Much Ado About Adae

Postal History Sunday #202

Welcome to Postal History Sunday!

It seems like the weeks just fly by in May and June at the Genuine Faux Farm (our small-scale, diversified farm). For those of you that garden, you probably have an inkling as to how much time and energy must be put into planting, cultivating and doing the work that includes vegetables, fruit trees, laying hens, hen chicks, and turklets. While we have significantly scaled our farm back since 2020, there is still plenty to do - and it gets more difficult when there are off-farm jobs and a bit more rain than we’re comfortable with.

Still, we’re doing okay and we’re not struggling with flooding like some of the folks in northwest Iowa and the surrounding parts of South Dakota, Nebraska and Minnesota.

I told you all of that just to give you an update on us and to explain why it feels like the past couple months of Postal History Sundays seem to be sneaking up on me more than is usual. Still, here we are! With a new PHS for you all to enjoy. So put on the fuzzy slippers and grab a favorite beverage. Let’s see if we can learn something new!

Today I am going to start us off with an envelope (a cover) that has the distinction of being in my collection longer than most. Before we get into it too much, there were two particular attractions that interested me at the time.

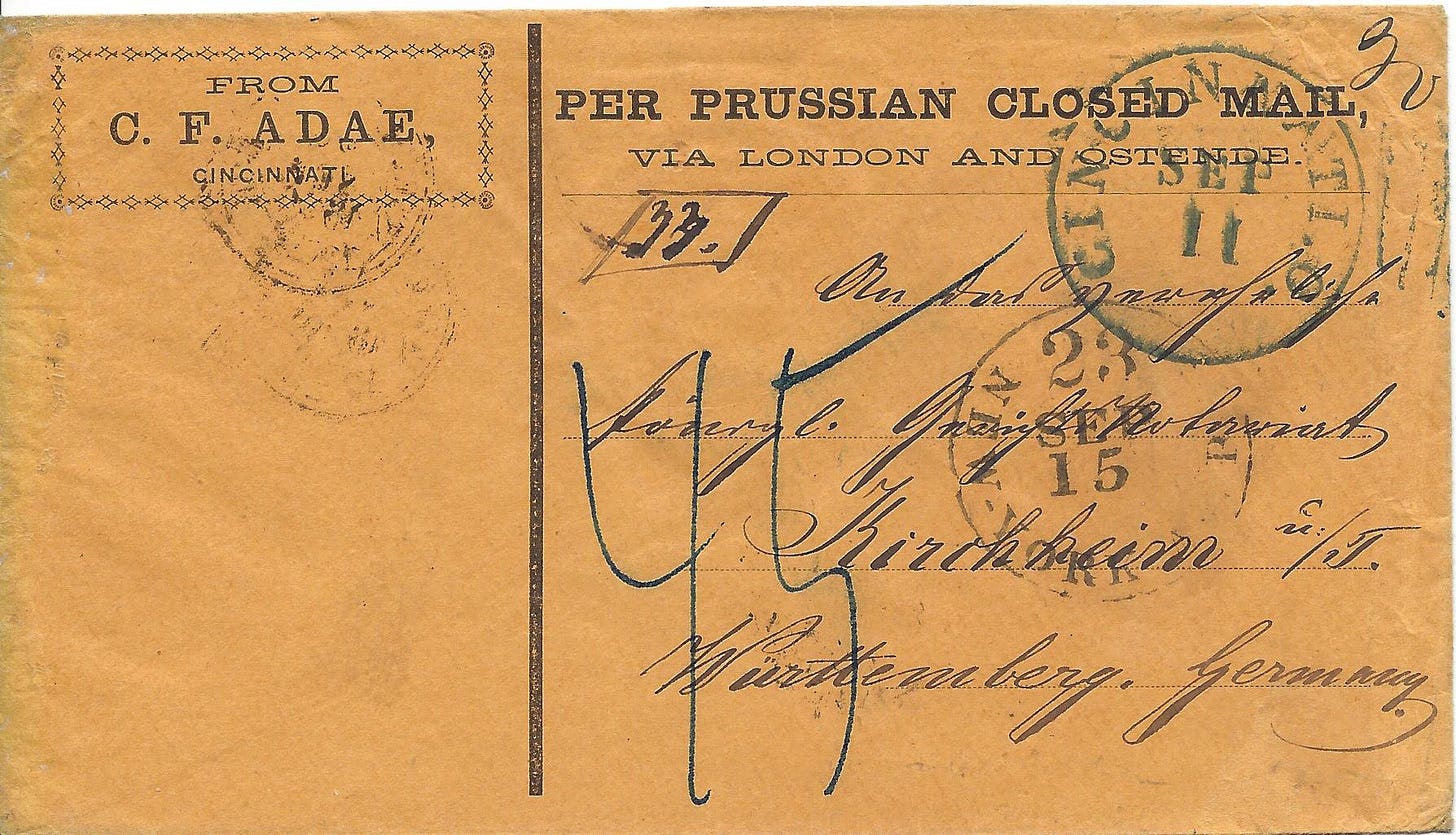

First, and foremost, this cover bears a 24-cent 1861 design postage stamp (the stamp that is affixed sideways on the envelope). Up to this point, the only covers with this stamp in my collection traveled from the United States to the United Kingdom. This is not a surprise because the 24-cent stamp was issued with the primary purpose of paying the simple letter rate for mail from the US to the UK. This cover, however, went to Wurttemberg, one of the German States. The postage rate for a simple letter to Wurttemberg was 28 cents if it went via the Prussian Closed Mails. So, there are two 2-cent stamps added to the cover to pay the proper postage rate.

