In Transit

Postal History Sunday #225

The end of the year with all of the various holidays is frequently a time for travel in our household. Just in the last month, we’ve taken numerous short trips to the center of the state for a range of reasons - including farm business, professional conferences, and the pleasure of seeing family.

While I actually prefer a physical map when I am a navigator, I will admit that travel and mapping apps have their moments. Not many - but they have them. As I was looking at the instructions given to get us from point A to point B, I was struck by how the bulk of our travel could be summarized in one line. Meanwhile, the last several blocks - with all of its twists and turns - took up most of the description.

This makes sense, of course. The list of directions only concerned itself with navigation points that would require a significant change in our driving. Things like a turn to the north or a point where we would merge with a new highway.

This felt like a nice illustration to explain some of the postal markings that can be found on covers in the mid-1800s. And, if you don’t see where I am going with this introduction - stay tuned - because it’s time for Postal History Sunday!

The Beginning and the End

Postal markings come in all shapes and sizes, but the most common would be the date stamps that include the post office where a piece of mail originated. Even today’s mail continues the tradition of marking the mail with an originating time and place. The biggest difference is that the machines that apply these marks are located at bigger mail processing centers. A person in a small town could mail an item at their local post office and find that the postmark is from a larger city some distance away.

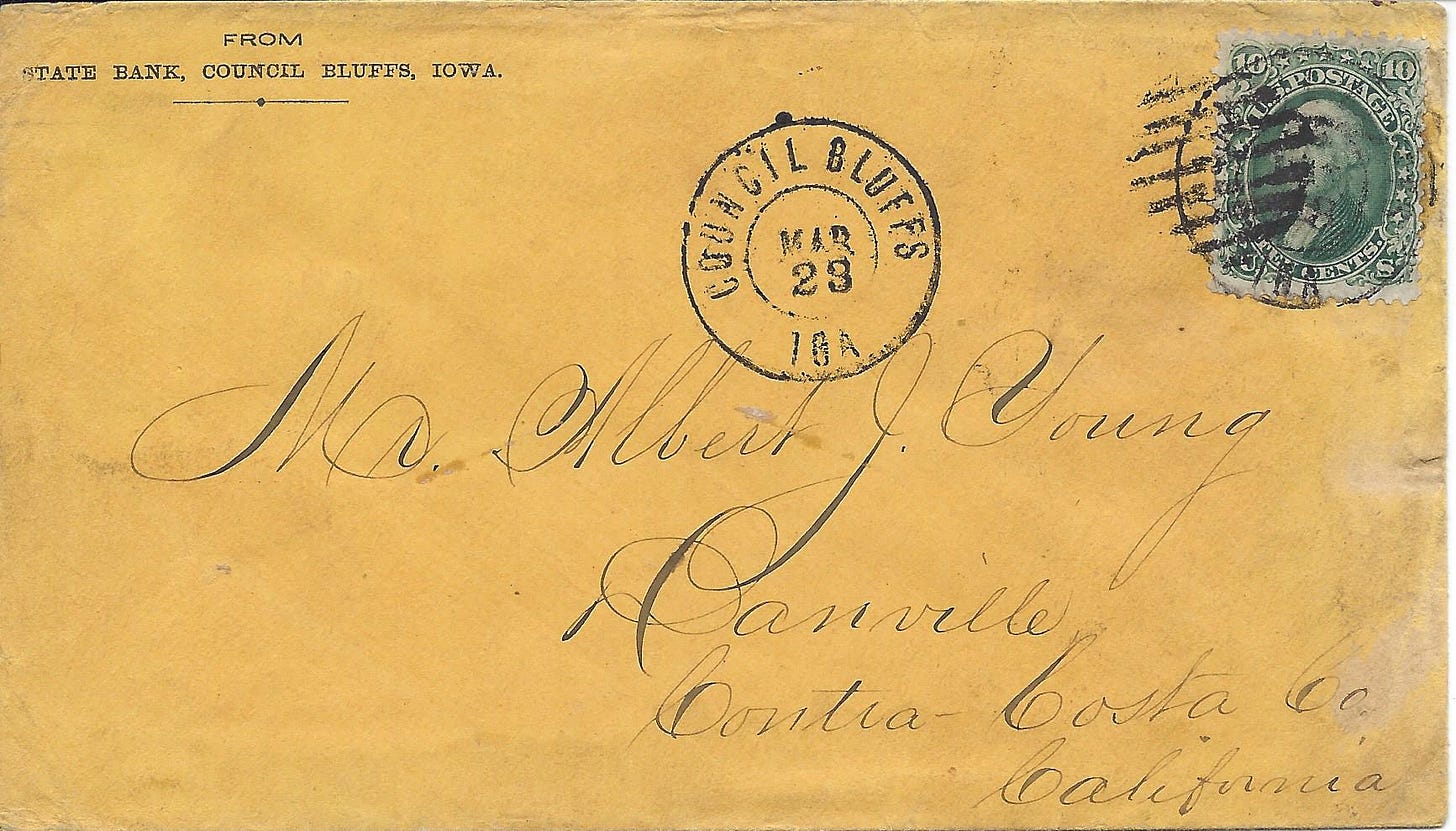

During the 1860s, the origination postmark is usually a reliable way to determine where the piece of letter mail started it’s journey. The envelope shown above sports a nice Council Bluffs, IOA (Iowa) CDS (city date stamp) for March 23. The printing at the top left helps confirm the origin, indicating that the State Bank at Council Bluffs was the sender of this letter.

