Welcome! This week’s entry of Postal History Sunday is ready for you to enjoy. That means it is time to creatively set aside your troubles so you can give yourself a little space to enjoy this week’s exploration.

One of our tricks we use at the farm is to wait for a one of our friendly felines (also known as Farm Supervisors) to take notice of our presence. Then, we set our troubles somewhere as if they are important and should NOT be meddled with by a cat. Soon thereafter, one (or more) of the cats will be sitting in, sleeping on, or playing with whatever it is we’ve said we don’t want them messing with.

I will say this. If you have an indoor cat, wrap those troubles up with some yarn and you’ll never see those worrisome things again.

Unless you clean under the refrigerator.

Speaking of the refrigerator, grab your favorite beverage and a snack. Put on the fuzzy slippers and sink into that comfy chair. It’s time for Postal History Sunday!

This week I decided to borrow the title from an excellent baseball movie because I have been enjoying baseball audio broadcasts on days when the wind and rain have made it difficult to be outside. I think you’ll figure out why I selected “A League of Their Own” for this week’s topic - if only because I can’t keep a secret and will probably just tell you.

Two covers, two postage rates - why?

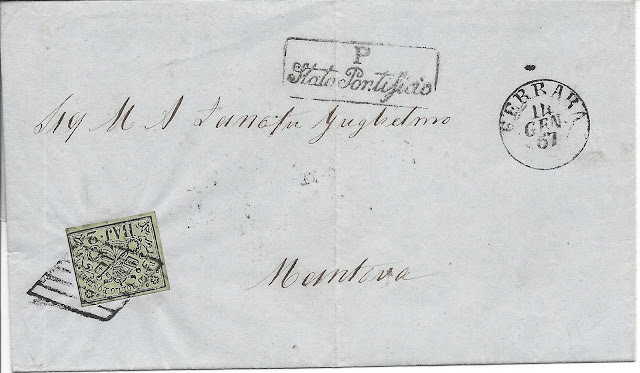

Shown above are two folded letters. Both were mailed from a location within the Papal States (central Italy) to the city of Mantova - then in the Kingdom of Lombardy (northern Italy). Both covers were fully prepaid by the postage stamps placed on them. And they were both simple letters (a letter that required no more than the basic postage level to get to its destination).

So why does one letter have a postage stamp representing 2 bajocchi and the other 5 bajocchi?

The simple answer is that letter mail between the Papal States and the Kingdom of Lombardy was rated by a combination of the weight of a letter and the distance that letter had to travel. The first letter did not have to travel as far as the second because Ferrara is closer to Mantova than Bologna.

Calculating weight & distance based postage

Letter mail from the Papal States to the Kingdom of Lombardy in 1857 was calculated by determining both the weight of the letter and the distance it had to travel. For every 15 denari (17.7 grams), a postage rate would be charged. A simple letter could weigh UP TO 15 denari. But as soon as the letter weighed even a little bit more than that, it would cost two postage rates.

The base postage rates were set by the distance traveled. These distances were measured by the Austrian meilen or lega, which was roughly equivalent to 7.5 km.

Rather than use more words, let me just illustrate how the rates worked with examples.

1. Distances up to 10 Austrian meilen

Above is the folded letter from Ferrara to Mantova. This was considered to be within the shortest distance class for letter mail between the Papal States and Lombardy at the time. Technically, this would be no more than 10 meilen or 75 km. However, if you use a present day online mapping tool, you’ll find that the distance is about 88 km. What matters is how the postal systems classified the distance at that time - and this letter was determined to be in the first distance.

The postage rate for letters leaving the Papal States for the Kingdom of Lombardy and traveling no more than 10 meilen was 2 bajocchi per 15 denari.

This folded letter was mailed in Ferrara on January 14 and received in Mantova (Mantua) on January 15. I think most of us in today’s world would consider that to be excellent service.

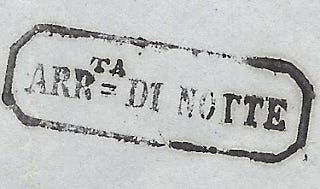

This seems like a good time to remind everyone that the postal organizations of the time were often very sensitive regarding their reputation for timely mail carriage. As a result, we often see postal markings that attempt to explain what might be considered a delay of the mail.

