Remembrance and a Merry Chase

Postal History Sunday #197

This week, in honor of Memorial Day in the United States, I will break with tradition and not tell you how to pack your troubles away so you can enjoy a few moments reading this blog. Instead, I'm going to be presumptuous and tell you to push your own personal troubles out of the way so you can ponder what it means for individuals to die in military service or for people to be injured, displaced, and terrorized by war.

But, even as we ponder, I hope we can also learn something new and still enjoy as we explore the postal history hobby. So, this week, I’m going to share something that can serve as a remembrance for Memorial Day while also providing you all with a Merry Chase.

Many postal historians study and collect items that illustrate the process of mail delivery during periods of conflict. Mail services often had to innovate and modify how they went about getting letters, parcels and printed matter from one place to another. On top of that, war displaces individuals from their homes to serve in the military or to leave areas of conflict. This leads to a high likelihood that letters must make a few detours before finally finding the intended recipient.

That’s where the Merry Chase often comes into play.

By now, you also know that I like a piece of postal history that leads me to a good story. When it comes to stories, wartime can provide numerous compelling plot lines that feature “normal, every day people” - rather than the rich, powerful, or famous.

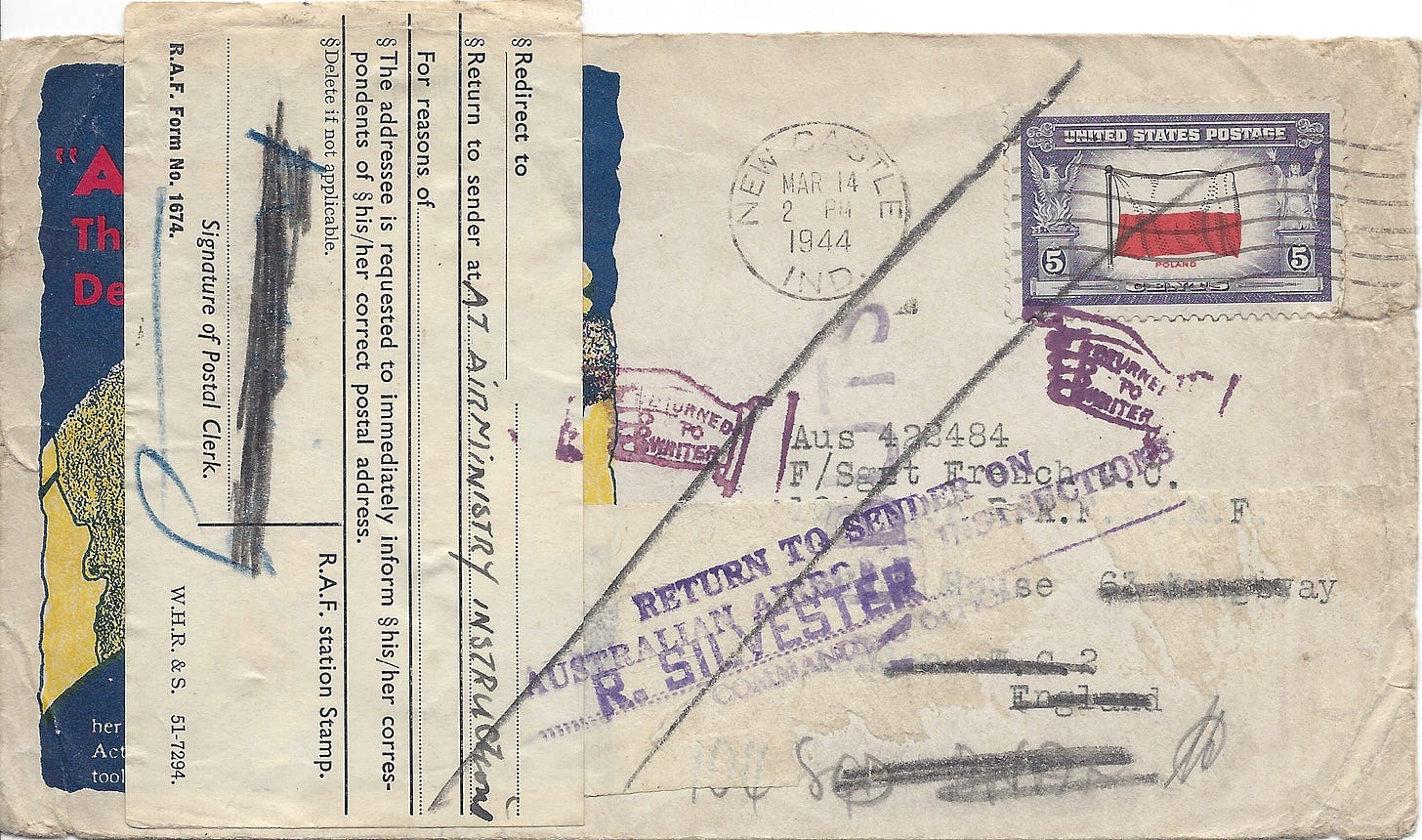

At the time this letter was mailed, the cost of mailing to a foreign destination from the United States was 5 cents for every ounce in weight. A five cent stamp from a series known as the "Overrun Countries" was applied to pay the postage required.

A Colorful Envelope to a Relative in the Armed Forces

H. (Horace) Edgar French, of New Castle, Indiana, sat down to write a letter to Flight Sergeant Geoffrey French of the Royal Australian Air Force. The Flight Sergeant was on active duty in Italy at the time. However, letters for R.A.A.F. members in Europe were addressed to the headquarters in London so that they could properly forward the mail using military postal services. Obvioiusly, the actual locations of members of the armed forces was not made public for people like H. Edgar French in New Castle to send mail directly. So, someone had to be ready to forward mail as units moved around.

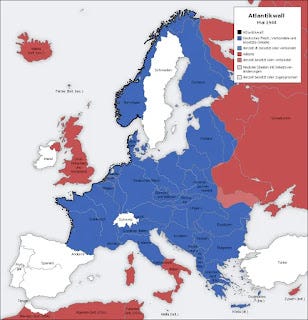

Edgar posted this letter on March 14, 1944. It was still a few months until D-Day and the Normandy invasion. So, Germany occupied all of France and most of mainland Europe. Italy, on the other hand had signed an armistice with the Allied forces in September of the prior year with the fall of Mussolini. But, of course, the Germans had now moved into northern and central Italy.