In addition to the CDS, there is a barred circle that served as an obliterator or cancellation. The intent of the cancellation marking was to mar the postage stamp sufficiently so that it was difficult to re-use it for future correspondence. This was also applied at the Council Bluffs post office to indicate that they recognized the payment of postage.

As you might guess, there is more that I can say about this particular cover - but we’re going to stay with the theme for the time being. Perhaps I’ll have energy and time to do more later in this article. If not, I’m sure it will appear in a later PHS.

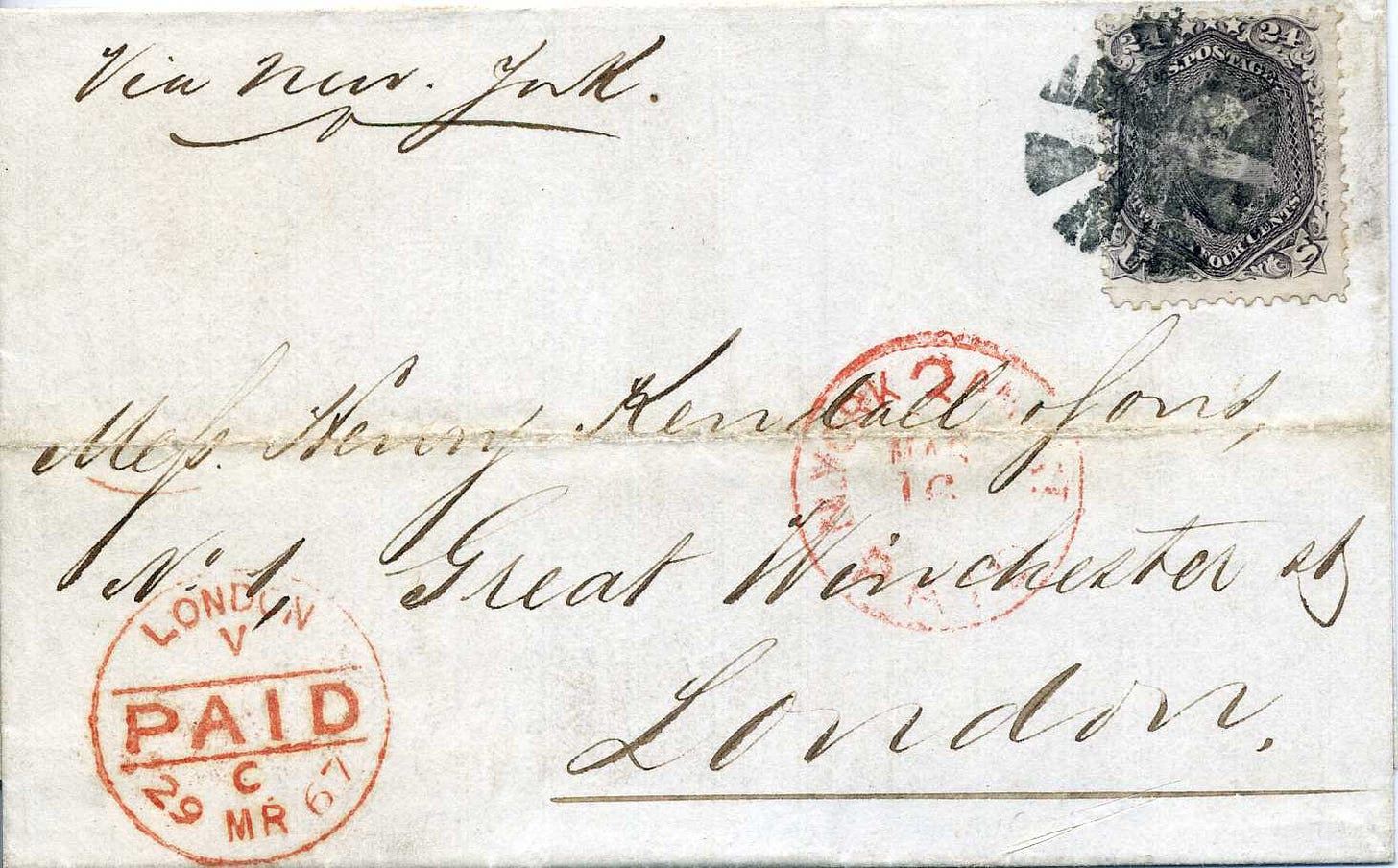

The cover shown above is actually an exception as it does not include a postmark for its point of origin. The earliest postal marking on this item was applied in New York City on or just before March 16, 1867. The red exchange office marking indicates to us that it was intended to leave on a ship to cross the Atlantic on the 16th of March. There is also a black circle of wedges obliterator that was applied to cancel the 24-cent stamp.