The second attraction, at that time, was the origin. I have long been a Cincinnati Reds baseball fan and finding a letter in the 1860s that traveled to a country across the Atlantic from Cincinnati appealed to me. While I might have been even more enamored with an item from Iowa, the Cincinnati origin was enough to get me to borrow from my “future hobby budget” to get it.

A Quick “Read” of the Cover

Every so often, I try to step everyone through how I “read” a cover so you can see the process of discovery I take when I try to figure out how it got from its origin to its destination. Last week, I showed an item that went to England and this week we’ll look at this one to Wurttemberg.

We’ll start with the postage stamps that provided evidence that the letter was prepaid for its travels to Wurttemberg. The postal clerk in Cincinnati used a cancelling device with blue ink to deface the stamps in an effort to prevent the stamps from being re-used.

Wurttemberg was a member of the German-Austrian Postal Union (often shortened to GAPU or DOPV for the German speaking). Prussia, another German State and member of the GAPU, had a postal agreement to exchange mail with the United States. As a result, mail patrons in Wurttemburg could receive items from the US via Prussian Closed Mail. The cost of that mail was 28 cents per 1/2 ounce in weight (effective Sep 1861 to Dec 1867).

The letter was in Cincinnati on March 24 and it found its way to the New York Foreign Mail Office. Any letters going to a foreign destination were required to get to one of the US post offices that had been identified as an exchange office with Prussia. New York was one such office and it was received in time to be placed in a mailbag for a sailing across the Atlantic.

The round, red marking shown above is the New York exchange marking which reads “N. York Br. Pkt 7 Paid.” This tells us that a ship under contract with the British Post Office was going to carry this letter (Br. Pkt). It also tells us that 7 cents of the 28 cents collected were going to be passed to the Prussian Mails.

The square, blue marking reads “Aachen 11 4 Franco.” This tells us the letter was taken out of this mailbag on April 11 in Aachen at the border of Belgium and Prussia. Aachen was an exchange office for US mail from New York and this shows the letter was processed and it was acknowledged as fully paid with the word “franco.”

