Welcome to Postal History Sunday! Everyone is welcome here, regardless of your interest or knowledge of postal history. I’ll do my best to keep things accessible and interesting while I explore things that I enjoy. Meanwhile, feel free to grab a favorite beverage and a snack. Put on those fuzzy slippers and get comfortable and let’s see if we can all learn something new.

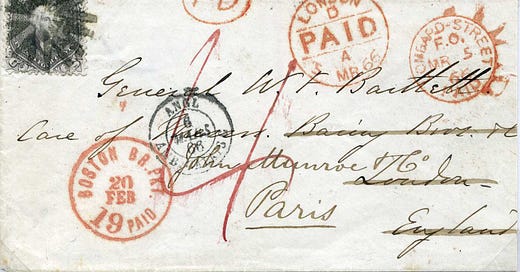

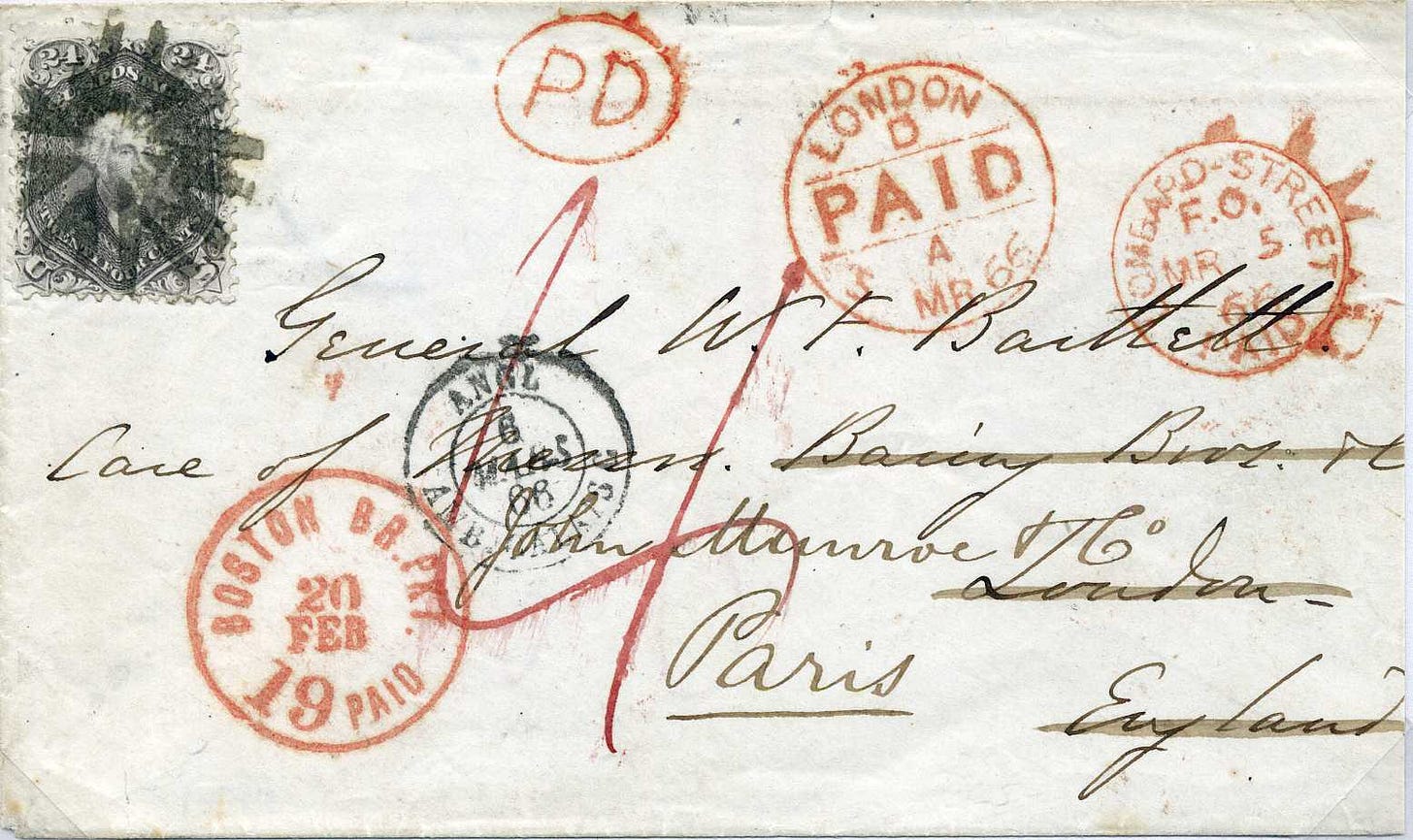

This week, I wanted to return to the subject of how I "read" a cover so I can learn how it got from here to there. To do that, I offer up this piece of letter mail from 1866 that was sent from Boston to London for a General W.F. Bartlett. He apparently was not in London at that time so the letter was forwarded on to Paris.

