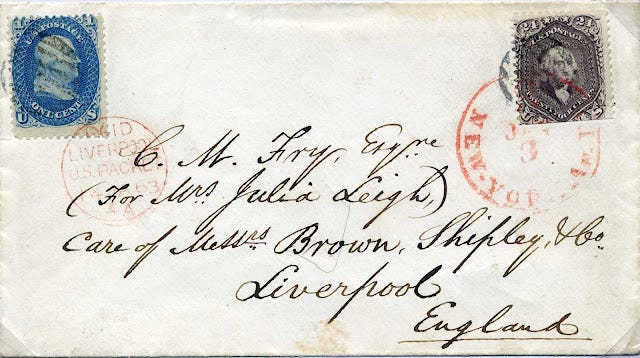

Sometimes the letter didn't start its journey at the post office

A US postage stamp pays for US postal services. But, sometimes, there were travels just to get a piece of mail to a US post office.

The envelope shown above has a 24 cent stamp that pays the cost of mailing the item from New York City to Liverpool. But, the blue 1 cent stamp actually pays for the service of having a New York City postal carrier take this letter to the post office. In the early 1860s, carrier service to and from locations outside of a post office was not all that common. Most people had to go to the post office to mail their letters and pick up any items they expected to receive unless they were willing to pay more for the extra service provided by a mail carrier.

If you would like to learn more about carrier services to the mail at the time, this Postal History Sunday might interest you.

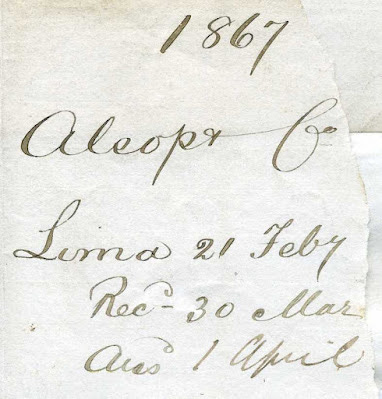

Or maybe a letter actually originated OUTSIDE of the United States, just like this 1867 letter that got its start in Lima, Peru. If you aren't paying attention to this one, you might just assume it is just a letter that went from New York City to London, with the 24 cent stamp paying that postage. But, then you should notice the docket that reads "via New York" at the top left. Once you notice that, you need to ask the question - "where did this letter get its start?"

That's where the docketing on the inside of the folded letter sheet comes in handy. It turns out Alsop and Company had branches of their company in Lima and New York. So, it is likely this item was brought or mailed from Peru with a bundle of other letters that were to be sent on to their eventual destinations from New York.

At the post office

Once we get to a US Post Office, the clerk there would determine the amount of postage required for the item to get from here to there. Sometimes, a letter might already have postage stamps and perhaps other times, the client would purchase the stamps at the point of mailing.

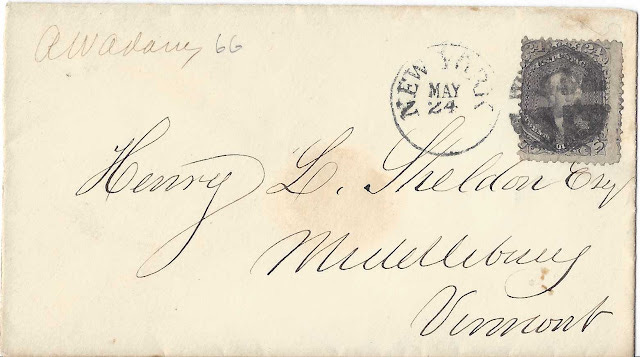

The envelope shown above originated in New York City and was sent to Middlebury, Vermont. The postal rate for letters that did not leave the United States was 3 cents per half ounce in weight (in 1866 when this letter was mailed). The clerk must have weighed this out and found it to be more than 3 1/2 ounces and no more than 4 ounces in weight, requiring 24 cents in postage. The clerk then applied a postmark that included a city-date stamp which was paired with a canceling mark to prevent someone from re-using the postage stamp.

Once the clerk properly marked a piece of mail, it would be placed in a letter bag that would be prepared to take a scheduled mail conveyance - such as a train, coach, or boat.