This, by itself, is enough information for us to determine that the letter was carried on the Cunard Line’s Africa. It actually left Boston on March 29 - which means it left New York on March 28 to get to Boston for that ship’s departure (something we might talk about in a future PHS).

The Africa arrived at Queenstown (Cork, Ireland) on April 9. The letter traveled from there to London. It then crossed the English Channel to Ostende, Belgium, where it boarded a train to cross that country. During this entire trip the letter stayed in the mailbag with other letters destined for the Prussian Mail. It would not be taken out until it reached the Prussian clerks at Aachen on April 11.

An interesting thing about this cover is that the sender had preprinted envelopes that made it clear this letter was intended for the Prussian Closed Mail. It also makes it clear that the expected route for this mail was via London and Ostende. This is a good clue that there might be something more going on here because routing dockets are often hand written. If someone in the 1860s bothered to have preprinted envelopes for letters to Germany, they must have had some real need to send mail that direction!

We’ll get to that later… For now, let’s look at the back of the cover.

The back of the cover includes four more postmarks applied in Germany. As I started working with it, I realized this is an older image that I created many years ago. Alas! So, the arrows for the Stuttgart and Klein-Sussen marks are switched. But, we can still conclude that this letter got to its destination (Donzdorf) on April 12. Perhaps I will break this part of the journey down further in a future PHS!

You might have noticed that I have not (yet) told you which YEAR this letter was mailed. I felt this might be a good time to illustrate that the year of mailing is not always perfectly clear after a perfunctory viewing. If you look at the front of the cover you will find that none of the postmarks have a year as part of their dates. There are no dockets that give us a year date either.

Well, I happen to know that the 2-cent postage stamps featuring Andrew Jackson was not issued until July 1, 1863. So, the letter has to be sent after that point in time. We also know (because I mentioned it earlier in the blog) that the postage rate was effective from Sep 1861 to Dec 1867. So, it is very unlikely to be later than 1867. Happily, more than one of these transit markings on the back include the year (1865), so we don’t have to work much harder to figure it out.

If we were not fortunate enough to have postmarks with the year date, we would be left looking for trans-Atlantic mail sailings that match up with the exchange marking dates (Mar 28 and April 11) for the years 1864 through 1867. When I followed through with this exercise, I got even more good news! The sailing dates for the Africa match up with the 1865 year date identification.

Who was C.F. Adae?

I mentioned earlier that the sender of our first letter must have had cause to send many letters to the Prussian Mail because they had envelopes printed for that purpose. If you look at the top of that envelope, the sender is identified as C. F. Adae of Cincinnati. That, of course, begs the question, who was this C. F. Adae and why did he have preprinted envelopes for mail they sent?