The Letter Enters the U.S. Mail System

The postage rate in 1866 was 24 cents for a letter being mailed from the United States to the United Kingdom (England, Ireland, Scotland, Wales) for any letter that weighed no more than 1/2 ounce. A piece of letter mail that falls under the first weight increment is often referred to as a simple letter.

The 24 cent stamp showed that the sender had paid the postage required. The postal clerk used a handstamp and black ink to deface the stamp and prevent it from being used a second time. Postal historians and philatelists call these cancellations or obliterators. Some post offices used devices to cancel the stamp that had different designs - like the circle of V's shown here. Some collectors would call this a fancy cancel.

Some collectors love to pay attention to the amazing breadth of cancellation designs that have been used over the years. In fact, there have been people who have taken upon themselves to study and catalog all of the known postal markings for specific locations or time periods. For example, the book titled "Boston Postmarks to 1890" by Maurice Blake and Wilbur Davis confirms that this particular cancellation was used in Boston at the time this letter was mailed.

If I had to take a guess, I would say that the letter was dropped at the main Boston post office where the foreign mail exchange office for that city was housed. That could explain the absence of a city postmark in black ink that would normally accompany the cancellation on the stamp.

The U.S. Exchange Office

If a letter was destined to leave the United States, it had to go to a post office that was designated as an exchange office for the destination country. In 1866, the year this letter was mailed, Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, Detroit and Portland (Maine) were all designated as exchange offices for mail departing to the United Kingdom. The foreign letter office at these locations would place an exchange marking on the envelope like the red Boston postmark on this piece of mail.

An exchange marking often provides us with all kinds of interesting information. In this case, I can see:

A date that tells us when the letter was scheduled to leave Boston (Feb 20)

Br. Pkt. (British Packet) tells us the ship that would cross the Atlantic was under a contract with the British Post Office.

The letter was PAID in full.

19 of the 24 cents of postage were to be passed on to the British postal system.

That certainly is a good amount we can learn from one circular handstamp in red ink! And, speaking of red ink - that was another indicator that the item was fully prepaid. If the exchange marking were applied in black ink, it would alert the receiving foreign exchange office that there would be postage due from the recipient.

Once this marking was applied in the Boston Foreign Mail Exchange Office, the letter was placed in a mailbag that would be destined for the ship (or packet) once the mail collection period closed. The bag would be closed securely - not to be opened until it arrived at a corresponding exchange office in the destination country.

Crossing the Atlantic

Postal historians nowadays are fortunate that we have reference books to help us find some of the information that would once have required digging through numerous old newspaper archives to find. I will be forever grateful for the efforts of Walter Hubbard and Richard Winter and the book, North Atlantic Mail Sailings: 1840-1875. It is because of their work that I can tell you this letter left Boston on February 20 for New York City. At New York City, it was placed on the Cunard Line's Australasian, which left on its trans-Atlantic voyage February 21st.

While the Australasian did run on steam, it was also outfitted with masts and sails as a failsafe. If the steam engines failed, the ship could still get to its destination.

Several things have changed since Hubbard and Winter worked on their excellent reference book. Among them has been improved access to old newspaper archives via the internet. A person is no longer required to find a library with microfiche copies of newspapers in order to view many of the more popular periodicals. The New York Times, for example, is quite accessible via their Times Machine.

The Times typically included Marine Intelligence on page 8 that listed ships leaving and arriving at the port of New York. The major shipping lines also took out advertisements, like the one shown above. Because of the work by Hubbard and Winter, I am able to go about the process of confirming information rather than digging around to find it - or not.

The British Exchange Office

If you guessed that London might be a British exchange office for mail from the United States, you get a prize!

Ok. It was a pretty easy guess, I know. But good for you nonetheless.

The mailbag arrived in the London Foreign Letter Office and was opened by the clerks there. As each letter was processed, it received a London exchange mark with a date that indicated the day the bag was opened. There were actually a few different exchange postmark designs in use during the 1860s, but this one is fairly common for 1866.

At this point, the mail would be sorted to go to its various destinations in the United Kingdom. This letter was due to be taken to the Baring Brothers - a large financial institution in London that often provided banking and mail forwarding or holding services for travelers.

Baring Brothers Serving as Forwarding Agent for Mail

The Baring Brothers were actually part of a fairly recent Postal History Sunday titled There and Back Again. But, as a brief recap, many financial firms provided services for travelers in Europe, such as banking services and mail holding or forwarding.

Putting it simply, a traveler would pay for this service and it would give those who wished to contact them an address where they could send their mail. It was then up to the forwarding agent (the Baring Brothers in this case) to either hold on to the mail until the traveler came to the offices to pick it up OR send it on to a location left with them by the traveler. That location was often with ANOTHER firm that also providing mail forwarding or holding services, as well as banking.

It is not hard to imaging that General W.F. Bartlett may well have left an itinerary with the Baring Brothers with instructions for mail forwarding as he traveled. Apparently, the instructions on March 5 was - "please send it to me while I am in Paris."

British Exchange Office with France

Baring Brothers had their marching orders for any letters to the General. So, once they had sorted out the mail they had received for their clients, they probably sent one of their people to the post office to re-mail everything that was to be forwarded.

