The weekly cycle continues and I’ve got yet another article where I share something I enjoy with anyone who might have interest. But, first, a little bit of housekeeping!

I have noticed that subscribers continue to trickle in, which reminds me that it is important to welcome all newcomers. Everyone is welcome here! It doesn’t matter if you are an expert in postal history or if you are just idly curious. I try to write in a way that is accessible and (possibly) entertaining for everyone. It is my hope that we can all learn something new in the process.

Some of you might have noticed that I actually have two Substack publications - and if you didn’t - you do now. This one is dedicated to the postal history topic. The other, Genuine Faux Farm, includes everything else. If you want a sample, here are three writings from the GFF Substack that have received very positive feedback (one, two, and three).

And now, keeping with tradition in this space, it is time for you to put those troubles away for a short while. Grab your favorite beverage and maybe a snack - but keep the crumbs and liquid away from your keyboard! Put on the fuzzy slippers and settle into your favorite reading space.

It’s time for Postal History Sunday!

A hobbyist’s goals

We all have our hobbies - at least I hope we all do. Some like to see and identify wild birds. Others ride on snowmobiles. A few others like to yell at the television or whatever device they use to view sports or the news.

With those hobbies there are often goals. For example, Tammy, my partner, set a goal to go kayaking each month of 2024 - which she achieved. Since we live in Iowa and water freezes in the colder weather, this is an accomplishment.

As a philatelist (stamp collector) and postal historian, I also have some goals I hope to achieve. Some have their roots in the days when my interest in this area was first being formed. There were images of several stamps I viewed in catalogues that I hoped to see in person one day.

Two weeks ago, I shared one of those items. And this week, I share another.

On July 1, 1847, the United States Post Office issued their first postage stamps. They came in two denominations that reflected the postage rates that had gone into effect two years prior. The cost to mail a letter was five cents per half ounce if that item had to travel no more than 300 miles. For longer distances, the cost was ten cents.

This issue would be valid for postage for only four years when letter rates were reduced. On July 1, 1851, these stamps were demonetized and could no longer be used to pay postage costs.

The funny thing about “firsts” is that they attract attention, especially after it is clear that they were the first of many. The US Post Office has issued thousands of postage stamp designs over the years, so this issue certainly qualifies. About 3.6 million copies of the five cent stamp were printed. While only a tiny fraction of them survive, there is still planty for specialists to study. And, at the same time, most collectors can find an available example if they want it.

But it still requires a certain investment to get a fairly average example. When every collector wants at least one example, it tends to keep prices a bit higher than say, the 1032nd postage stamp issued...

Once again, I was able to fulfill my own dream when some of the people who had specialized in this issue decided the time had come to let their collections go. When the supply is much higher than normal, the cost usually comes down and a person like me can try to land one.

Express Mail that wasn’t

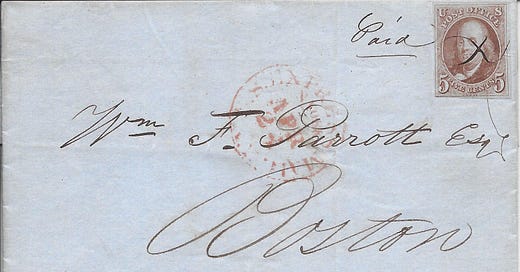

The letter I featured at the beginning of the article is a short, folded, business letter sent from New York City to Boston on April 24, 1850. The distance between Boston and New York City certainly qualifies for the under 300 mile postage rate and the five cent stamp paid the postage for a simple letter.

Other than the pen marking on the postage stamp (a cancellation to prevent reuse of the stamp), the only other postal marking on the cover is shown above. That marking tells us that the letter was carried by “U.S. Express Mail” from New York.

Express Mail certainly sounds special and … well … fast. And that is certainly what customers were supposed to think. The reality was that there really wasn’t anything “special” going on here as far as delivery service was concerned. If that were the case, people would have expected to pay additional costs. Examples of these sorts of express services would be the Express Mail to the southern states in the 1830s or the Pony Express in the 1860s.

