You Owe Me One (or more) - Postal History Sunday

Welcome to Postal History Sunday, featured weekly on the Genuine Faux Farm blog and the GFF Postal History blog. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with this one (the most recent always shows up at the top).

Postal History Sunday started in August of 2020 as a "pandemic project." The intent of this project was to share something I enjoy with others, regardless of their level of knowledge regarding postal history. I am hopeful that, by continuing to write these weekly posts, anyone who feels like stopping by will feel as if they belong and that this is a place where you can learn something new without pressure or judgement. There is no test at the end - only best wishes as you go out and face the rest of the world in your day.

So let's get started with this week's theme: You Owe Me One (or more)

If you were to send a letter or package today, you would typically be required to pay the postage required to get that item to its destination BEFORE it was mailed. We usually show that payment with postage stamps or printed meter strips that illustrate the amount for the postal services to be rendered. But, prepayment of letters and packages was not always the normal procedure - so I thought we could look at a few examples where the postage was not paid in full at the point it was mailed!

Completely unpaid mail

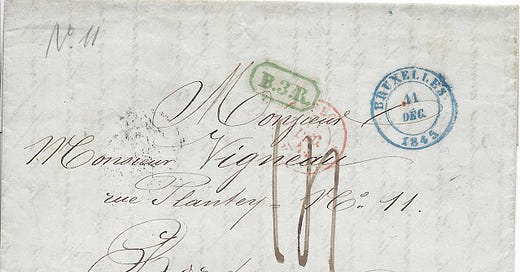

Let's start with a folded letter that was mailed in 1845 from Bruxelles (Brussels), Belgium, to Bordeaux, France. For those who do not know, envelopes were not in common use in the 1840s. Instead, people would designate one sheet to be the "outer sheet" of a correspondence. The sheets would be folded in such a way that the outer sheet would enclose all other sheets and any other contents. With careful folding and the application of a wax seal (or seals), things were secure enough to travel via the postal services of the time.

In the 1840s, the movement for cheap postage was beginning to gain steam with postal services around the world. Reformers suggested that mandatory pre-payment, along with the use of postage stamps, could make the post more accessible to a larger portion of the population while also making postal systems more efficient (and cost effective). So it is during the 1840s and following decades that we can really observe the transition to prepayment.

The letter shown above was treated as mail was typically handled prior to the movement for cheap postage and prepaid mail. Each separate postal service would indicate how much was due for their services and the amount would be totaled up to be collected from the recipient. It was understood that the postal service that collected the money would pass the proper amount back to every other postal system that participated in getting the letter from here to there.

This letter was sent unpaid from Bruxelles and 14 decimes (140 centimes) were due on delivery for the privilege of receiving this letter in Bordeaux, France. The big, bold scrawl that shows up front and center on this letter is actually the number "14." Yes, I know it looks like "1n," but use your imagination a bit and I think you can see how this would be a "14" written by a clerk who did a LOT of this type of writing and was trying not to lift the pen off the paper any more than necessary.

The postage was comprised of two parts:

Belgian postage: 4 decimes

Belgium was separated into three rayons (regions) that represented the distance from the border with France. Brussels was in the third (and furthest from the border) rayon, which required the highest rate of 4 decimes.

Did you notice that "B.3.R" marking? That stands for "Belgium, 3rd Rayon," this was a message that helped the postal people to determine how much needed to be charged of the recipient for Belgium's portion.

French postage: 10 decimes

French domestic rates were based on distance and weight. The distance this letter traveled in France would be from the border with Belgium (Valenciennes) to Bordeaux (nearly 800 km).

The internal French postage rate for each 7.5 grams of weight was established in January of 1828 was 1 franc (100 centimes) for internal mail that traveled 750 to 900 km.

For those who have interest, you can learn a bit about the contents of this letter in this Postal History Sunday entry from October 2020.

