Merry Chase in Place

Postal History Sunday #187

Welcome to Postal History Sunday! Take a moment to take your troubles and use them as a bookmark for a book you don’t intend on finishing. Shove that book onto the bottom or top shelf so it is less likely you will accidentally pick it up again. Maybe they’ll sit in that book long enough that they won’t be relevant the next time you see them!

Instead, let me encourage you to put on some fuzzy slippers, grab a favorite beverage or snack (but keep them away from the paper collectibles and your keyboard), and relax for a little while.

Everyone is welcome here, whether you love postal history already or you are just passing through. Thank you for allowing me the chance to share something I enjoy. Perhaps you will find it entertaining and maybe - just maybe - you’ll learn something new!

Postal history could be considered an area of study for those who are academically inclined. But, most people who engage in the study of postal history would identify it, first and foremost, as a hobby. Many of those individuals are collectors, seeking interesting examples of artifacts that allow them to explore how mail has been taken from one place to another.

These old envelopes and folded letters often have interesting stories to tell, but it takes some effort to develop the skills needed to understand them. Some old letters satisfy the part of me that enjoys solving puzzles. Other covers (postal historians often refer to an individual piece as a “cover”) feel much more like a time machine. Sometimes, they become a surrogate for world travel. And they almost always satisfy the desire to learn new things or understand things I already know better!

Today, we’re going to look at the very busy cover shown above. This envelope was mailed at the Lombard Street post office in London on, or just before, October 1, 1864. For those who like “short stories,” the letter was sent as a registered letter. The total postage required to mail it was 1 shilling and 6 pence (18 pence). It arrived in New York on October 15. The addressee could not be found and the letter was eventually returned to the United Kingdom.

And my job here is done!

What? Why are you looking at me like that? Were you expecting something more?

Well, okay then! I guess I’d better write a little bit more.

A Registered Mail Item

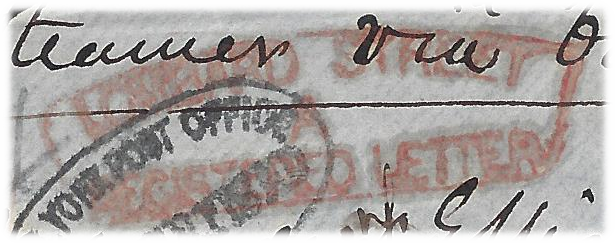

The first marking I want to call your attention to reads “LOMBARD STREET REGISTERED LETTER.” The person mailing this envelope apparently felt that the contents were important enough that it should be tracked more carefully by the postal clerks as this letter traveled from the United Kingdom to the United States.

The basics of registered letters in 1864 are actually quite similar to present day registration provided by the USPS. Today, if you wish to use these services, you have to pay additional costs. In return, the US Postal Service will carry your mail item so that they are “protected by safes, cages, sealed containers, locks, and keys.” The progress of a registered mail item is typically tracked differently (and more diligently) and the recipient has to provide a signature on delivery.

So, this envelope would have been carried in a separate container (likely a locked mail pouch) with other registered items. Postal clerks along the route entered the letter’s progress into their own ledgers to create a record of its travels. They would create an entry for each registered item to indicate when they handled the item and they often included a record of how it had gotten to them and where it was sent to next. A number corresponding to the ledger entry was typically placed on the mail item to create a paper trail if something untoward happened and there was a need to figure out what had gone wrong.

It was a bit like traveling first class in an airplane. This letter simply got more attention during its journey than a standard letter did.

If a person were to send a registered item today, they might declare that it had a particular value. In doing so, they could also purchase some insurance through the post office in case something happened to the letter. In this case, the mailer indicated that the letter had “no value,” and a docket stating that fact was placed on the envelope.

There might be a few reasons why this letter was registered that had nothing to do with value. But since there are no contents with the envelope, anything I suggest would only be speculation. So, I will leave it to your imagination. Pick any reason you can think of that a person might want to pay for registrations services and you can make it your own personal narrative for this particular item!