I have not determined how these two individuals were related, but it seems clear that they must have been. There were no contents with this envelope, so who knows what Edgar wrote about? It could have been stories about a favorite niece or reports on the family's Victory Garden. Maybe he talked about pianos and made references to a visit to Australia.

That's something I'll never know. But, there is enough information out there to start filling in some blanks - which is something we’ll do more of later!

Like so many people at that time, H. Edgar wanted to advertise his support for the Allied Forces and used an envelope that showed a patriotic design (known as a cachet) that heralded the Lease-Lend Act in the United States. A label now covers that design, but I was able to move the label (leaving it attached) so I could scan it and share it with you here.

The Lease-Lend Act is more commonly referenced as the Lend-Lease Act (but who's quibbling?). This legislation provided President Roosevelt with the authority to send materials, such as food, supplies, and weapons, to Europe without breaking the United States' neutral stance during the early years of the second world war. The legislation went into effect on October 23, 1941, about a month and a half before the attack at Pearl Harbor and the end of that neutrality.

Obviously, the Lend-Lease Act wasn’t quite as poignant in 1944, when this letter was mailed. But, I suspect, Mr. French had a pile of fancy envelopes that he needed to use.

For those who have interest, there are people who study the myriad designs and printers who created patriotic envelopes during World War II and the definitive book on the subject was written by Lawrence Sherman. Sherman’s book is a catalog reference work and might not be as interesting to those who are merely passing curious about the topic. However, for the cost of ten dollars, you can download a copy to view and decide for yourself, thanks to the Collectors Club of Chicago.

The envelope design for the letter I am featuring today is #423 in Sherman’s book.

This particular envelope was printed by a company called Advertisers Press which operated out of Des Moines, Iowa. With only a cursory search, Advertisers Press appears to have been a smaller operation and they, like many print shops of the time, performed a wide range of print jobs. For example, here is a 1944 publication of two lectures on the war by Eric Mann.

Advertisers Press printed a series called "Victory Envelopes" for public consumption. The Sherman book lists five designs by this company. I also happened upon an image on Etsy that showed five designs with the claim that they were all part of this same series. The image from Etsy can be seen below:

I only noted two of the designs shown above as listed in the Sherman reference material. So, assuming the Etsy seller was correct that they were all printed by Advertisers Press, there could be a few more designs to add. Regardless, I do not know how many designs belonged in the Victory Envelopes series. At least five and maybe eight could be known at this time.