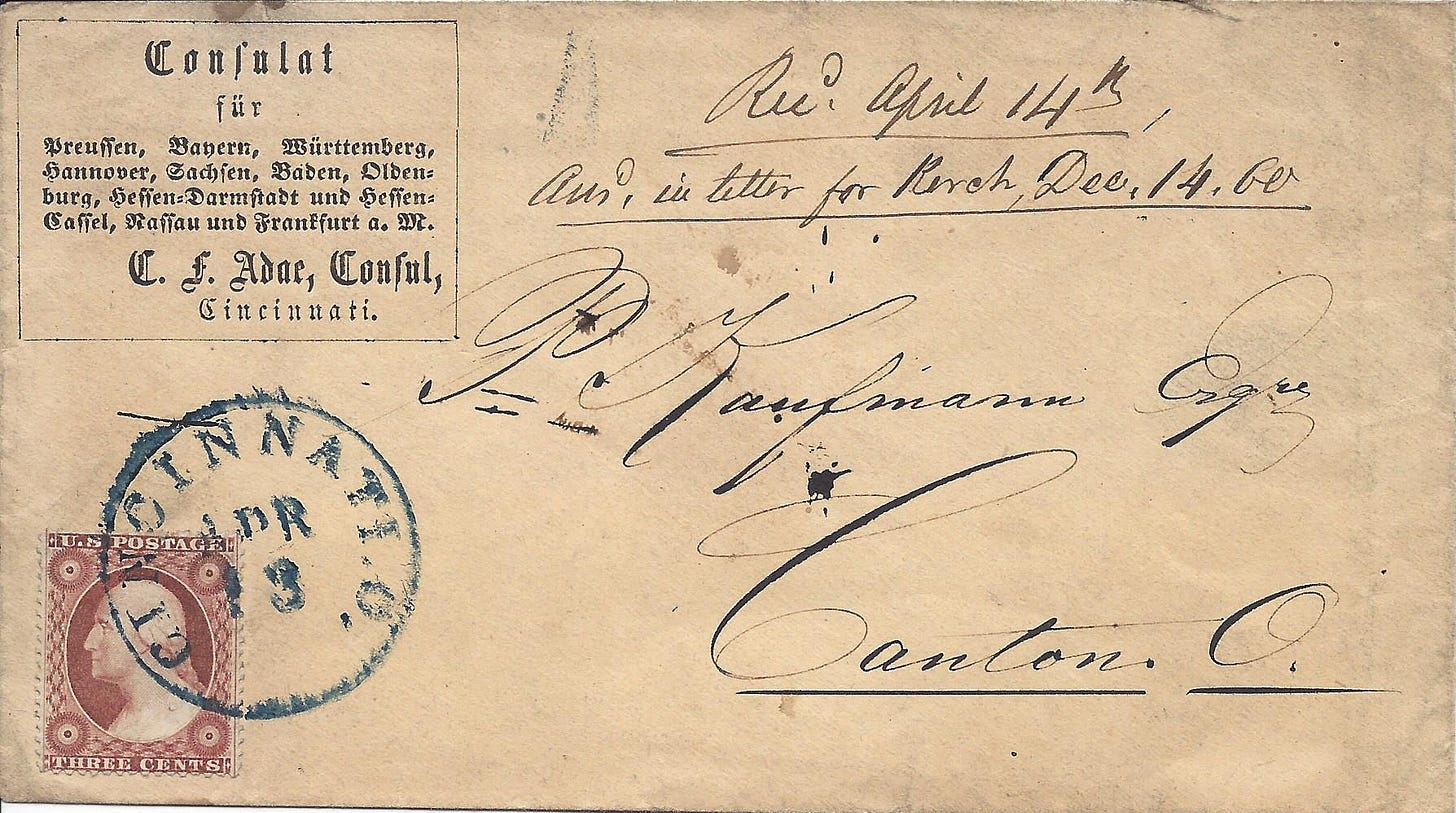

To help answer that question, I show you a second cover (another envelope) that was mailed from Cincinnati to Canton, Ohio, in 1861. This letter bears a 3-cent stamp to pay the internal US postage for a simple letter. The Cincinnati postmark tells us it was mailed on April 13 and a docket at the top indicates that the letter was received on the 14th.

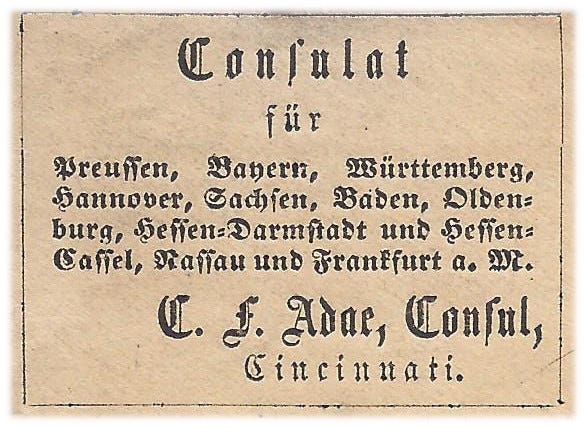

The real highlight is the design at the top left of the envelope, which is shown below:

This preprinted design at the top left of an envelope is a type that is often called a corner card. This particular example advertises C. F. Adae’s services as a Foreign Consul for several German States, including Prussia, Bavaria, Wurttemberg, and many others. Consulates were, and are, semi-official agents who provided services for persons traveling or who have emigrated from a different country. So, C. F. Adae offered support to persons from these German States who might need financial, legal or other support while they were in the United States. In the present day, Germany has consolates in several US cities.