Actually, when I say there was “nothing special” going on here, I’m not being entirely truthful. This express mail postmark tells us that the letter was dropped in a letter box at the pier before the ship’s departure. Some of you might remember that the opportunity to get a letter onto a ship just prior to its departure could cost a premium. But, it did not in this case. If you were willing to drop it off at the pier, regular postage costs would be sufficient.

This particular marking was applied by a route agent on the steamship that carried this letter on the first leg of its voyage. The “express mail service” between Boston and New York City had its start in 1842 (and would terminate in 1857), before laws were passed that made it impossible for private mail companies to continue with their express services. The express mail was taken by the most efficient route between the two cities and trips were scheduled for every day except Sunday.

So, there is also some truth in advertising here. This letter was going by the most efficient route and probably couldn’t get there any faster by any other method. But, once again, there wasn’t any special service here. Letters between New York and Boston could have traveled this route without having been dropped at the box at the pier. But it didn’t hurt to use the word “express” to indicate that the US Post Office could get mail from point A to point B every bit as fast as the private express companies could.

Deciphering how it got from here to there

I have become quite adept at figuring out how letters crossed the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans in the 1850s through 1870s, but I have not spent much time worrying about the routes letters took inside the United States. However, since the featured piece of postal history came from the collection of Hugh Feldmann, it seemed like taking the time to do that would be a good way to honor him.

Hugh is known for producing two reference publications, US Contract Mail Routes by Water (1824 - 1875) and US Contract Mail Routes by Railroad (1832 - 1875). These represent a tremendous effort to go through Post Office records to determine who held the contracts to carry the mail via the existing mail routes of the time.

The US Post Office, rather than develop and maintain an independent transportation system, contracted with private companies - such as railroad and steamboat lines - to carry the mail. As you might guess, given the fact that mail needed to get from any point in the country to any other point in the country, there were many such contracts. And these contracts were negotiated for four-year periods.

Using Hugh’s books, I was able to trace the route this letter took. Then, I was able to find a newspaper clipping (shown above) advertising the steamboat service from Pier 18 across from Courtlandt Street.

At this point, it makes sense to summarize what I know about this folded letter.

The contents of the letter are datelined “New York, 24th April 1850”

The letter was placed in the drop box on Pier 18 on Wednesday, April 24

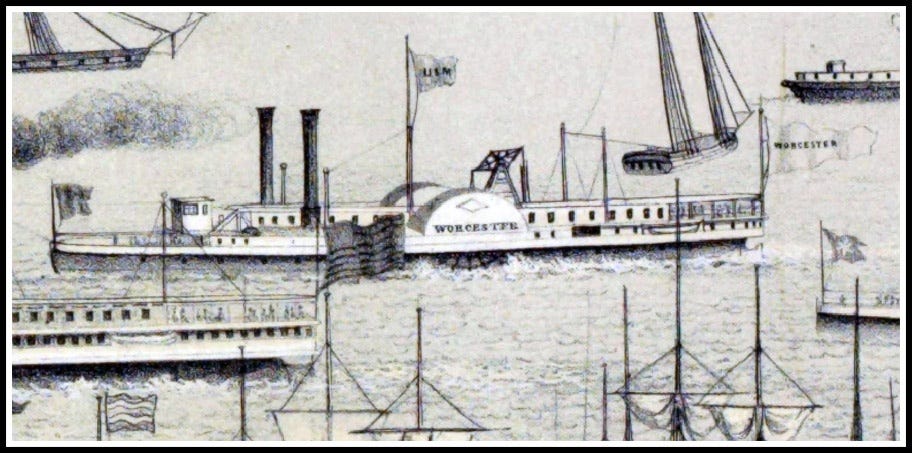

Norwich & New London Steamboat Company’s steamboat Worcester was scheduled to leave Pier 18 at 5pm that day, carrying this letter. This was contract route number 802.