There are two additional British markings that indicate that this letter was registered. The Lombard Street marking was applied at the point of mailing. However, this letter was going to need to go to the Foreign Mail Office in London because it was a recognized exchange office for mail with the United States.

The clerks in the Foreign Mail Office also wanted to indicate that this letter was registered. It may seem like a second marking is redundant, repetitive and otherwise unnecessary. But, we need to consider that the postal clerks in the United States would be looking for certain British markings to tell them that the letter was, in fact, a registered item. If those markings weren’t there, it is possible (though unlikely) that they wouldn’t recognize that this item should be given registration services.

Remember, postal markings were used as signals to postal clerks down the line that would handle the letter along its travels. These markings could indicate if a letter was fully paid or not. They could also tell future clerks that it was registered and they could indicate how the postage could be divided between postal services.

What Did it Cost to Send?

The postage cost for a letter from the United Kingdom to the United States in 1864 was one shilling for a simple letter that weighed no more than 1/2 ounce. The cost for registration for an item with no declared value was six pence. And, happily, the postage stamps match up nicely with the costs.

I recognize that many who read the blog will not be completely familiar with the monetary systems of the time. For the British, twelve pence was equivalent to one shilling. So, 1 shilling and 6 pence is the same as 18 pence. Also, one British penny was equivalent to 2 US cents. That makes a shilling equal to 24 cents and the total cost in US money for this letter was 36 cents (18 pence x 2).

There are a couple of instances where the number “27” shows up on the cover. These could certainly be ledger numbers for registration, but I think it is more likely that these markings were intended to indicate how much of the postage was to be passed to the United States.

Twenty-seven cents would be the correct amount to pass to the US to cover the costs of US surface mail (5 cents), the cost of the Atlantic crossing (16 cents) and the US portion of the registration expense (6 cents). The registration fee was to be split evenly between the two participants (US and UK). This tells us that the British were expecting to keep 9 cents (3 cents surface and 6 cents registration = 4.5 pence).

Crossing the Atlantic

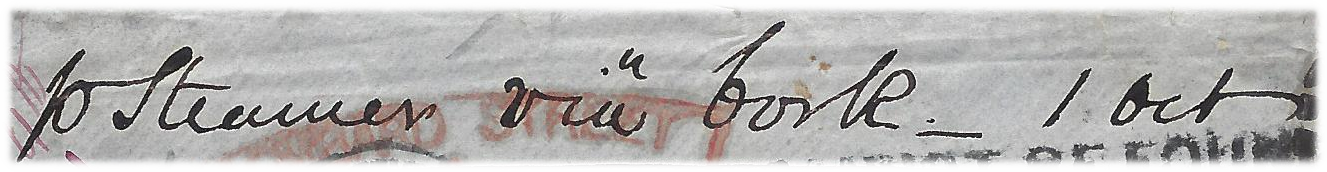

The docket at the top of this cover actually corresponds with the Cunard Line ship that was scheduled to leave Liverpool on October 1 and then Cork (Queenstown) on October 2. The Europa would arrive in Boston on October 14 and the mailbag or pouch for mail to New York would be sent on to their foreign mail exchange office.

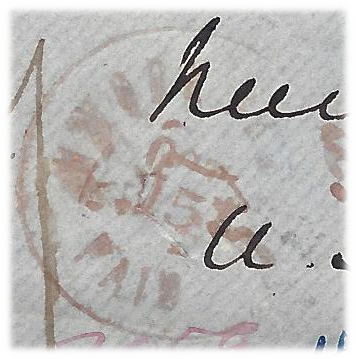

The letter was taken out of the mailbag the next day in New York City and a red marking was applied to the envelope. This marking typically tells us whether the ship that carried the mail had a contract with the British or the United States. If you look carefully, there appears to be the letters “N. York Br” which would correspond with a British packet - which agrees with the Cunard sailing.

