It's just an envelope. Not only is it just an envelope, it's an envelope that has already performed its duties in this world. It no longer carries any contents. And how could it? The back has a big slice in it that would make it all the more difficult for it to contain whatever a person might want it to hold.

I suppose it has the redeeming feature that it is old. A little over 158 years old, in fact. And, humans are kind of odd about the age of things. First, an item is new and we are most pleased to have it. Then, the item sees a little use and it becomes "old and used" and we don't want it anymore - or at least we want something newer or unused. Then, after a certain number of years - if that item has somehow survived the world - it becomes desirable once again.

That's how it is with so many pieces of postal history. Because they are seen as windows into a past that is now old enough to be the attractive sort of "old," a torn envelope once again gets our attention. But, why this one? There must be hundreds and probably thousands of old envelopes from the 1860s that carried simple letters from one location to another in the United States for the cost of the 3 cent postage stamp found on them.

And in fact, that is a true statement. It is one of thousands in that respect. But, unlike many of those old envelopes and folded letters, this one has more clues that hint at a story more interesting than most.

A dead letter

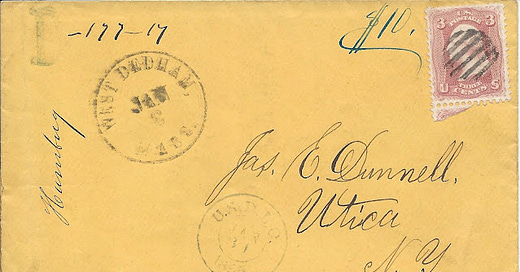

This letter was initially mailed at West Dedham, Massachusetts, on January 3 and is addressed to a Jas. (James) E. Dunnell in Utica, New York. The contents must not have weighed anything more than one half ounce because the three cent stamp paid for a simple letter to a destination within the United States.

However, James Dunnell never did get this letter, instead the envelope and its contents took a trip to the Dead Letter Office.

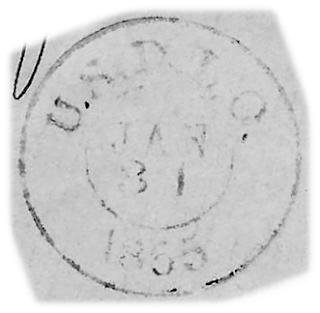

The marking towards the bottom of the envelope reads U.S.D.L.O. Jan 31 1865. The abbreviation stands for United States Dead Letter Office, which was located in Washington, D.C.

The US Post Office actually split Dead Letters into five categories:

Letters that remained at the post office unclaimed (typically after one month).

Letters that were deemed unmailable because the address could not be deciphered, was incomplete or the content was deemed to be "obscene."

Letters where no attempt to pay postage was made (or someone tried to re-use a postage stamp). These were classified as held for postage.

Packages over 4 pounds in weight

Letters refused at the post office by the recipient.

The Utica post office was probably small enough that they would typically send a bundle of dead letters to Washington, D.C. once a month - typically towards the first of each month. So, a receiving marking of January 31, 1865 seems to fit the pattern.

The Utica postmaster was supposed to classify each item being sent to the DLO under one of these categories by writing on the front of the letter.

Classifying Dead Letters

Of course, not everyone follows instructions. So, I was not too surprised that I couldn't find any of the words I highlighted above: unclaimed, unmailable, held for postage or refused. And, this clearly wasn't a package that weighed more than 4 pounds - so it wasn't that. We can also remove "held for postage" from the option list because it appears to be properly paid.

So, this item was either unclaimed, unmailable or refused by the addressee.

Instead, the postmaster in Utica wrote this word on the front of the envelope.

Humbug

The word "humbug" first appeared in dictionaries in 1798 and it described a deception imposed upon another person. In fact, humbug was pretty commonly used in the United States, including with respect to the secession of the states that formed the Confederate States of America.

The whole concept of a humbug becomes very clear when you view the image. The very pretty idea of secession floats over the edge of the cliff, promising one thing - while the reality of plunging to the breakers of the ocean awaits those who fall for the humbug.

On a less grand scale, humbug was often a reference to a person who represented themselves as someone they were not - often in an effort to defraud others. The image shown below depicts a person making a claim to be able to raise the devil. While they do so, to the amazement of the targeted individual, an assistant deftly removes valuables from the target's pocket.

And, of course, you can always remember Scrooge and his "Bah, humbug!" It was simply his way of making a claim that the festivities and celebration of Christmas were just a big hoax.

So, apparently, the postmaster felt that James Dunnell was a humbug of some sort. But that still leaves it up to our interpretation as to how they actually classified this item. Was it unclaimed, unmailable or refused?

We can almost certainly say the letter was not refused, so it was either unclaimed (because Dunnell had skipped town) or deemed unmailable because the postmaster was already aware that Dunnell was running some sort of scam through the mail.

However, the law frowned mightily on postal employees who withheld the mail from an addressee, no matter how much they might know about their humbuggery. So, it is fairly likely that this was essentially an "unclaimed" letter after it was held at the Utica post office for the required time period. But, if the Utica postmaster wanted to call attention to Dunnell, they could have bundled it up with the unmailable items and sent it on to the Dead Letter Office.

In any event, the postmaster was not allowed to open the letter - that was for those in the Dead Letter Office to do.

Fraud and the US Mail

Perhaps, it might seem that I took a bit of a jump in logic that Mr. Dunnell was a fraudster perpetuating a humbug on the public. After all, I've only given you the word "humbug" on an envelope to back it up. So, I offer this as well.