However, there is a sneaky clue that told me I should look a bit more closely at tis cover. The docket at the top left of the cover reads “via New York.” Logically, it wouldn’t make much sense to write that docket IF the letter originated in New York City.

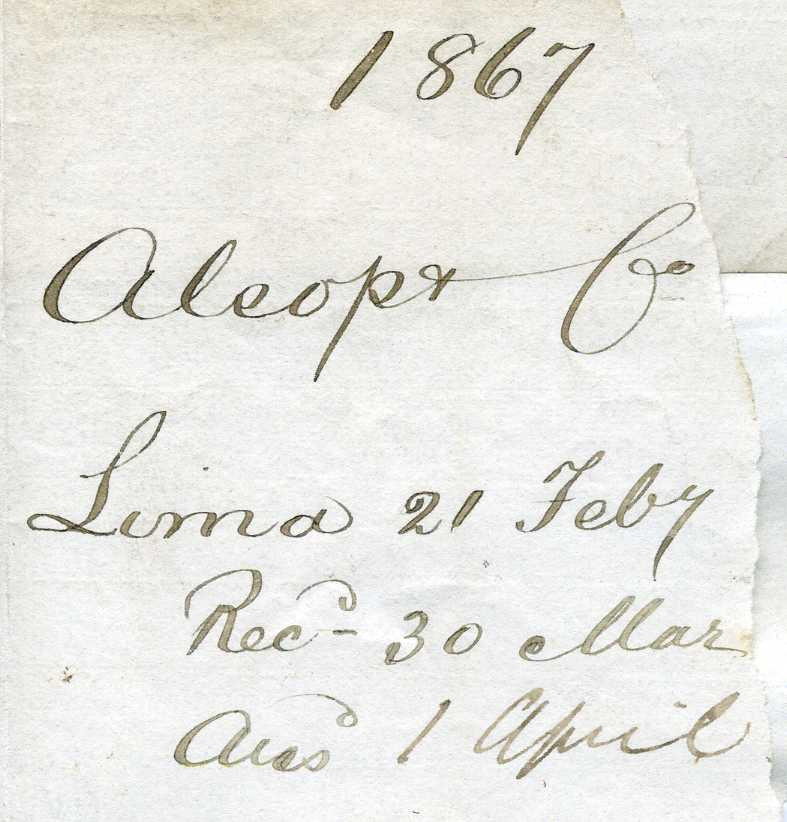

While the contents of the letter are missing, there is still a docket, written by the recipient in London, that provides us with more information. This letter actually started its journey in Lima, Peru, on or just after February 21st. It ended its journey in London on March 30th and the recipient sat down and answered this letter just two days later on April 1st.

I hope it wasn’t just a letter full of jokes and misinformation. Since I brought THAT up, I thought I would share this article by Angus Kress Gillespie that explains the origins of April Fools.

I’m beginning to think I picked the wrong topic for today and this one should be moved to four months later!

Getting back to the matter at hand - there are a few possible reasons that might explain the absence of a Lima postal marking. The most likely is that this letter was sent from Lima to New York under a separate wrapper to an Alsop & Company representative in the US. That person then took this letter (and possibly others) out of the wrapper, applied the postage and mailed the letters at the New York Foreign Mail Office.