The Worcester landed at Groton, Connecticut (across from New London)

The letter was taken by coach inland to Allyn’s Point where it could take route 674 on the Norwich & Worcester Railroad

Once at Worcester, the letter was transferred to the Boston & Worcester Railroad (Route 605)

Pier 18 was part of a long line of piers along West Street bordering the Hudson River. The crossing streets, such as Courtlandt, provided guidance to those who might not be as familiar to the actual location of a given pier number. Hence the newspaper advertisement’s full instructions were “Pier 18, foot of Courtlandt Street.”

Some period maps, like the portion of an Ensign and Thayer map shown above, provide shipping line names if a peir was assigned to a particular company. In this case the text reads “Norwich S.B. 18.” This provides us with primary source confirmations that we are seeing things right for this stage of the journey.

Another map produced by James Miller can be found at this link in the Library of Congress website. Pier 18 is labeled there as “St.B. for Boston” (Steam Boat for Boston). It would be tempting to conclude that this steamer would go directly to Boston, but we know from other sources that off-loading at Norwich would be much faster. “Steamboat for Boston” would be referencing the route to get to Boston, not the eventual destination of the steamboat.

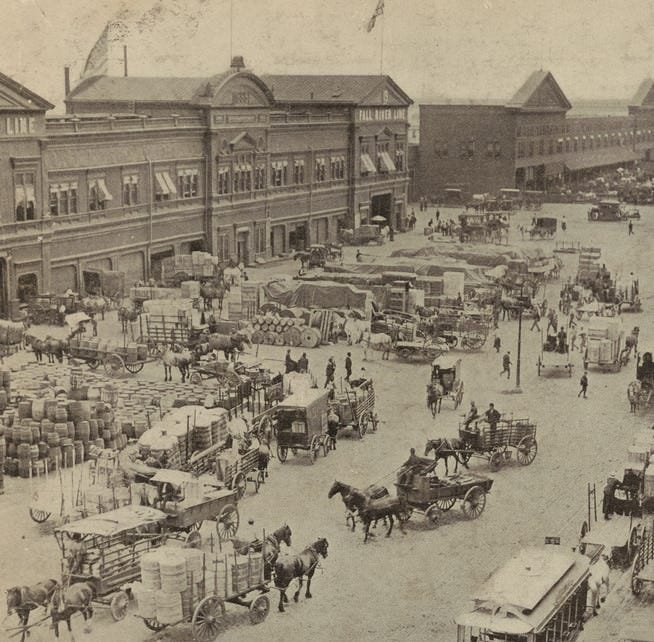

The area near the piers on West Street would have been incredibly busy with ships loading and unloading and carts hauling goods to and from. There would have been places where people could board or depart ships (the New Jersey Ferry was located nearby on Pier 17). The drop box for mail would have been located somewhere just off the right edge of this photograph - if I were asked to make an educated guess.

The Norwich and New London Steamboat Line started in 1840 and was initially part of the Norwich & Worcester Railroad company. It would not be until 1848 that the steamboat line would be organized as its own company. The company continued to provide this water until 1860, when it was dissolved.

The first section of the Norwich and Worcester Railroad was opened in 1840 and the second section to Allyn’s (or Allyn) Point was in operation by 1843. The final section that would connect the railroad directly to the port at Groton would not open until 1889.

The final leg was handled by the Boston and Worcester Railroad which was established in 1835, making it one of the earlier railroads in the United States. The broadside advertisement from 1843, shown above, illustrates multiple trips on this route were run each day. The image above advertises the connection from the Norwich Railroad as the second train of the day. Obviously, things probably changed from 1843 to 1850, so the schedule was likely different and probably more complex than the one shown here.

It is interesting to note that both advertisements in the paper and this broadside make reference to carrying the mail. It’s a good reminder how important postal services were for communications in the 1800s.

Thank you again for joining me for Postal History Sunday. Have a great remainder of your day and a fine week to come.

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack. And, some publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest.

Not only a great story this Sunday, but incredible photos and illustrations!

(I was on the road doing some volunteer work this weekend, so it became my bedtime story! Thanks, Rob!!)

I appreciate your expansion from pure postal history facts to a broader view of the companies and economic and cultural settings to which these postal artifacts give witness.