In this case, it was not unusual for something mailed in Ferrara to arrive at Mantova the same day. The Mantova post office actually sent their mail carriers out for multiple deliveries each day, which made it possible for this to happen.

So, believe it or not, people in Mantova might actually have been disappointed if something from their friend or business partner did NOT arrive on the same day. However, this letter must have been sent later in the day on the 14th. As a result, it took a late mail train or coach to get to Mantova, arriving too late for carrier delivery on the 14th. The receiving post office in Mantova made certain to make that entirely clear by handstamping this marking "ARRta DI NOTTE" (arrival at night) on the back.

2. distances over 10 meilen and no more than 20 meilen

Here is a letter that was mailed from Bologna, in the Papal States, on July 9, 1857, to Mantova. This letter arrived on July 10 early enough to be delivered with the first distribution of the mail. This makes it entirely possible (and maybe even likely) that this letter ALSO arrived at night.

However, unlike the first letter, there is no marking stating that this item arrived at night. Why?

One obvious answer is that the train or coach carrying the letter arrived early in the morning on the 10th before the first carriers left the Mantova post office. But even if this item had arrived during the night time hours, it probably would not have been given an “arrival at night” marking. It was perfectly normal for items traveling this longer distance to arrive the next day (and not the same day). So, there was no reason to provide a marking to explain a perceived delay.

The postage rate for this second (or middle) distance was five bajocchi for every 15 denari. Happily, the sender affixed a 5 bajocchi postage stamp on the letter and it was properly, and fully, paid.

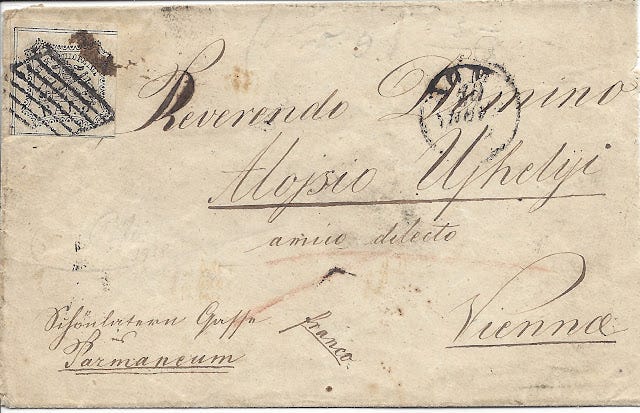

3. distances over 20 meilen

Our last example from the Papal States actually goes to Vienna, Austria. At the time these letters were sent, the Kingdoms of Lombardy & Venetia were actually semi-autonomous states under the control of Austria.

This letter traveled more than 20 meilen (150 km). If we use present-day mapping tools, we find that the distance traveled in this case is actually over 1000 km. The rate for mail for the longest distance was 8 bajocchi per 15 denari.

The Austro-Italian Postal League

As promised, I can’t keep a secret. The “league” I was referencing with this week’s title is the Austro-Italian Postal League.

At the time these letters were sent, the Austrian Empire was under Habsburg control (1804-1867) and encompassed a much broader area than Austria’s current borders. In addition, the Italian states of Modena, Parma and Tuscany were governed by members of the Habsburg line. Thus, there was a keen interest to support efficient lines of communication in the hopes that it would help keep the Habsburgs in power.

While the Kingdoms of Lombardy and Venetia were under Austrian control, Modena, Parma and Tuscany were not. And, unlike the others, the Papal States were governed by the Catholic Church. So, mail between these states and Austrian territory would be classified as foreign mail, which would require some sort of postal convention to set the terms for mail exchange.

The agreement Austria promoted did more than arrange for mail between each of these states and the Austrian Empire - it actually included procedures for mail between each of the participating states as well. Thus making it a league of nations with a common mail exchange agreement.

Tuscany entered into the postal arrangement on April 1, 1851. Parma and Modena joined on June 1 of the following year (1852). And, interestingly enough, the Papal States, not under Habsburg control, also agreed to exchange mail with Austria and these other states under this convention (Oct 1, 1852).

This league, along with the German-Austrian Postal Union, were precursors to the global mail agreement nations use today (the General Postal Union established in 1875 and then the Universal Postal Union active since 1878).

A couple of the interesting aspects of the Austro-Italian Postal League are worth mentioning. First, participants were required to issue postage stamps. If it weren’t for this requirement Modena (for example) would have been able to participate sooner. And second, the postal service that collected the postage kept ALL of the postage.

This was revolutionary at a time when most postal conventions took great pains in outlining how postage was to be split between nations. Strategically, this move was quite clever. By making mail exchange simpler, Austria ensured better communications with northern and central Italy. This made it easier to gather intelligence and, possibly, spread propaganda.

While this was a good idea, the postal league did not halt the movement towards Italian independence. By 1866, most of Italy (including Lombardy & Venetia) was unified under their own government.

There are actually FIVE different monetary units being shown in this table. Three are obvious with the Austrian kreuzer, Papal State’s bajocchi and Tuscan crazie. The centesimi in Lombardy-Venetia actually had a different value than the centesimi in Modena and Parma. Material I have read by a few different Italian postal historians indicate the difference by referring to the Austrian lira (Lombardy-Venetia) and the Italian lira (Parma and Modena).

Since the Austrian Empire was in the position of power, it should not be surprising that the rate structure followed their own internal rate structure. The required postage was determined by a combination of weight and distance traveled. The weight was determined by Austrian loth (effectively 17.5 grams) and the distance was measured by the Austrian meilen (or lega), with each meilen equal to about 7.5 km. In order to make this work, rough equivalents were adopted for local currency, weight units and distance measures.

For example, a loth was equal to 17.5 grams. But, in order to provide the Papal States with an easy weight for postal rate progressions, they accepted 15 denari as equivalent (17.7 grams).

Letters between Italian States

It’s at this time that I can take an opportunity to provide an example of the Austro-Italian Postal League at work between two Italian States. The letter shown above was mailed in 1855 from Modena to Bologna, in the Papal States. The postage paid was 15 centesimi, which was appropriate for letters traveling no more than 10 meilen.

If this cover seems familiar to some of you, it was one of the items featured in Duck, Duck, Grey Duck (PHS #220). At the time I wrote that article, I was not able to determine what the black boxed marking was on this letter. Happily, with some much needed help from Dieter on the German Board, I now have an answer!

Disinfected letters often show evidence of slits or holes that were cut or punctured into the cover to allow the disinfecting agent to reach the contents of the mail. The disinfection postal marking on this letter indicates that it was disinfected by “contact,” thus no slits or punctures were made on the cover.

There were a couple of options when it came to disinfecting letters by “contact.” Items could be wet down with a disinfecting agent or they could be exposed to fumes. I cannot tell you which method was used on this particular cover.

The disinfection oven shown above was used to expose the contents of the cage to sulpherous fumes. The long iron tongs, shown in front of the cage, were used to place letters inside. The handle on the right could be used to turn the cage in an effort to evenly expose the surfaces of the lettres to the fumes. I assume the tongs were also used to remove the letters once the treatment was completed. The Fondazion ProPosta in Rome provides additional information on this page edited by Paolo Marcarelli for those who have interest (in Italian).

Another incomplete piece of business mentioned in Duck, Duck, Grey Duck is the use of the words “via Malcontenti” at the bottom left of this cover.

In my prior writing about this cover, I shared my discovery that “via Malcontenti” was, essentially, part of the address for the recipient of this letter. I did not realize at the time that “Via” is equivalent to “Street.” My mind was stuck on letter routing dockets that I often find on trans-Atlantic mail between the US and Europe.

Well, now I have located the actual street on an 1835 map of Bologna. Via Malcontenti was named for a family that lived there as late as 1660. The street was still there 175 years later, even if the family was not.

It is tempting to think that the completion of a Postal History Sunday article closes the book on learning. But I am finding that I have many questions remaining after each one. As it stands, there are so many open questions that I sometimes fear I will forget to seek the answers for some very interesting queries. This time, I was fortunate. I remembered the questions AND I found new resources to help me with the answers!

Thanks for joining me for Postal History Sunday. Have a good remainder of your day and a great week to come.

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack. And, some publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest.

Quite the disinfecting device!

Makes me wonder how many letters were "Losto en la fire-o"! 😁