Leaving the country

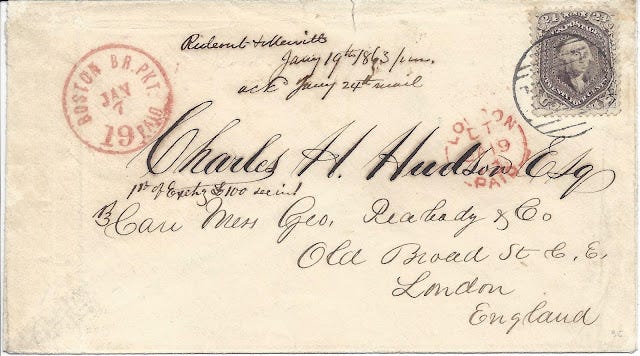

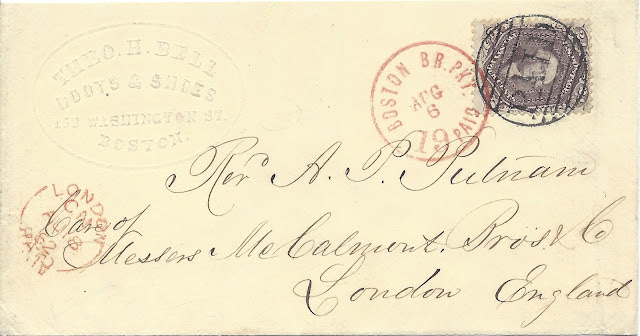

Most pieces of mail bearing a 24 cent postage stamp that still survive today were items that were mailed to destinations outside of the United States. And, most of those crossed the Atlantic Ocean to destinations in Europe.

So, the first order of business was for the US Postal Service to use railroads, coaches, steamboats and other means of conveyance to get the letter to one of the special post offices that had been identified as exchange offices for mail to the destination country.

Shown above is a cover that went to the Chicago exchange office. Other exchange offices at this time for mail to England included New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Detroit and Portland, Maine. And, it was up to the exchange office clerks to place foreign mail into the proper mailbags and get those mailbags to the correct mail packet (steamship) to cross the Atlantic Ocean.

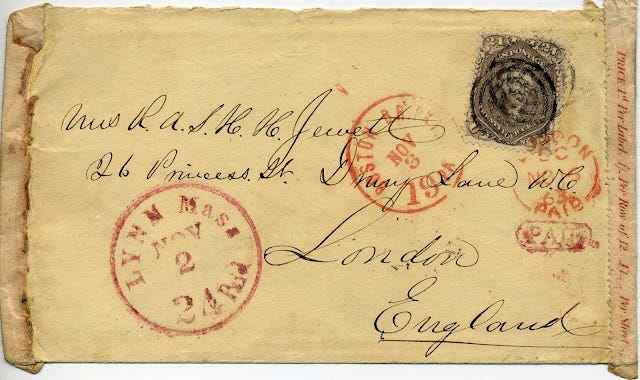

There were several shipping companies that carried mail from the United States. The letter above is an uncommon example of a letter carried by the Galway Line, which was under contract with the British postal service. The ship left Boston on November 3 and made stops at St John's, Newfoundland (Nov 7), Galway, Ireland (Nov 14) and finished the trip at Liverpool (Nov 16). The letter itself was probably off-loaded at Galway and shipped by rail from there to the east side of Ireland, where it would cross the Irish Sea and again go by rail to London.

It can be interesting to try to find letters that traveled by different ships from the various shipping lines. And sometimes, you will find a letter that was on a ship that ran aground or one that had to endure a hurricane.

So, now we're in the United Kingdom

Congratulations! We've made it across the Atlantic and our letter is now in the hands of another postal service. Well, actually, the MAILBAG is in the hands of another postal service. And, that mailbag needs to get to one of the post offices that exchange mail with the United States.

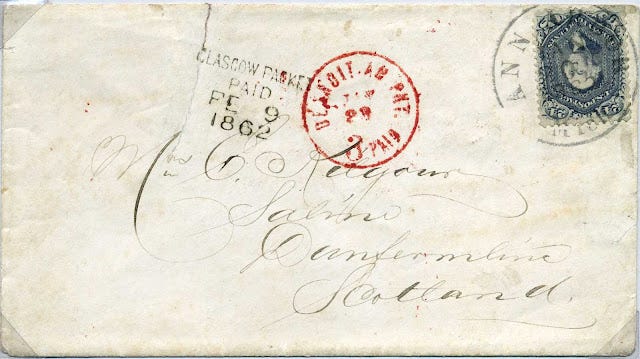

Here's a letter that went to Scotland. The exchange office for the United States was Detroit, where the letter was put into the mailbag. The receiving exchange office was in Glasgow, where the letter was removed from the mailbag. In this case, each exchange office put a marking on the cover that give us clues as to the travels this item took. I suspect most people would not be surprised to learn that the most commonly found exchange office for mails with the UK is London, which is why I wanted to show you something different here! You can find examples of London in the other pieces I show if you are interested.

If a letter was destined for an address in the United Kingdom, it would take the British Mails to their destination. Oh.. look, a London exchange office marking at the bottom left!

It was not all that uncommon for the destination of a letter to be a financial or other institution that would either hold or forward mail for their clients, who were often traveling. This letter was sent care of McCalmont Brothers & Company, a banking firm located in London.

The recipient, B.J. Lang, was a touring musician, sometimes teaching or performing in the UK. We cannot be certain, but it seems fairly likely that the letters might be held at the bank for Lang to pick them up at his convenience. But, it is possible that they were bundled up with other letters and sent to Lang at his current location. It all depended on the agreement the recipient had with the McCalmont Bros - which probably had to do with how much money Lang wanted to spend on such a thing.