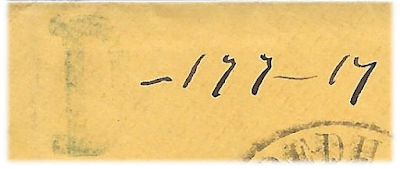

One of the duties of the Dead Letter Office was to identify valuable contents and see if they could determine who had sent them so it could be returned. It was quite common to send cash through the mail at the time and, sure enough, there is a note that, when it was opened at the DLO, it was found to contain ten dollars in cash.

In fact, this amount is also written on the back of the envelope. I am guessing that the letters that precede could be the initials of the DLO employee who processed the letter.

With the increase in use of the mail, came an increase in scams and, well, humbugs. Popular humbugs included highly touted (but unlikely) medical cures and illegal lotteries. Since lotteries were banned in most states in the 1860s, it would be normal for a person wishing to participate in one to send money via the mail. How hard would it be for a person to send out a mailing using special printed matter rates advertising a lottery at the cost of one dollar per entry? It wouldn't take much to pocket the money and run. After all, most people lose the lottery - so who's going to follow up?

Lotteries were a good opportunity to be a long-term humbug, as we can see if we look at the Louisiana Lottery that started in 1868 and lasted until 1893. While this lottery did pay some money out, they certainly were not above bribery to get officials to look the other way if they were less than above-board. And, of course, they did what they could to stack the odds. If there were unsold tickets, they still put them into the lottery. And, if one of those were pulled as a winner, the money would go to (or stay with) the Louisiana Lottery itself.

If you're wondering why so many people were willing to be taken by scams and humbugs such as these, all you need do is read the short story by Anton Chekhov titled the Lottery Ticket. The hope and dreams that come with the possibility of winning, no matter how remote, is difficult to deny.

By the time we get to the mid 1860s, mail fraud was a big enough deal that legislation was offered in 1866 and enacted in 1868. It became illegal "to deposit in a post office to be sent by mail, any letters or circulars concerning lotteries, so-called gift concerts, or similar enterprises offering prizes of any pretext whatsoever."

But, postal employees were still more concerned about avoiding any delay of mail delivery because an 1836 law set harsh penalties for a postal service employee that hindered the progress of the mail. It was not until 1872 that the law was modified to make the mailing of matter that was intended to defraud a misdemeanor.

Dead Letter Office at work

The Dead Letter Office was the last chance for an item to either find its way to the intended destination or to be returned to the writer, along with potentially valuable contents. The first step was to do what was called a "blind read" where workers would attempt to make sense of the address and addressee without opening the item. If that step failed, the item was opened in an attempt to either decipher the intended recipient or return it to the writer. This process was remarkably well done, with over 40% of the items finding their way out of the DLO to a proper home.

However, most items with no value that could not be returned or delivered were fated to be destroyed. Items with value, on the other hand were authorized to be auctioned off, according to Sec 391 of the 1866 Regulations of the Postal Department. A few interesting or unique items were maintained in a makeshift museum kept at the DLO and was of great interest to the general public.

During the Civil War, for example, numerous young men went to war and arranged to have their photographs taken with the intent of sending them to loved ones. Unfortunately, many had never sent a letter before and their effort to provide legible and clear addresses often failed. Many of these photos were posted in the post office lobby (see the video below) in an effort to help people find photos of those they knew. In fact, many of these photos were not destroyed during the normal time period out of a sense of patriotism and efforts to find relatives and loved ones to take the photos went on for some time.

To give you an idea as to the scale, the Report of the Postmaster General for 1864 indicated that 10,918 dead letters containing daguerreotypes or photographs were processed (page 17 of the report). Most of these were "sent by soldiers or their correspondents." The report for 1868 showed a dramatic increase to 125,221 dead letters with similar class items (photos), but they were clearly not for the same reasons (soldiers serving in the Civil War). It simply is an example of how the volume of the mail (and the possibility for items to need the services of the DLO) was expanding.

If you would like to read a little bit more about the Dead Letter Office, I found this blog entry on the philatelythings site to be enjoyable.

File under "D"

Perhaps you noticed the hand-stamped letter "D," followed by a series of numbers at the top left of the envelope. Well, there needed to be some sort of filing system, given the volume of mail being processed at the Dead Letter Office. The first letter of the last name of the recipient was typically used - so the "D" of "Dunnell" provided this particular letter with it's initial file letter. I have no idea how the rest of the numbering system was supposed to work. So, if someone happens to know, let me know and I'll share it later.

So, what was Dunnell up to?

I was hopeful, of course, that I might be able to dig up some sort of clues as to what James Dunnell might have been doing that would cause the Utica postmaster to declare him a "humbug." Like today, there certainly was no shortage of cons and scams that a person might perpetrate on others. Unfortunately, even after digging for a while in the Utica newspapers from that time period, I came up with nothing.

This is where I ask for help! If you are reading this and you think you have a lead that can help me find out what Mr. Dunnell's humbug was, please let me know!

This letter was a success for the DLO

Clearly, this particular letter was successfully delivered, probably to the writer who sent it to Utica in the first place. We know this because if it had not been delivered, the envelope would have been destroyed by the Dead Letter Office.

Humbug averted... until another unlikely prospect turned their eye. Or we can hope they learned their lesson.

Thank you for joining me today! Have a fine remainder of your day and an excellent week to come.

Additional Reading

Here are some recommended links to other Postal History Sunday articles that are related to today’s topic.

You Can’t Get There From Here - PHS #106

Not Called For - PHS #81

There and Back Again - PHS #30

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. Some Postal History Sunday publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest.