Welcome to this week’s edition of Postal History Sunday!

This week we’re going to look at mail items that qualified for special postal rates typically referred to as printed matter. Content might be legal papers or manuscripts, newspapers and periodicals, or promotional materials.

And, yes, even “junk” mail.

But, first, a little bit of business as we continue to make the transition from the old blog home to Substack. Let me encourage you to subscribe to Postal History Sunday and/or our companion farm blog, Genuine Faux Farm. It’s easy to do and you can get content notifications sent to your inbox to make it easier to find new material as it is released. Shorter entries can be viewed in their entirety, while longer ones may require that you click a link to view the whole thing.

If you are not comfortable with following the buttons below to subscribe, you can contact me and tell me that I can add your email to the free subscription list.

I will not push the subscriptions too often as I dislike self-promoting (it’s a personal failing or virtue depending on how you look at it). But, it does help me to know that people are actually able to access the content they are interested in.

And now to the main event!

Business Papers as Printed Matter

Let’s start with this large, and somewhat battered, envelope mailed from Paris on July 9, 1862 to Chateau Thierry - also in France. There are two 20-centime postage stamps and one 10-centime stamp paying a total of 50 centimes in postage and it is very clear that this envelope held a fairly sizable stack of papers when it was mailed.

The “business papers” rate for France in 1862 was 50 centimes for up to 500 grams in weight (Aug 1, 1856 - Aug 31, 1871). To show you the potential savings, a 500 gram piece of letter mail would have cost 4 Francs (400 centimes).

The reduced rate for business papers in France is one example of a printed matter rate. Content could qualify for the special rate as long as it did not include “actual or personal correspondence.” In other words, the pre-printed content was okay, but you couldn’t include notes in the margins about your Great Aunt Margaret and the time she forgot the words to her favorite tune.

Initially, any handwritten notes could disqualify items from this discounted rate. But, on May 25, 1859, handwritten annotations on the business papers (or other documents) were permitted. However, the restriction against adding “correspondence,” including the story about Aunt Margaret - regardless of how good that story might have been - remained.

While this old envelope no longer has any of its contents, I was able to search for information regarding G Morin at 6 Boulevard de Strasbourg in Paris - the sender of these documents. I discovered an M Morin in 1861 that advertised properties for sale. Further digging leads me to believe that G Morin and M Morin worked together to broker properties. It would not be uncommon for real estate paperwork to be sent using printed matter rates.

Wrappers to Hold It Together

This item, mailed from the United States to Munich, Bavaria, in 1893, illustrates another way a mailer could package content that qualified for special printed matter rates. Philatelists (stamp collectors) would call this a wrapper, which was simply a wide strip of paper that was glued together to make a tube. Typically, the contents would stick out of either end (at the right or left of this piece).

One of the requirements for items to qualify for printed matter rates in the United States (and many other countries) was that it should be easy for postal clerks to inspect the contents to ascertain that there was “ineligable content” included. One approach was to leave envelopes unsealed. Another was to use a wrapper that would allow a person to pull the contents out, look at them, and then put them back in.

The wrapper shown above has a preprinted design in blue that represents one-cent of postage. One-cent would have been a common amount for printed matter within the United States. But, since this letter was going to Germany, the cost of postage would be greater and a one-cent postage stamp was added to pay that extra cost.

And yes, mailing newspapers used to be a thing. Actually, it used to be a very big thing. Postal regulations and postal treaties between countries in the 1850s and 1860s typically included whole sections on how newspapers would be handled.

Newspapers as Printed Matter

I realize that newspapers and magazines no longer hold the same prominence in our culture as they did even a decade or two ago. But in the 1860s and 1870s, periodicals required substantial attention from the postal services around the world to get these items from the publisher to their various destinations.

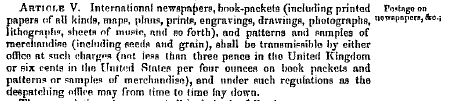

While letter mail was typically the first thing addressed in postal agreements between countries, they could not escape the fact that newspapers and other printed documents required a different type of handling. You certainly don't have to read the blurb shown above. It's just a sample of text from the 1867 convention between the United States and the United Kingdom that mentions newspapers and other "printed matter." I offer that illustration for two reasons. First, to show that newspapers and similar printed matter were often given different postage rates than letter mail. And second, handling this kind of mailed matter was different.