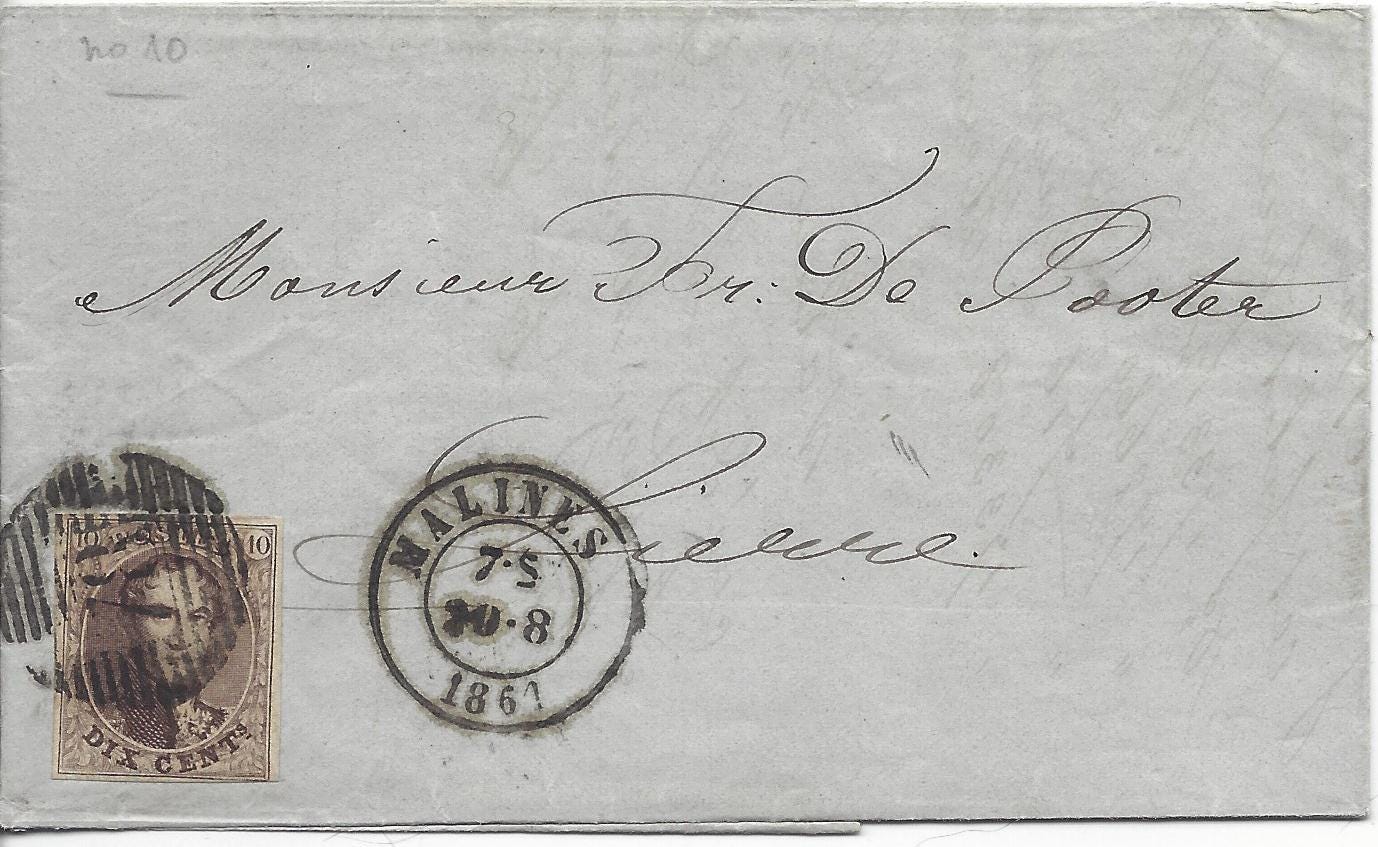

While the first cover featured today only showed a postmark for the origin, some countries were very interested in providing evidence as to both the origin AND the destination. Starting in the 1840s, Belgium worked very hard to develop efficient rail lines, partly with the hope that they could capture lucrative business carrying mail, goods and passengers. What better way to show the efficiency of their transportation system than to show the speed of mail travel?