The Lombard Street post office was probably a ten minute walk from the Baring offices in the Bishopsgate sector of London, so it wasn't all that far away. And, it just so happens that the Lombard Street post office could serve as an exchange office for mails to and from France. If you look closely at the marking above, the letters "F.O." stand for "Foreign Office."

Apparently, the Baring Brothers did pay the postage, even though there are no stamps to show the payment. Instead, this red circular marking AND the red "4" on the front indicated payment - and the amount of the postage required.

Mail from the United Kingdom to France cost 4 pence for each 1/4 ounce in weight (7.5 grams). This rate was effective from Jan 1, 1855 to Jun 30, 1870.

It is interesting to note that the mail between the United States and the British system was rated as 24 cents for the first 1/2 ounce. So, it would have been very possible for someone to send a letter that would have qualified for a single letter that traveled overseas, but then possibly be a double weight letter from the U.K. to France.

Further evidence that this letter was paid in full for its new destination in Paris is the PD in an oval that appears at the top.

The French Exchange Office

By now, you are likely getting the hang of this. The letter had been placed in a mailbag at Lombard Street with other mail bound for France. The bag remained closed as it crossed the English Channel and was opened when it arrived at the French exchange office.

The marking placed on the letter is shown above and it reads "Angl. Amb. Calais G (or C) 6 Mars 66."

The "Angl." simply means it was mail received from England and the date was March 6, 1866. The "Amb. Calais" portion shows us something different than the other exchange markings. It turns out that this marking was applied while it was on board a mail car on the train from Calais to Paris. The mail convention between the French and British identified this train as an exchange office so mail could be sorted even before it reached Paris.

The back of this item has a single, weak marking that shows it arrived in Paris on the same day (March 6). This last marking would have been applied by the Paris post office to indicate its arrival at the destination.

John Munroe & Company - Paris

John Munroe & Co was a banking firm that was established in New York and opened a subsidiary in Paris during the year 1851. They specialized in transactions between the French, British and Americans, which made their company a logical choice for a traveler from the United States.

This time around, it seems as if the letter was held for General Bartlett until he picked it up in Paris. We cannot be certain that this is the case, because there is no docketing or letter contents to confirm this guess. But, it is the simplest choice and is supported by other, outside documentation.

And Now… for a Quick Summary

I realize that sometimes it gets difficult to follow when I take small portions of the cover and highlight them. So, shown above is a full slide that points out the Boston and London exchange markings. These show us the points in time when the letter was put into the mailbag in Boston and taken out of that bag in London. This is the service that was paid for by the 24 cent postage stamp.

The second slide shows us the markings that apply to the trip from London to Paris. The red “4” indicates that four pence in postage was paid in cash by Baring Brothers to get the letter to Paris.

Now you’ve got two places to look at where everything is. It’s just proof that I do listen to suggestions… I even act on those suggestions every so often!

General William Francis Bartlett's Travels

William Francis Bartlett (June 6, 1840 – December 17, 1876) turns out to be a fairly easy individual to track down in the annals of history. The Memoir of William Francis Bartlett by Francis Winthrop Palfrey was published in 1878 and is available for free at Hathi Trust. For those who might become interested in his story, I suggest you go there. I, personally, have only skimmed portions of the content as I was looking for specific information. I may read more at a later point in time if I decide to do more with this story.

Bartlett was wounded multiple times during his service with the Union in the Civil War, losing his leg fairly early in the conflict. Despite this loss, he returned to duty and climbed the ranks, despite having to rely on a prosthetic leg to replace what he'd lost in battle. He was captured in 1865 when his prosthetic was hit by some sort of opposing fire and he could not retreat with his men.

He was still technically on active duty in 1866, but his command had been "mustered out" (dismantled). Apparently, he was able to secure leave from then Secretary of War Stanton so he could travel in Europe for six months. The beginning of his letter is shown below, but the entirety is presented starting on page 168 of his Memoir.

To make the story shorter, leave was granted, probably without pay, and Frank Bartlett was allowed to leave the country and travel Europe.

At the time this letter arrived in London (March 5), Bartlett has begun a tour of southern France and Italy, not staying in any one location for terribly long. He even visited Garibaldi in the latter's home briefly. He returned taking a route via Switzerland, visiting Geneva along the way.

Because of his transitory nature at this time AND the fact that he was not conducting business other than that of a tourist, it is highly likely mail was held for him in Paris. An alternative, of course, is that a courier carried a packet of letters to some location at a mid-point in his travels, but there can be no proof of that unless there are hints in the Memoir.

Have a fine remainder of your day and an excellent week to come!

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack. And, some publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest.

Well it has become Postal History Friday for me this week, thus the belated thank you. Thank you, also, for including the information on the ships that carried the mail. I know that isn’t the primary focus, bur I alao wnjoy all things ship-wise.

Rob, this is an amazing article. I have a very similar cover and didn't understand the exchange markings. Your article was very enlightening. I was aware of Substack and have considered using it. Your transition from Blogger is impressive.