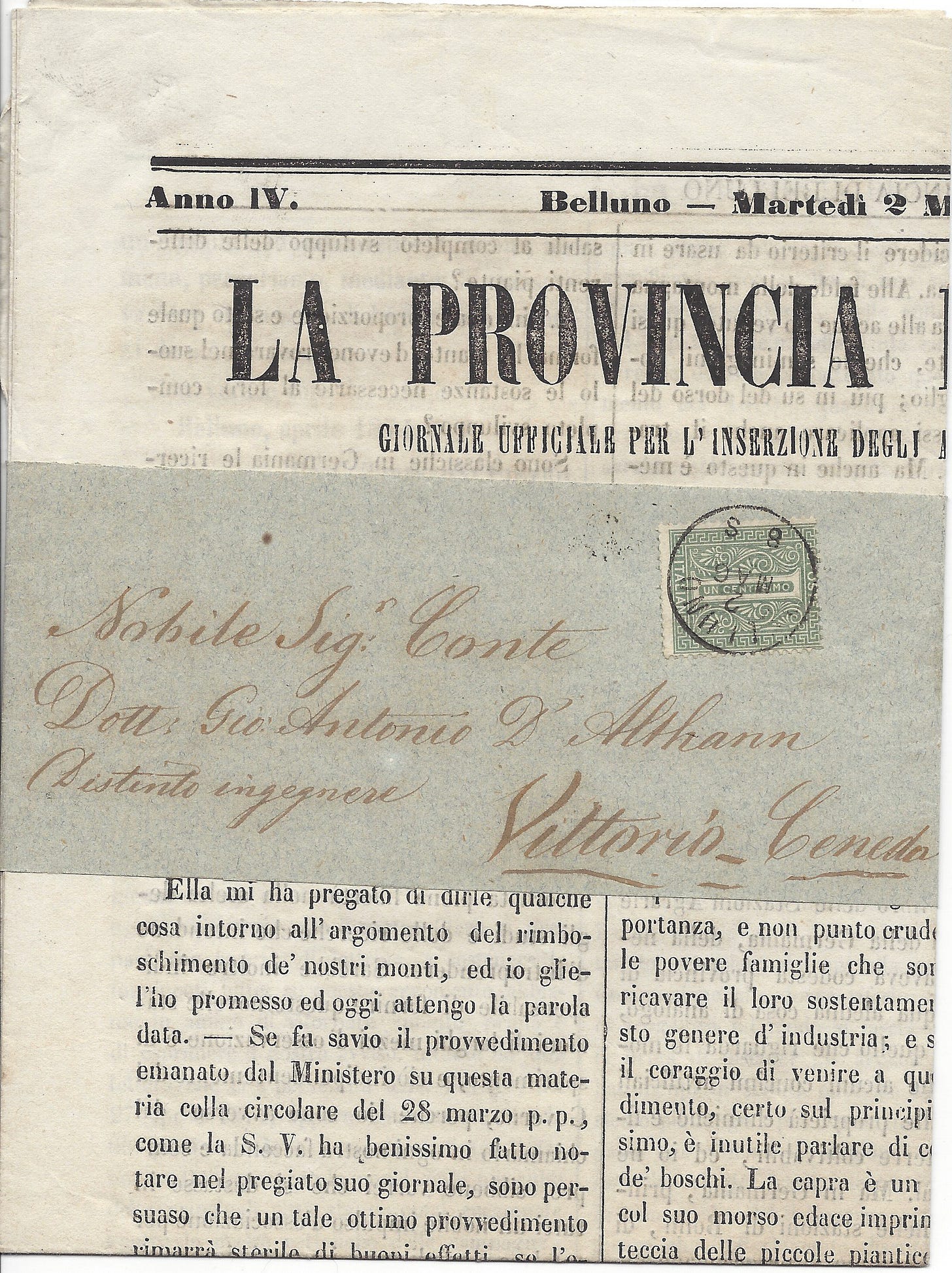

The Belluna, Italy, newspaper (dated March 2, 1871) shown above was enclosed by a paper wrapper band that served as a surface for the mailing address and postage. The band also kept the newspaper together and prevented it from inconveniently opening up while it was in transit through the mail services. The Belluno postmark is also dated May 2nd and the newspaper arrived at the Vittorio post office the same day according the marking on the other side of the wrapper.

It almost looks as if this particular newspaper has not been removed from the wrapper band. I suppose I could gently remove it to view the rest and then work carefully to put it back in the wrapper.... but, maybe not. I'm pretty happy with it the way it is. That, and, well, the news is probably a bit dated.

And - I don’t read Italian well enough to get much out of it even I wanted to without some struggle.

We could speculate as to the reasons why this particular artifact remains in this condition nearly 150 years after publication and mailing. Perhaps this item arrived while the recipient was away and they never did get caught up on the backlog of papers when they got home? I would find it hard to believe that someone would read the paper and then painstakingly fold it up and put it back in the wrapper.