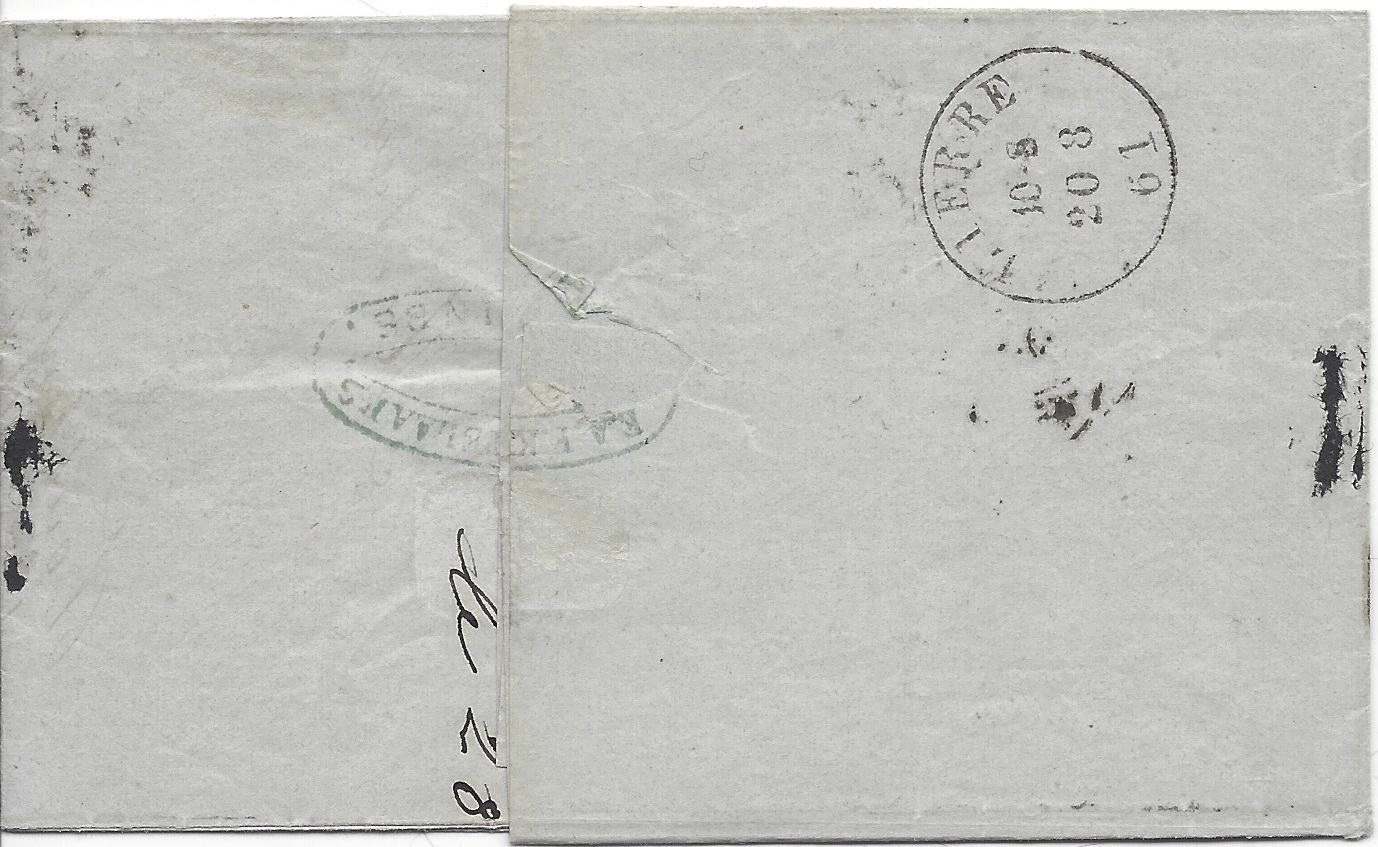

The 1861 folded letter shown above actually did not travel very far. The ten centime stamp paid the postage for letter mailed at the shortest distance tier for Belgium internal mail. A bold Malines postmark shows both the date and the time the letter was processed at the originating post office. The marking tells us the letter was ready to leave Malines at 7:00 on August 20.

Belgian post offices usually followed the practice of putting their CDS post mark on the back of letters received and to be delivered. This letter does not disappoint us as there is a nice, clear Lierre postmark dated August 20 at 10:00. This provides evidence that the letter traveled from its origin to its destination in just three hours. Of course, this does not account for the time it took to deliver the letter to the addressee - but that was a different matter.