This second letter is addressed to a person with the name of Kaufmann in Canton. It’s not difficult to presume that Kaufmann had German roots and had reason to avail himself of Adae’s services.

Carl (or Karl) Friedrich Adae (1815 - 1868) was born in Wurttemberg and moved to the US in 1833. He started a business investing in imports and exports of sugar, liquor and tobacco. He served as a consul for some German States as early as 1847, eventually providing the service for all German States until his death. The most common service he provided as consul was access to money exchanges to and from Europe. In order to facilitate that service, Adae opened a banking business.

A bibliographic work exists (in German) that was written by Richard E Schade in 2003 if you have interest in learning more. Since I do not read German, I have not checked that work out. However, I have been able to find some translated snippets from that work that give me some of the details.

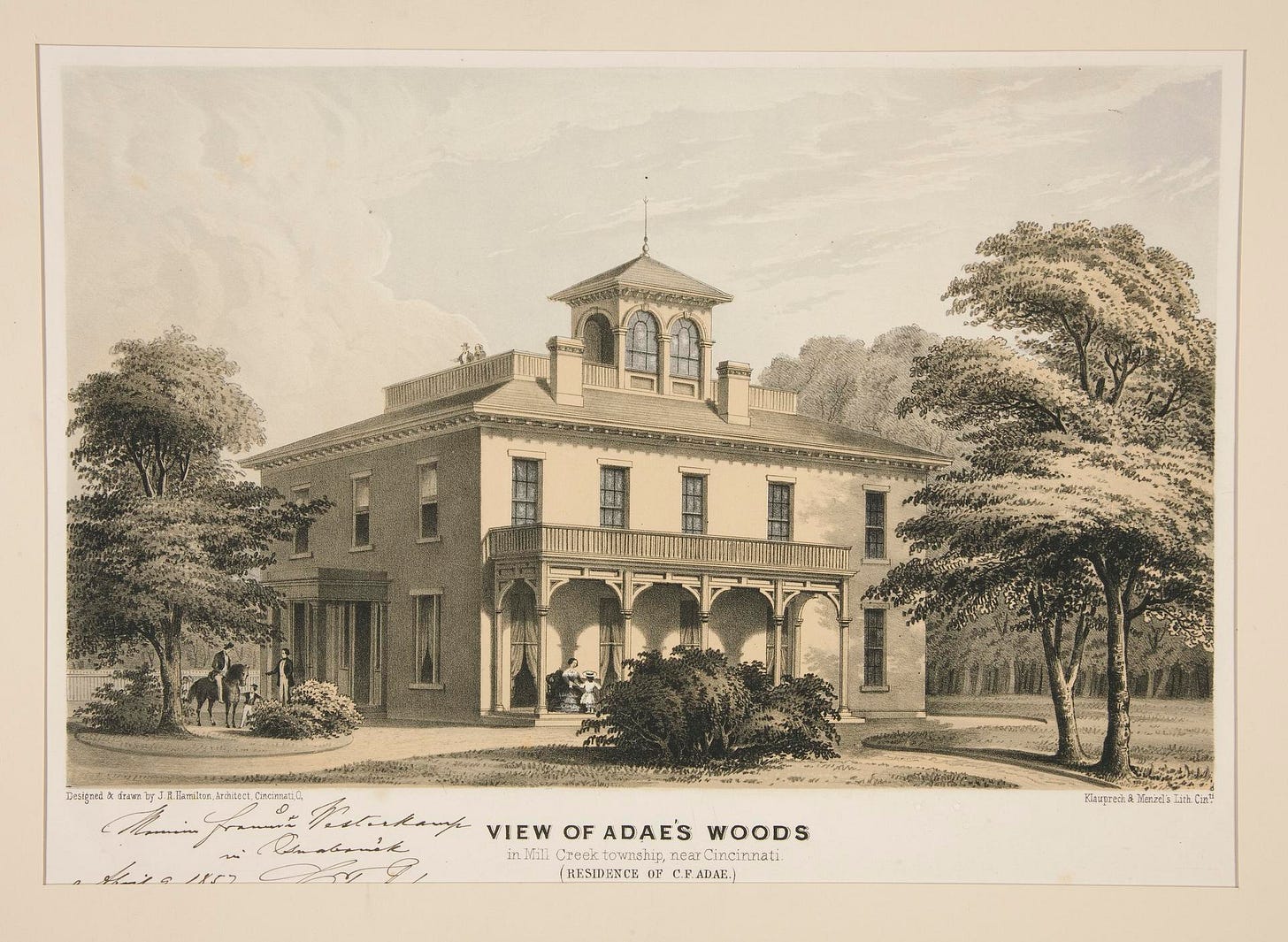

Adae was apparently quite successful, if we consider the image (shown above) of the homestead he had built in the 1850s near Cincinnati. A nephew, Carl A. G. Adae became president of C. F. Adae and Company and became German Consulate in 1871. Unfortunately, Carl A. G. was either not as savvy as his uncle or they had fewer scruples since they were arrested for bank fraud. Knowing that the bank was going to be insolvant in December of 1878 they still accepted deposits. As a result, these deposits were paid back at 30 cents on the dollar after legal challenges.

An Unpaid Letter from C. F. Adae

That brings me to a third letter from the office of C. F. Adae in Cincinnati. This letter was mailed in 1860 and was sent unpaid to its destination in Wurttemberg.

We know this letter is unpaid because there are several clues that tell us (and the German postal clerks) that it is unpaid. First, there are no postage stamps on the envelope. While that does not necessarily a definitive indication that it was unpaid, it is a good first clue. Second, there are no markings that read “paid” or “franco.” And third, the New York exchange marking was applied using black ink instead of red.