Special Newspaper Stamps

It is a bit more common for a person to find a wrapper without the contents, such as the item shown above. This wrapper band is postmarked on December 12, 1920 in Prague, Czechoslovakia, and is no longer completely intact.

The newspaper postage rate in Czechoslovakia was intended for periodicals published at least four times per year with a maximum weight allowed of 500 grams. This particular rate (5 haler per 100 grams) became effective on October 1, 1920, but there was no 5 haler newspaper stamp available. There were stamps with the 2 haler denomination, so it became common practice to split one of these stamps diagonally to represent 1 haler in newspaper postage. In philately, this is known as a bisect or bisected postage stamp.

If you were paying attention, you might also have noticed that I called these newspaper stamps. These stamps were only intended to pay the postage for items that qualified for the newspaper rates.

Getting back to our original newspaper with the band still intact, we see that it has a 1 centesimo stamp on the wrapper. The stamp shown there was not a specialized newspaper stamp and it served as a regular issue postage stamp, available to show postage was paid for letter mail and newspaper mail alike. The bulk rate for newspapers in the Kingdom of Italy at the time was 1 centesimo per 40 grams (effective January 1, 1863), which explains its use.

But, it is possible that it actually cost the publisher of this newspaper less than that to get this copy to its customer in Vittorio. Wait… what?

Read on! We’ll get to that!

Letter Mail Rates

Let me back up for a second so you can see the whole picture. Above is a piece of letter mail. It cost 15 centesimi to send this folded letter from Chiavari to Torino, Italy. The envelope is a personal or business correspondence (not printed business papers like our first item) and it weighed no more than 10 grams.

Letter mail provided great flexibility. You could seal it up, placing whatever you wanted (within reason) inside the envelope or folded letter - as long as it was flat. The only reason the postal service might open the letter is if they couldn’t find the addressee and it went to Italy’s equivalent of the Dead Letter Office to be processed.

You could include a picture, an invoice, paper money, a newspaper clipping, a lock of hair and even, perhaps, the letter you got from Aunt Margaret so your cousin could read it too. You just simply had to pay the higher letter mail rate to send it on its way.

Printed matter rates

Printed matter mail, on the other hand, could not be sealed up. It had to allow the postal workers to be able to check contents to be sure there weren't personal messages or other non-permitted material being snuck in with the mailing! If a postal clerk found something that failed to meet regulation, they could require more postage to pay the letter mail rate.

The item above was simply sent as a if it were a folded letter, but there was no wax seal to hold the contents closed. This met the requirements for printed matter and allowed it to qualify for the non-bulk rate in Italy starting in 1863. It was mailed from Torino to Allessandria (both in Italy) for 2 centesimi for an item weighing no more than 40 grams.

Printed matter was 2 centesimi for 40 grams versus 15 centesimi for 10 grams for letter mail.

Now I think you can see the cost advantage for newspapers, magazines and advertising!

It certainly makes makes sense from a business perspective. In the case of a newspaper, people were used to paying 5 to 10 centesimi for a single copy of a newspaper at a newstand. Even if you could pass your costs on to the customer, it was unlikely that readers would pay too much more for the privilege of mailing it to their home address.

And, by providing lower rates for mass mailings, postal services were able to capture the lucrative business of transporting this type of material.

Newspapers and Journals

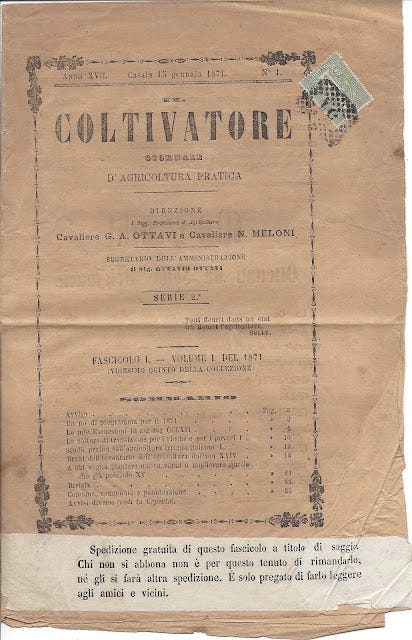

The next item is a sample Farmers' Journal of Agricultural Practices in Italy. The white band at the bottom tells the recipient that this sample is being provided 'gratis' and that the recipient should not delay in sending in for a subscription! At top right is a 1 centesimo stamp that is paying for the mailing of this item from Casale Monferrato - just like our Italian newspaper.

But, it is quite likely the cost to each of these mailers was LESS than 1 cent per copy being mailed.