Fair Exchange

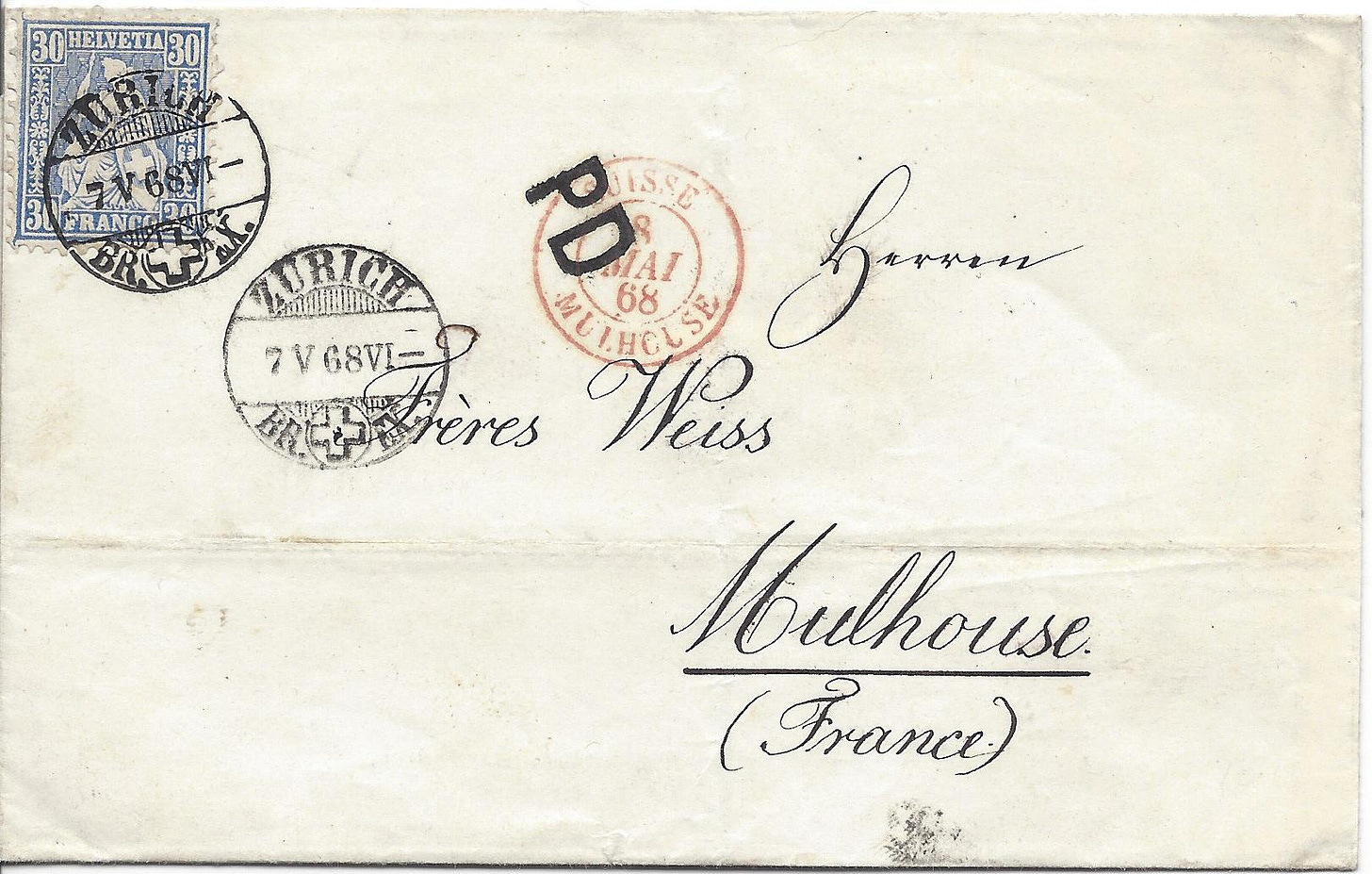

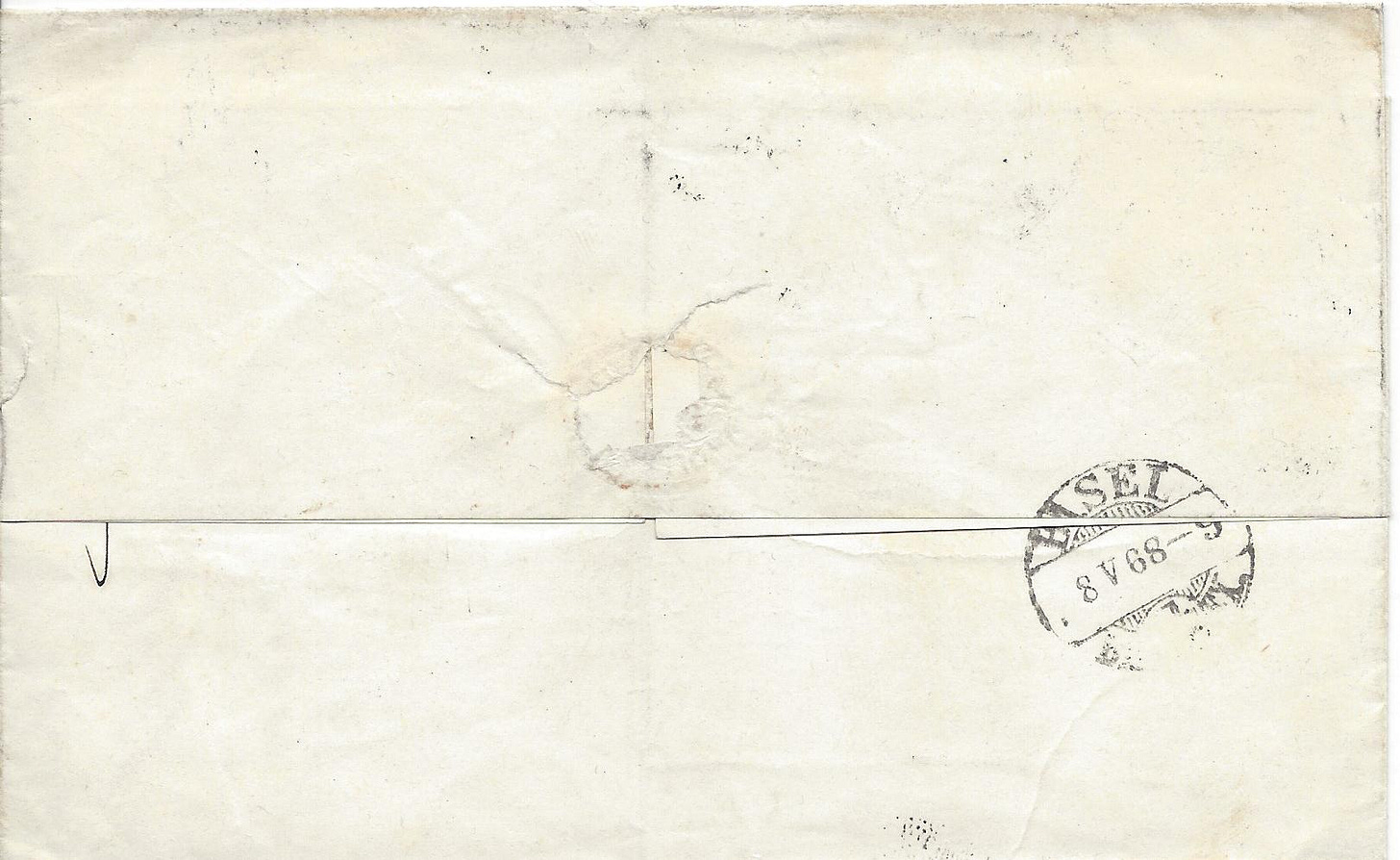

Another common postal marking can be found for foreign letters - or letters sent from one country’s postal service to another’s. These postmarks are known as exchange office markings. The letter illustrated above has one exchange office marking in red that reads “Suisse Mulhouse 8 Mai 68.”

