Welcome to Postal History Sunday, featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication.

This is the moment where I (the farmer and postal historian) give myself the opportunity to share some things that interest me with others who may enjoy it. Please take a moment to take off your shoes, put on some fluffy socks and check any baggage you might have from the week at the door.

This week we're going to revisit one of my earlier Postal History Sunday efforts (#11) and re-explore an item that is outside of my normal comfort zone. Postal history covers so much ground that it is not at all difficult to suddenly find that you feel a bit like you are a beginner all over again! The good news is that experience in one area of postal history provides the tools needed to climb the learning curve a bit faster.

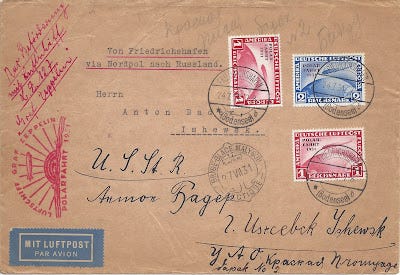

Shown above is a large item that was mailed in 1931 from Germany to Russia - via the North Pole.

By 1931, philately (stamp collecting) had a strong following. In fact, it was not at all uncommon for people to send mail via certain routes or on certain dates to create a commemorative item for some event. For example, each time a new airmail route would open up in the United States, there were individuals who would make up envelopes with special designs to be mailed the first day the route opened. Sure - they paid the postage and they made up a valid envelope or postcard - so these were real pieces of mail, even if the intent was to create a keepsake or collectible item.

An example of philatelic souvenir mail is shown above. William Bilden sent a letter to France... to himself. He overpaid the 30 cent air mail rate with 32 cents in postage because he must have wanted the letter to look a certain way when it was returned to him (he probably liked the idea of this block of four National Parks issue stamps). His goal was for the letter to be taken on a flight (the first flight) via the Foreign Air Mail route 18. And, he met with success because the letter was returned and since that time the letter has passed from his collection to others, and it now resides in mine.

This is an instance where the postal historian sometimes collides with souvenir hunter.

As a postal historian, I prefer to find pieces of mail that carried "real letters" or "real business correspondence" rather than something fabricated as a souvenir for an event (often called an event cover). On the other hand, there are times when the souvenirs themselves illustrate an important event in the history of postal carriage, or they connect so strongly to a historical event that has a good enough story, that I am willing to bend a good bit!

In the 1930s, 'lighter than air' ships were coming into prominence, providing an opportunity to cross the oceans more quickly than ocean-going vessels.

Knowing a good thing when they saw it, many airship flights were promoted to the philatelic community to encourage the sending of commemorative mail for fundraising purposes. Postal administrations all over the globe got into the act by issuing special stamps and establishing special postage rates for these flights (typically costing more than normal mail). And, it worked! Much of the surviving mail items from these flights were made up just to commemorate the event and to provide souvenirs for philatelists and airship enthusiasts alike.

Shown above is a postal card that was clearly created to commemorate a 1929 flight of the Graf Zeppelin. The German 2 Reichsmark postage stamp features an airship over the earth - a design intended to promote the event of airship mail itself. And, the addressee is one A.C. Roe of East Orange, New Jersey - also known as A.C. Roessler. Roessler is well-known for making commemorative mail by addressing items to himself and these letters typically held no correspondence. The goal was acquire a decorated envelope that had traveled at a specific time on a designated route, ship, plane or... airship.

The cover I am highlighting today was taken on a highly publicized flight that was planned to fly to the northern polar regions. Let's remind you now of what that item looks like.

This experimental flight of the Graf Zeppelin LZ 127 was funded to a large extent by philatelic interest (believe it or not), carrying 650 pounds of mail at the time it departed Leningrad and another 270 pounds going the other direction. It is estimated that around 50,000 pieces of philatelic mail were processed through in total.

Given the larger size of this particular envelope, it is possible - and maybe even likely - that it carried some legitimate correspondence in addition to serving as a way to create an event cover. Unfortunately, there are no contents in the envelope, so I can't verify that possibility.

This particular piece of mail cost the sender 4 ReichsMarks (RM), which was roughly equivalent to one US dollar in 1931 (to be more precise 1 $ US was 4.2 RM).

The airship left Friedrichshafen on July 24 and made stops in Berlin (July 24) and Leningrad (July 25). It then transferred its mail to a Russian icebreaker ship on July 27 near Hooker Island. If you look closely, even the stamps had a special marking ("Polar Fahrt 1931" = polar flight) and were sold specifically to persons who wanted souvenir mail to go on this flight.

If the person mailing this just wanted an item to be mailed from Germany to Russia so that it got there as fast as possible, then it would have made sense to take the letter off the airship in Leningrad and let it get to Ishevsk, Russia, from there. But, the typed instruction "via Nordpol nach Russland" made it clear that the sender wanted this item to get off-loaded on the scheduled icebreaker rendezvous.

A commonly sought reward for those who paid to have letters taken on special flights was a hand-stamped design (known as a cachet) that was placed on each letter to verify that it was, indeed, on board the Graf Zeppelin. If you look the other items I have shared thus far, you will find other examples of cachets. The A.C. Roessler card features a blue, round cachet. And, the William Bilden envelope to France has a very large design featuring an airplane and the statue of liberty.

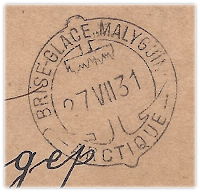

Sometimes, the commemoration was provided by a special postmark - and this event happened to have both a cachet and a postmark. The Russian icebreaker Malyguin met the Graf Zeppelin on July 27 and they processed the mail with the special postmark shown above. The ship took the mail from the airship back to land, where this letter entered the Russian mail system.

This large envelope finally arrived at its destination on August 8, much later than regular mail would have taken - at a much higher cost. But, the recipient had the souvenir they desired - or maybe it was the sender who wanted this envelope for their collection and they prevailed upon a friend to keep it for them? That's something we might not ever know - but it can be fun to speculate.

In order to transfer mail from the Graf Zeppelin to the Malyguin, the airship had to land on the surface of the water. This maneuver was practiced on the Bodensee (Lake Constance), which borders Germany and Switzerland and it was (apparently) successful when it mattered near Hooker Island in Arctic waters.

The build up to the flight and the flight itself was well-publicized and widely followed. The video shown below includes a section, with commentary, on this flight starting at 3:05 on the video's timeline.

For those who would like to learn more about the scientific and mapping purposes of the 1931 polar flight of LZ 127, I suggest this summary on the airships.net site, where the map image shown below was found.

I hope you enjoyed a quick voyage to view the North Pole from an airship.