A "Merry Chase" Cover Too!

Last week, I featured a Merry Chase cover that started in Algeria and eventually found its way to Nice, which was then in Sardinia (not France). The basic idea is that I feel that a letter went on a Merry Chase if there are at least a few wrinkles in the route it took as it tried to find its way to the recipient. This cover has more than a few wrinkles.

First - to England

The first address for this item was to England, but that address has been crossed out and then covered up by a label that has only been partially removed. In itself, this is not a surprise since most Allied military personnel in the European theater likely had a mailing address in England from which their mail would be forwarded to their active duty location.

The full address, is not easily visible. But, after doing some research, I have determined that the address is:

Kodak House 63 Kingsway Holburn W.C. 2 England

The Kodak House was built in 1910/1911 and served as the R.A.A.F. Overseas Headquarters beginning on December 1, 1941. This is where all mail intended for active R.A.A.F. service men and women would go so it could be properly routed to that person’s location.

The Royal Australian Air Force was largely under the control of the Royal Air Force (British). So, while Flight Sergeant French was a R.A.A.F. member, he was part of an R.A.F. squadron. The bulk of Australia’s armed forces were concentrating on the Pacific, for one obvious reason - that’s where Australia is located. Most of the Australian presence in Europe was in the form of flight units.

If Sergeant French had been serving in the Pacific, this letter would likely have been directed to Australia, rather than England. But, he was not, which provides us with an opportunity for a more complex Merry Chase!

Next - to Italy

The pencil markings at the bottom of the envelope were also partially obscured by the label. But, we can see thatit reads, in part, “104 SQD.” The rest looks like “BNAP” followed by some initials.

This makes sense because Flight Sergeant French was part of the 104th RAF Squadron, which was stationed in Foggia, Italy from December 30, 1943 to October 31, 1945. So, it makes sense that the letter was forwarded on to Foggia.

I could leave it at that, but I want to point out to you that going from England to Italy was not a simple matter. There was a war on in 1944.

The territory in red would have been areas controlled by the Allies and blue would have been Axis control. Mail from England to southern Italy would have had to go the long way around to get to where it was going! I suspect the letter went from London to Lisbon, Portugal. From there it may well have gone through Africa to get to Foggia. Perhaps a specialist in this area might know more. I can only tell you that I am NOT that specialist.

The next obvious pieces of postal information that I can readily decipher are on the back of the envelope.

The first postmark reads: Field Post Office 217 - May 12, 1944. This is almost two months after the first postmark in New Castle, Indiana.

We can take a guess that this might be the Field Post Office in Foggia for the British forces. There are numerous sources that track this sort of information, but I was not able to locate one that provided me with information to confirm that this was located in Foggia.

And now back to England

It is my guess that the label shown above was affixed giving instructions that this letter should be returned to the sender at the British Field Post Office (note that this is an R.A.F. form, not R.A.A.F.). At a guess, this was sent on to the R.A.F. (British) Air Ministry Instructions in England who THEN sent it on to the Australian Airboard (administrative arm of the R.A.A.F).

Why was it forwarded? French's plane had gone down on April 17. Sadly, he was no longer available to read letters addressed to him. The report of his demise can be found later in the blog.

A long trip to Melbourne, Australia?

Now, the Australian Air Force postal service had to find a way to get the letter back to the writer.

The second postmark on the back reads: R.A.A.F. Base P.O.N. 15 July 21, 1944 M.E. - which seems to be telling me the letter did go to Australia.

Here's where I find myself out of my element. I am sure those who study military mail could decipher more of this than I can. So, if one or more such person(s) read this and can demystify some of this, I would appreciate it!

I think the purple handstamp that reads Return to Sender on Australian Airboard Instructions R Silvester Commanding Officer was applied in Australia. The Australian Airboard was the administrative arm of the Royal Australian Air Force and was located in Melbourne, Australia at the time. So I will conclude, unless proven otherwise, that this marking was applied in Melbourne.

Sadly, I cannot tell you if the letter sat in Australia for months before being forwarded on or if it got part way before it stalled at some out of the way location. There are no markings to record those travels.

In a very real way, letters of this sort, that had been sent to a service member killed in action, had to be handled like those that ended up in the Dead Letter Office in the United States. Someone had to decide if there was a way to get the letter to the recipient (or maybe a relative?) or if it could be returned to the writer.