This letter is also very interesting because it shows an uncommon example of a "triple weight" letter. Until the middle of 1866, this would have required one more 24 cent stamp.

And beyond...

The British Mail system provided an opportunity for persons in the United States to send mail to other destinations beyond the United Kingdom.

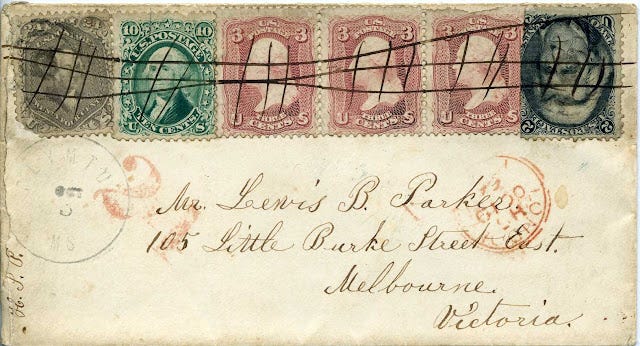

As an example, here is a letter that was destined for Melbourne, Victoria (Australia). The postal agreement between the US and the UK allowed the sender to prepay the postage to the UK AND beyond. With another 21 cents in postage, this letter could get all the way to Australia via the Suez (Egypt).

Or, maybe the destination is the Corisco Mission on the West Coast of Africa? This one required 33 cents in postage to pay for its trip from the United States, to London, and then on by ship to what was once Fernando Po and is now Bioko.

It wasn't just the British mail

Most of the surviving mail pieces that bear a 24 cent postage stamp went to or through the British Mails, but there were certainly other options and other destinations.

And, you knew this was coming! I'm going to give you a "for instance" or two!

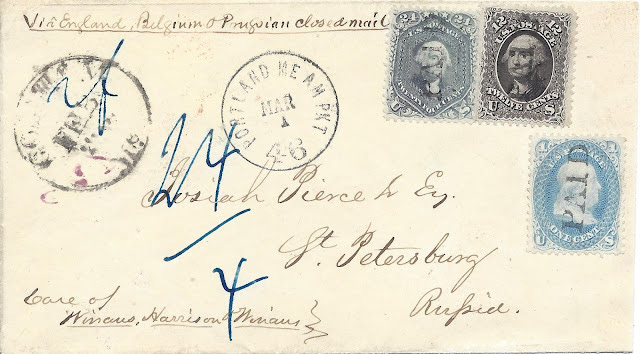

Here is a letter that went via the Prussian Mails so that it could eventually find its way to St Petersburg, Russia.

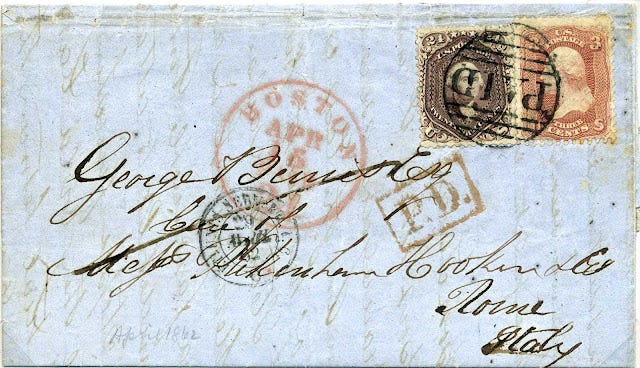

And a folded letter that traveled via the French Mails to Rome, Italy.

The United States had agreements in the 1860s with the British, French, Prussian, Bremen, Hamburg, and Belgian postal services. Later in the 1860s there were also agreements with the Italians and Swiss. The point I am trying to make is that a person can have a great time finding items that show how mail traveled using these different agreements - all using the 24 cent stamp as payment for all or part of the required postage.

The good news? All of this complexity and detail provides me with plenty of fodder for more Postal History Sunday blogs. If you enjoy them, that would be good news. If you don't? Well, I suspect if you don't, you didn't make it this far in today's post!

Thank you for joining me as I share something I truly enjoy. I appreciate your patience and attention as I gave you the "nickel tour" of a subject I have been studying and working on since 1999 (more or less). I hope you learned something new. May you have a fine remainder of your day and a good week to come!

----------------------------------

Hungry for more?

This is the area of postal history where I have the most comfort. So, it makes sense that I have written on items that bear the 24 cent US postage stamp more than any other type of item. If you are a person who wanted a bit more depth, rather than breadth, in this week's post, you have several opportunities to review prior PHS entries that focus on particular aspects of this topic.

I have already linked several Postal History Sunday entries in the prior text, but here are a few more if you want to dig around for a while today!

Costs of Doing Business (letters to Spain)

Puzzling It Out (letter to Chile)

Did Garibaldi Delay the Mail (Italy)

If you do take the time to explore some of the links shared here or earlier in the text, let me know if you have a favorite - or maybe one where you think I could improve it by taking another go at it!

Thanks for joining me. Have a fine remainder of your day and an excellent week to come.