Not enough postage - treated as unpaid

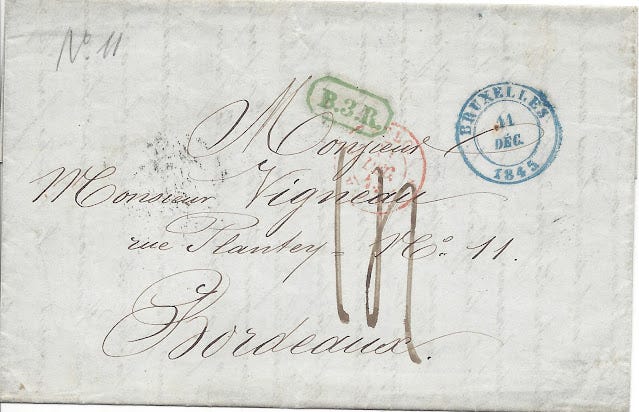

Let's fast forward to the 1860s for our next example. This time around, we do have an envelope, but no contents. This was a heavy piece of letter mail that was mailed from Champlain, New York to Dundee, Scotland. This letter must have weighed more than two ounces and no more than three ounces. So, the postage required to send the letter would have been $1.44.

Unfortunately, the sender applied $1.20, which was not enough. We'll talk about that more in a bit, but let's take a minute and explain how we know these things!

The first clue is the light, double struck postal marking just to the bottom left of the postage stamps that reads "Short Paid." And the second clue is that the New York marking, which has been struck in black ink - an indicator that the postage was not considered to be paid. The other hint is that the word "paid" is NOT part of that marking.

The next clue is the squiggle at the bottom left that tells us that six shillings were due when the letter was delivered to the recipient. Each shilling was equivalent to 24 cents, so six shillings would be equivalent to $1.44. Can you imagine that? The sender put $1.20 in postage on the envelop and NONE of that postage was applied towards the cost of the letter being mailed. Instead, the recipient ended up paying the equivalent of $1.44 just to get the letter.

And, no, there weren't any refunds. Two dollars and sixty-four cents were paid to send this letter - that was a lot of money in 1864.

So, why did this happen?

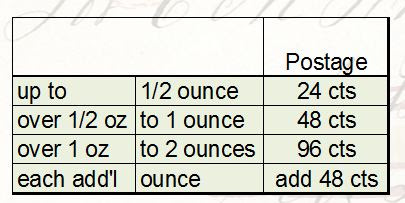

The letter probably weighed more than two ounces and no more than two and a half ounces. The sender wrongly figured that the cost of postage between the United States and the United Kingdom was 24 cents PER half ounce. Instead, the rates between the US and the UK followed the progression in the table below.

The first half ounce was 24 cents, but that was essentially a special discount for light letters. The actual rate was 48 cents per ounce. So, it is very clear that this person made a mistake and did not properly understand the rate structure. The letter was underpaid by twenty-four cents.

So, why didn't they accept the $1.20 and ask for 24 cents (1 shilling)?

Well, Article XXIII of the postal convention negotiated between these two nations stated that "...it shall not be permitted to pay less than the whole rate..." for a letter. The rules by which mail was exchanged between these two postal services simply prevented partial payment. And it didn't matter how close you were to paying it all, nor did it matter how much postage you wasted in the process.

If you would like to know more about how this postal agreement worked, you can go to this Postal History Sunday.

Wait! Don't stop on this topic yet!

I can hear a couple of people's voices asking that I not move on from this particular cover just yet because they noticed this number just under the stamps on the right:

What does this number represent? Any guesses? Oh, right. It's my blog and you're waiting for me to answer....

This "126" stands for $1.26 (or 126 cents), which is the amount of postage the United States expected BACK from the United Kingdom after the United Kingdom collected the postage. The UK was allowed to keep only 18 cents (9 pence) of the six shillings they collected. The rest was returned to the US to pay for their portion of the effort to carry this letter.

The clue is in that New York marking that reads "New York Jun 11 Am Pkt." The "Am Pkt" part tells us that the US was responsible for paying for the cost of carrying the mail on a steamship across the Atlantic Ocean. That cost would have been 32 cents per ounce, which was 96 cents for this particular letter. The US was also entitled to 10 cents per ounce for their mail services to just get to that ship (another 30 cents).

If it helps, this number was not unlike a bill from the US to the UK, reminding them to pay for their agreed upon share of the postage. And no, they still did not care that the sender put $1.20 in postage stamps on the envelope. In the end, that money was essentially a donation to the US postal office - I hope they used it well.