Clearly, the pointing hands indicate that the letter was to be returned to the writer. So it was.

Back to the beginning - Indiana, USA

The final marking on the back reads: Feb 9, 1945 H.E.F.

This would be a handstamp applied by Mr. H. Edgar French. We can assume he received the letter he had written almost eleven months earlier and the "Merry Chase" ends.

Indiana to England to Italy to England to Australia to Indiana. A Merry Chase indeed.

Rebuts? What’s that about?

There is actually one more marking that is easy to miss with all of the things going on here. It runs sideways on the front of the envelope and it says:

REBUTS

This marking was typically placed on a wrapper or a band that held batches of foreign letters that could not be delivered to the addressee and were being returned. It seems that there are uncommon instances where these markings found their way onto some returned letters, like this one.

For those who might enjoy reading a bit more, this article by Tony Wawrukiewicz will shed more light.

H. Edgar French - Piano Maker

I had mentioned that H. Edgar might have written about pianos in his letter simply because it turns out that the French family were involved in that business. In fact, H. Edgar was the president of the Jesse French & Sons pianos. Recently, (in 1941) the Jesse French & Sons company was acquired by H & A Selmer.

Perhaps some of that news was forthcoming?

According to French family history, H. Edgar French had a son who was also named H. Edgar. Junior traveled to Australia at some point prior to World War II and may well have had contact with Geoffrey French at that time. That makes it possible that this letter is from Junior instead of H. Edgar Senior. Perhaps with more effort, I could determine which was the case. Either way, it seems clear that these people were related, with both families emigrating from England.

Five of Six Crew Members Lost

What must it be like to be notified that a family member is lost in war? This letter did not return to Mr. French until February of 1945, so I can guess that he had already been notified by family that Geoffrey's plane had ditched in the ocean near Corsica and that he was among the five crew members that were lost. Perhaps his family was just getting over the initial grief - and then this letter comes back in the mail to haunt them.

The RAAF Aviation History Museum provides a summary of the action that took the life of Flight Sergeant Geoffrey Charles French. The original work to compile this information by Alan Storr can be found here.

In honor of the Flight Sergeant and all others who have served and are no longer with us, I take the liberty of quoting that site for the content regarding his loss:

Service No: 422484

Born: Ryde NSW, 27 July 1917

Enlisted in the RAAF: 22 May 1942

Unit: No. 104 Squadron (RAF)

Died: Air Operations: (No. 104 Squadron Wellington aircraft LN928), off Corsica, 17 April 1944, Aged 26 Years

Buried: Unrecovered

CWGC Additional Information: Son of Albert Edgar and Elizabeth Ida French, of Hornsby, New South Wales, Australia.At 2307 hours on 16 April 1944 Wellington LN928 took off from Foggia aerodrome to attack a target at Leghorn, Italy. The following messages were received from the aircraft: 0130 hours- Landing at Borgo with engine trouble; 0206 hours – preparing to ditch, and 0209 hours – now ditching at position 42.20N 009.57E. The position was in the sea near Corsica. When the aircraft ditched, Flying Officer Gilleland was forced out of the escape hatch by the inrush of water. No other survivors were seen. He reached a dinghy and later saw a light being shone upside of the dinghy. He was rescued when a Catalina was sighted and attracted that afternoon. It was later recorded that the 5 missing members had lost their lives at sea.

The crew members of LN928 were:

Sergeant Ronald Adams (1047206) (RAFVR) (Wireless Operator Air)

Flying Officer Leslie Albert Denison (418224) (Navigator Bomb Aimer)

Sergeant William Fox (1586899) (RAFVR) (Navigator)

Flight Sergeant Geoffrey Charles French (422484) (Navigator Bomb Aimer)

Flying Officer William Campbell Gilleland (421900) (Pilot) Rescued, Discharged from the RAAF: 11 July 1945

Warrant Officer William Barry Ryan (413446) (Air Gunner)

Above is a Vickers Wellington aircraft (bomber) that would have been similar to the one Geoffrey French served on. Image taken from the wikipedia open source photos pages.

Thank you for joining me again for another Postal History Sunday. May we learn from the lessons of the past so we might avoid making the same mistakes - and people like Geoffrey Charles French could live beyond the age of 26.

Have a fine remainder of your day and an excellent week to come!

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack. And, some publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest

Thanks, Rob. You supplied some interesting and sad WW II history. I did like the colorful Victory Envelopes.