During the mid-1800s, the exchange of mail between countries was often dictated by individual negotiated postal agreements (or conventions). These conventions could set everything from postage rates, routes for the carriage of the mail, exchange offices, and regulations for using postmarks to communicate the status of each letter.

For the letter shown above, the Swiss exchange office was Basel and the French exchange office was Mulhouse. The foreign mail office in Basel sorted mail bound for France, putting them into mail bags or pouches for each of the French exchange offices the agreement paired with the Basel office. Once in the pouch or bag, the letter was not removed until it was received at the corresponding exchange office. Many agreements dictated that there be a dated exchange postmark representing both the sending and receiving exchange office.

But, where is the Swiss exchange marking?

Ah! There it is!

Mulhouse was not a very large post office at the time, so it might seem odd that it served as an exchange office. However, we actually have a clue to explain the situation on the address panel.

This letter was sent to a business in or near to Mulhouse.

The bulk of mail coming through the Basel exchange office was exchanged with larger French exchange offices, like Lyon or Paris (among others). But, smaller communities near the border were often given exchange office status for mail in their area. After all, it didn’t make sense to send a letter past its destination to Paris or Besanscon or Lyon to get to an exchange office, only to send it back the way it came!

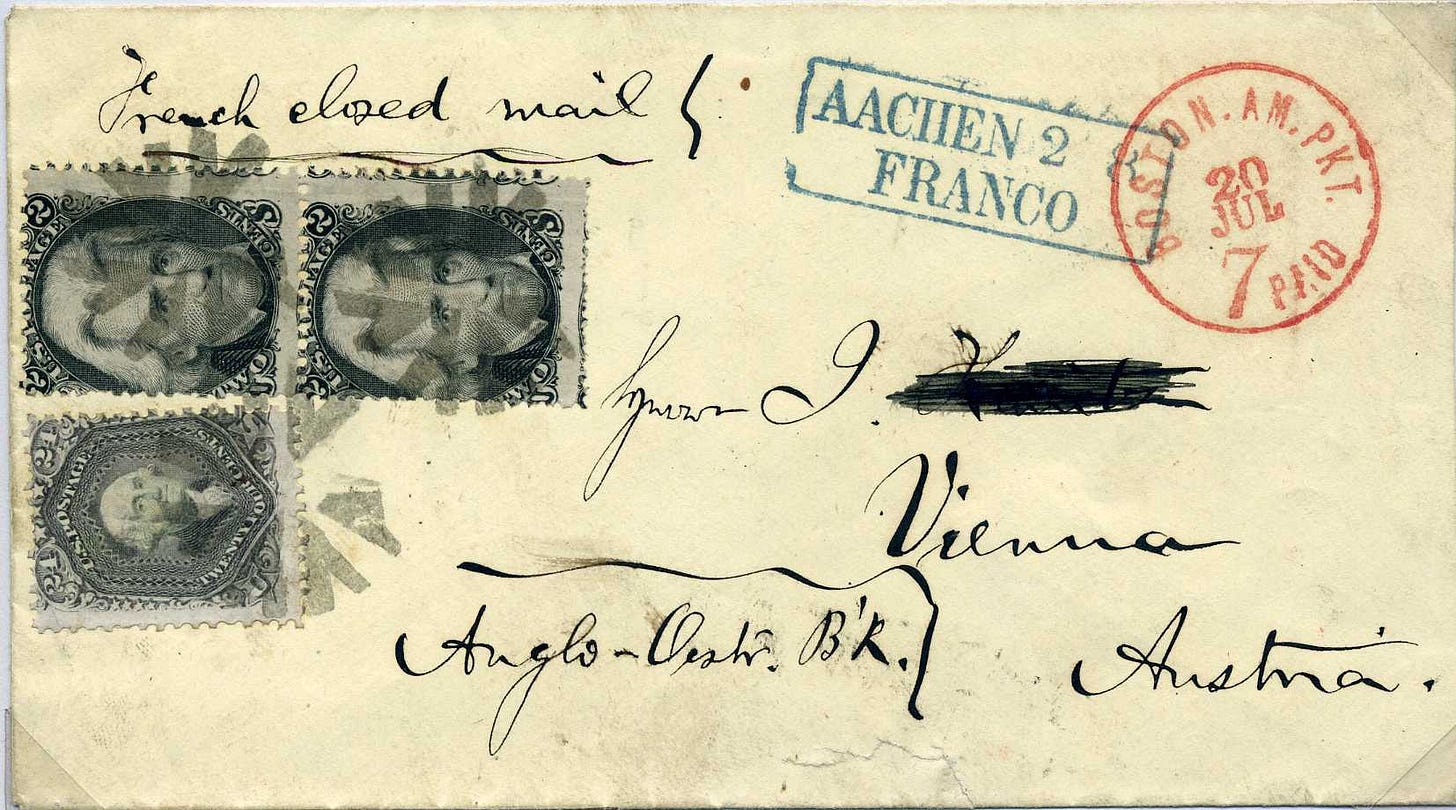

This 1867 letter from the the US to Austria features two exchange markings on the front of the envelope. The red, circular marking applied in Boston was applied by the foreign exchange office there. The blue, boxed marking was applied by the Aachen exchange office for the Prussian mail system. By simply looking at the dates on those two markings, we can answer the question “how long did it take to get from Boston to Aachen?” The ship left Boston on the 20th of July and the letter was processed by a Prussian mail clerk on August 2.