There was a concessionary rate that provided a discount for newspapers and magazines that pre-sorted their bulk mailing by the destination and the route the items were to take to get to that destination. While this and our first newspaper item were mailed under the 1 centesimo rate, we cannot be certain that was the actual cost to the publisher of either of these items because one of these (or both) may have been given this additional discount.

Some bulk mailers paid less than one cent per item if they were regular customers. A weekly newspaper, such as our Belluno newspaper, might qualify for a better rate than a monthly magazine. The thing is, there weren't stamps with denominations for all of these fractions of a centesimo - so they just used the 1 centesimo stamp and the bulk mailer simply paid the bill at the agreed upon rate. In some cases, the stamps were adhered to the newspaper before printing and you can find examples where the newspaper printing goes OVER the stamp.

If you think about it, this makes a great deal of sense for the post offices as well. They can count on consistent business rather than the whims of those who send a single letter at a time. A pre-bundled batch of newspapers to go from Belluno to Vittorio required about as much handling as a single letter from Belluno to Vittorio - until you got to the delivery part, of course.

Yes, publications and newspapers typically weighed more. But, there wasn’t all of the sorting that went into the letter mail process and that counted for something.

When I unfolded the Farmers' Journal item, I found it was a larger piece of paper that was printed as four separate pages on each side. Other than the title page, it was all advertising for agricultural implements, plant stock and other items. At a guess, the actual sample of the journal had been wrapped inside this covering and is no longer part of the whole.

Perhaps someday I will find an actual copy of this Farmers' Journal of Agricultural Practices. Then, I'll brush up my Italian - and learn something new!

Time Saving Innovations

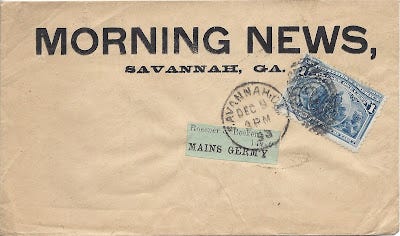

The Morning News item above was mailed in 1893 from Georgia to Germany and it does not have any content either. But, what it does show is that 'mass mailing' short cuts were already in use at the time. Preprinted labels for mailing addresses, for example! And, apparently, the Morning News from Savannah, Georgia was willing to spend the money to have pre-printed wrappers or envelopes for their materials.

And “Junk” Mail

Some types of printed matter mailings are harder to find than others. As far as promotional material was concerned…

Well, what do you typically do with junk mail? The content is not typically of a personal nature - and most people see no reason to hold on to it. Similarly, a newspaper was read and then discarded, burned or used in a bird cage as a liner. Wrappers or envelopes carrying periodicals or business papers usually have a slim chance of being saved - even if the content might be kept for record-keeping.

But, finding printed matter with both the content AND the wrapper? That can be even more difficult.

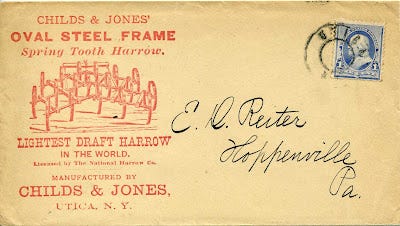

Shown above is an example of promotional material from the late 1800s to early 1900s that DOES have contents. These contents include multiple sheets highlighting the implements being offered by Childs & Jones.

It might be a little easier to understand how something might still have the contents if the recipient was potentially interested in a product. They might have decided to hold on to the envelope and the contents figuring they could reference it later if they decide to make a purchase. It was placed into a pile of papers or a file until… One day, it all gets cleaned up by a person who realizes someone might be interesting for collecting purposes.

Or not - and it goes into a dumpster or burn barrel.

And that's why it can be hard to find these things. Don't get me wrong, there are plenty of them out there for collectors to enjoy. But, consider how many of these were probably mailed and what a tiny percentage of them most likely survive to this day!

And there you are! You’ve just made your way through this week’s edition of Postal History Sunday. Thank you for joining me.

Have a good remainder of your day and a fine week to come.

Additional Reading

I have heard from some people that one Postal History Sunday isn’t enough on some weekends. So, here are links to other PHS that are related to today’s topic.

Expanding Horizons - PH #112 - a look at a specific piece of printed matter that refered to Alexander von Humboldt

Farm Palace - PH #125 - an amazing piece of “junk mail” featuring images of barns, tractors and silos for the Dickey Clay Manufacturing Company.

Humbug - PH #165 - an example of a letter that was sent to the Dead Letter Office in the United States

Telegraphs, Steamships and the Mail - PH #103 - a piece of printed matter mailed in Switzerland

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. Some Postal History Sunday publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest.

Another super article. Thanks