The sender gets some credit for trying

Shown above is an 1868 folded letter from Marseille, France, to Madrid, Spain. The postage stamp shows payment of 80 centimes worth of postage, but the other markings make it clear that that was NOT ENOUGH to get the letter to its destination without a little more coming from the recipient.

A red box with the words "Affranchissement Insuffisant" was applied to indicate that the postage was insufficient to pay for the letter to get to the destination without further payment. The bold, red "30" indicated that 30 cuartos were due at delivery.

The process for short paid mail between France and Spain at the time was to determine the postage by using the rate for UNPAID mail, which was higher than the rate for mail that was prepaid. Once that amount was calculated, credit was given for the amount of postage paid.

The French calculated the weight of postal items using grams and the Spanish by using a unit called adarmes. The weight of this item was greater than 8 adarmes (roughly 14 grams) and was likely no more than 15 grams. The French calculated their postage to Spain with the rate of 40 centimes for each 7.5 grams. But, the Spanish figured their postage rates for each 4 adarmes, which was about 7 grams. This explains why the person mailing this letter thought 80 centimes was enough.

This disparity in weight was bound to make some postal customers quite unhappy - but it sure does provide interest for a postal historian!

The Spanish postage rate for unpaid mail from France to Spain was 18 cuartos for every 4 adarmes in weight.

Triple rate due = 54 cuartos

Less amount paid = 24 cuartos (80 centimes in France)

Total due = 30 cuartos

If you would like to learn more about mail that was partially paid and some credit was given for that payment, this Postal History Sunday from June of this year might be of interest to you.

Where the stamps are placed might matter

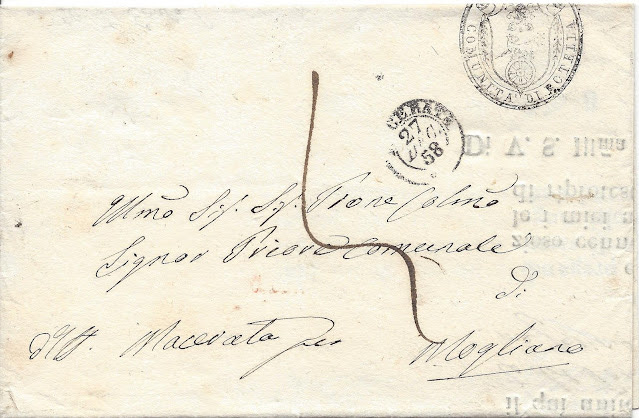

Shown above is folded letter that was sent from Macerata to Mogliano in 1858. At that time, central Italy was controlled by the Catholic Church and I typically refer to them at the Papal States or Roman States.

This cover looks a lot like our first item. There are no stamps visible on the front to show an attempt to prepay the postage. There are no markings that tell us it is paid. And, there is a BIG SQUIGGLE on the front. That usually means the recipient was going to have to pay something if they wanted to read what was in this letter. The big squiggle is actually a "4." Once again, use your imagination and maybe you'll start to see it.

This item required 4 bajocchi in postage to be paid by the recipient. The amount was written on the front. But, the Papal States actually took it one step further, the placed the equivalent amount of postage on the back.

In this case, two stamps, each denominated for 2 bajocchi each were affixed.

If you would like to take a crack at figuring out why this item cost 4 bajocchi, you could view this Postal History Sunday from June. The information you need might be there! Or, you can just be content with picking up this neat little tidbit that the postage stamps on the back corresponded to the amount due. Your call! Certainly no pressure from me.

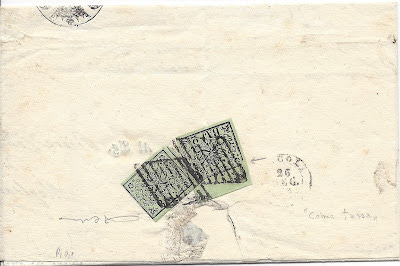

Special postage due stamps show what you owe

The whole issue of mail that was not fully paid eventually led to the production of postage due stamps. These stamps were placed on an envelope that required additional payment to make it clear how much was to be paid and/or to serve as a receipt or evidence of payment. In the case of the Papal States cover before this one, the stamps were not specially made to indicate postage due. They were simply the normal postage stamps issued at the time.

But, this time around, we have a 2 cent stamps that specifically tells us it is for "postage due."

This 1935 letter from Cape Town to Cincinnati, Ohio required an additional 2 cents (US) from the recipient. You can see a New York marking at bottom left that also indicated the amount due. One more marking, right next to the postage due stamp says "T 10 c," which stood for "Tax 10 centimes." Ten French centimes were equivalent to 2 US cents at this time.

Some choices resulted in split payment

This letter was sent from Geneve, Switzerland to Rome in 1868. The postage applied on this cover is 35 centimes and there is a marking that reads "P.P." This tells the Rome post office that postage was only paid to the Papal border. The clerk in Rome scrawled a "20" to alert the carrier that they should collect 20 centesimi from the recipient at delivery to pay for postal services in the Papal territory.

This is a situation where the sender made a choice that had no option to prepay all of the postage. That choice?

Voie de Florence

They opted to send this letter via Florence in the Kingdom of Italy. The Pope refused to recognize the Kingdom of Italy, which meant the Papal postal system was not able to execute a postal convention for mail that went to, from, or through the rest of Italy. Because the Swiss and the Italians had an agreement, a person could pay for that portion of the trip. But, the Papal postal system was going to handle their own postage, thank you very much and they would collect from the recipient (so there!).

The person who mailed this item actually had other routes they could have selected and they could have prepaid the postage via those routes. But, this route was faster, which might have made them and the recipients of this letter quite willing to split the postage.

If you would like to learn more about this, a July Postal History Sunday gives more details.

And some postal clerks went above and beyond

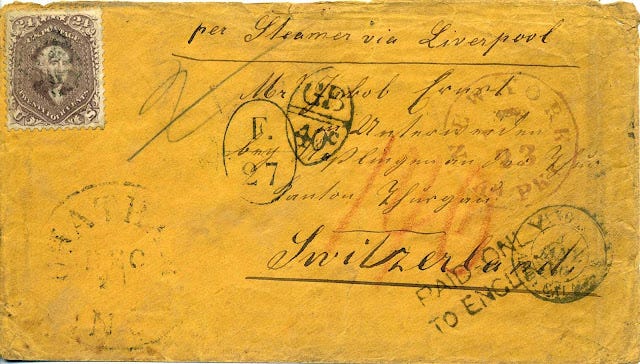

I am actually going to end this week's Postal History Sunday with a teaser by telling you that I will include the story of this envelope mailed from the United States to Switzerland in a future entry.

I know, I know. If I'm going to bother to show it, I should explain it. And I will do so with only the abbreviated version so you can understand why this item is included here. This is another example of an item that had some of the postage paid by the sender and some paid by the recipient. However, this time, it was unintentional!

The sender thought they were paying for the 21 cent rate to Switzerland via France. They placed a 24 cent stamp on the cover and assumed all was well. Unfortunately, the letter was too heavy and would require 42 cents to get to Switzerland. Most of the options for getting this letter to Switzerland would have treated this letter as unpaid because it did not pay enough for the entire amount due... except one.

The postal clerk realized this and they adjusted the letter so that it would go by the "open mail" option provided in the agreement with the British. The letter could be paid as far as England (notice the words "Paid Only to England" at bottom right) and postage to get that letter from England to Switzerland could then be paid by the recipient.

This particular piece of letter mail has enough complexity that it probably deserves its own Postal History Sunday. At least I didn't leave you hanging completely!

There are certainly many other ways that unpaid or short paid has been handled. For example, there are some instances where an additional fee was added to the amount due as a penalty for failure to pay enough. But, what do you expect from a weekly blog? If I manage to tell you everything today, you won't come back next Sunday. Right?

Thank you for joining me this week for Postal History Sunday. It was fun to put these items together and explore some of the ways unpaid and partially paid mail was handled. I hope you learned something new and were entertained at least a little bit.

Have a great remainder of your day and a fine week to come!