There is an ink “45” written boldly in the center of this envelope that indicates that the postal carrier should collect 45 kreuzer from the recipient at the point of delivery. The New York exchange marking has a bold “23” that tells the Prussians that the US expects the equivalent of 23 cents in postage as part of their share of the expenses to get the letter to its destination.

This envelope clearly shows an embossed design advertising Adae’s services as Consulate for Wurttemberg. Between the preprinted designs and the embossing, it is clear that C. F. Adae had a great deal of correspondence to clients in the US and in Wurttemberg. It would be interesting to see if there are similar envelopes that show embossing touting his consular services for other German States.

Well, that certainly was a lot of ado about Adae! Thank you to everyone who voted via comments, social media and email on the topic for this week’s Postal History Sunday. It was a close race, with Adae winning by a whisker.

In other news - Postal History Sunday just crossed the 200 subscriber number just prior to the 202nd entry. Thank you all for your support! Our next goal is to reach 250 subscribers before our 250th entry. I think we can manage that.

Thank you for joining me today. Have a fine remainder of your day and an excellent week to come.

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack. And, some publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest

C F Adae was also General Agent for the Hamburg & Bremen Steamship per Williams Cincinnati city directory of 1868.

Whether agency for the said steamship co was for logistics of merchandise or immigrants, I don't know.

By the way, by the 1860's 30% of Cincinnati's population was either German immigrants or of German descent.

Congratulations on 200+ blogs and subscribers! I think it would be interesting to hear more details on how, 159 years later, you actually can find out the name of a specific ship that carried a specific letter, and how you can find a detail such as that letter actually left from Boston not NY.