So, I think it is clear that this letter traveled on the Europa and that the 16 cents for the Atlantic sailing belonged to the British, not the United States.

Well, sometimes not everything works out. The “27” credit markings would be correct for a mail sailing that was a US contract, not a British contract. With a British Ship, this number should have been “11” and not “27.”

I guess mail clerks were human too. Or, perhaps I am the one who made a mistake? It’s a good reminder that we’re dealing with things that can be inexact and in error. My sense is that I have the interpretation correct and that a mistake was made in calculating the credit amount. But, I am also willing to accept that I can be wrong.

Maybe I’ll write an update in the future with more information?

Advertising Mail in the Newspapers

And now it gets interesting.

The letter is addressed to Alexander Ellis Ford at the Fifth Avenue Hotel in New York. Apparently, Ford was not there when the carrier attempted delivery so it was taken back to the post office.

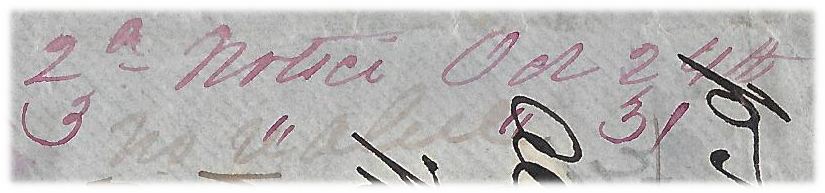

The next step for attempting to find Mr. Ford was to advertise the letter’s presence in the New York post office in a local paper. It was a common practice for mail that had not been picked up at the post office to be advertised once. But, since this letter was registered, it was actually advertised not once, but three times!

October 31st was the final time this letter was advertised. However, it remained in the post office just in case Mr. Ford or his representative would come calling for his mail.

I’ve enjoyed tracking letters that go on a “merry chase,” traveling the world in an effort to chase down the addressee. In this case, the chase goes nowhere. Instead, the letter arrives in New York on October 15 and it sits in the post office until November 28.

Hey! If you don’t have any knowledge about where else the Mr. Ford might be, it doesn’t make sense to send the letter away in an effort to find him. Instead, you put out a beacon in the form of advertisements in hopes that he would pick up the newspaper and read that he has mail waiting for him.

Clearly it didn’t work. Maybe Mr. Ford wasn’t even in New York at the time the letter got there.

The end of the search for Mr. Ford

Postal regulations provided guildelines for how long this slow motion chase would continue until it was time to give up. In this case, the search ended on November 28 and the letter was marked with the indication that the addressee “cannot be found.” As a matter of fact, there is also a hand written notification on the back of the envelope.

It’s at this point that the letter went to the Dead Letter Office. Any item going to the DLO was classified as follows:

Letters that remained at the post office unclaimed (typically after one month).

Letters that were deemed unmailable because the address could not be deciphered, was incomplete or the content was deemed to be "obscene."

Letters where no attempt to pay postage was made (or someone tried to re-use a postage stamp). These were classified as held for postage.

Packages over 4 pounds in weight

Letters refused at the post office by the recipient.

This item falls under the first category because the addressee “cannot be found.”

Since this letter originated in the United Kingdom, it had to be returned to the Returned Letter Branch in London, England.

Some brief searching finds that there are letter records of Alexander Ellis Ford in Newfoundland at the time. He was in correspondence with his father, James Ford, in London. Since this letter was registered, it was easier for this dead letter to find its way back to the writer. Therefore, it seems safe to conclude that this letter did find its way back to the James Ford after it’s merry chase was over.

Thank you for joining me and I hope you have a fine remainder of your day and a good week to come.

Additional Reading

If you haven’t had enough, here are some additional related entries you might enjoy:

Humbug - PHS #165

Merry Chase - PHS#57

Not Called For - PHS#81

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack. And, some publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest.

Thank you, Rob.