Remember, the European dating convention is to place the day before the month - so 2 / 8 would be August 2.

US exchange markings during the 1850s and 60s contained more information beyond a location and a date. You might have noticed that the Boston exchange mark includes “7 paid.”

These markings frequently confuse people who are learning about US foreign mail for this time period. If you look at the postage stamps, you will find that 28 cents in postage was paid. And, in fact, the postage rate for mail from the US to the Prussian Closed Mails was 28 cents per 1/2 ounce. That makes this a nice example of a simple letter. So, why in the world would Boston include “7 paid” as part of their exchange marking? Wouldn’t “28 paid” make more sense?

I agree that it would if you and I were the intended audience for the postal marking. But, I suspect they didn’t care what people 157 years later would think about the handstamps clerks placed on pieces of mail. Instead they were trying to communicate two pieces of information:

This letter was fully paid - hence the word “paid”

7 cents of the total 28 cents was to be sent to the Prussian Closed Mail system to cover their expenses. The remaining 21 cents was retained by the US to cover their expenses - including the journey across the Atlantic Ocean.

The Prussian exchange marking also sends information to postal clerks within the German Austrian Postal Union (GAPU) - especially the Vienna post office. The word “Franco” in the blue box marking was their equivalent to the word “paid.” This made it clear to the carrier delivering this letter that there was no additional postage to be collected from the recipient. All they had to do was hand the letter over and go on their way!

And Everything in Between

It’s possible that, by this point, you are starting to see some patterns that explain the existence of postmarks on letters during the mid 1800s. If you haven’t, let’s sum up what we know so far.

It was common practice for a dated postmark to be applied at the point the letter was mailed - at its origin. Many postal services also had dated postmarks for letters that arrived at the post office for delivery - at the letter’s destination. And, letters that were exchanged between countries often had a postmark applied at both exchange offices.

These are all points in a letter’s travels that a postal clerk had to handle the letter and sort it so that it would progress in the correct direction to get to its destination. The origin post office would have to send the letter in the correct direction (at the very least). It would not do to send a letter that was to be sent from Iowa to California on an eastbound train. The foreign exchange office would sort mail for France differently than mail heading to Prussia. The receiving exchange office in Prussia probably wouldn’t send letters destined for Hannover on the same trains as those leaving for Austria.

And the receiving post office would often have to sort the letter to the correct carrier route, post office box or other delivery location.

Which brings me to a postmark that is not an origin, destination or exchange marking.

The contents of this folded letter sent from Wien (Vienna), Austria tell us it was mailed on September 18, 1852 and the origin postmark has the same date (18/9). The destination, Wolfsberg, was also in Austria, so there will be no foreign mail exchange markings on this letter.

The origin postmark - Wien - was applied twice on the two postage stamps that paid 9 kreuzer in postage. So, they are effectively used as obliterating cancels. There is a Wolfsberg receiving marking on the back of the letter that tells us the letter was processed there on September 20 - just two days after the letter was mailed.

But, there is also one more postmark on the back.

Unfortunately part of this marking was removed when the letter was opened, but a little detective work helped me determine some of what this tells us. This is an example of a transit postmark that was applied in Bruck - on the way from Vienna to Wolfsberg.

In other words, Bruck was a point where the internal Austrian mail underwent some sort of processing so it could, eventually, get to its destination.

I was able to find maps of this area of Austria from 1852, but this 1918 map is very easy to read should help illustrate the situation. Bruck is actually located at a point where the main railway line from Vienna splits, with one branch heading west and the other heading south to Gratz. Wolfsberg is actually located on a minor railroad spur in 1918. But, in 1852 Wolfsberg had no rail service. Additionally, there was only one line leaving Bruck - the one that heads south to Gratz. Even that line was not yet complete, with the issue of the Semmering Pass delaying the connection of the northern and southern portions of the railway.

So, in 1852, this letter took a train from Vienna to Bruck. At that point, the letter was taken off the train and sent by coach or other means of transport to Wolfsberg. It doesn’t take much imagination to recognize that this would be a point in mail carriage that letters could be sorted and processed so they would travel in the correct direction from Bruck.

And now, perhaps, you understand how travel directions reminded me a bit of postmarks. We don’t bother giving a new travel direction if some sort of action needs to be taken. Similarly, a postmark is usually an indication that some sort of handling was required to get the letter to where it had to go.

Thank you for reading Postal History Sunday! Have a fine remainder of your day and an excellent week to come.

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack. And, some publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest.

As always, I enjoy your weekly posting. Why did you think the first envelopment started in Lima, Peru and not one of the various "Lima" cities sin the US? (e.g., OH, IL, NY, etc)? Was it the fact that it took so long to get to NYC? Thanks!!!