When is an article actually complete?

This is actually a question I ask myself frequently - at least once a week. Often I have to settle for “good enough” instead of offering up a version that I, personally, feel is a fully finished product. It has nothing to do with how enjoyable or interesting it is and everything to do with my knowledge and understanding changing over time. And, yes, I also expect that every piece of writing can do with yet another good edit!

Today’s offering is a good example of this concept. I first wrote about this Humbug letter in October of 2023. It was a very good article - at least I thought it was. But then I learned more and had additional thoughts about it. So, I mentioned it in a couple of other Postal History Sundays and I had a few things in some notes here and there.

Well, the article is now “complete” and I am offering it up this week! Grab a favorite beverage and snack. Put on the fuzzy slippers and settle into your favorite reading chair. And maybe we’ll all learn something new.

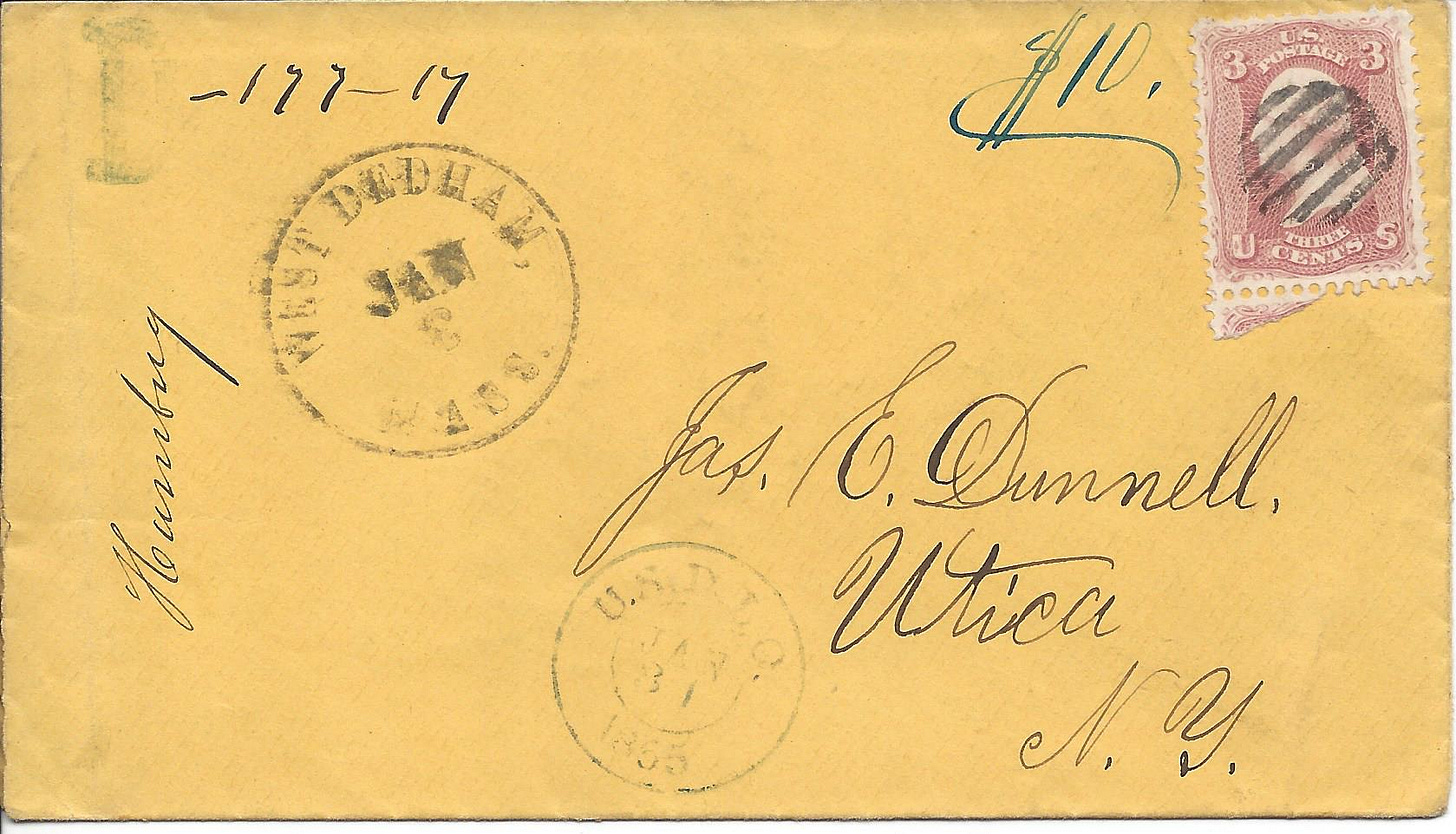

It’s just an old envelope. In fact, it is an old envelope that has already performed its duties and traveled its travels as a piece of mail. Someone has written instructions to deliver this letter to Jas (James) E Dunnell and the post offices it visited have made their marks, documenting it’s progress through the system.

It no longer holds any contents. And how could it? The back has a big slice in it that limits its ability to contain much of anything.

The job is complete, who would want it now?

Well, apparently I do.

I suppose it has the redeeming feature that it is old. A little over 160 years old, in fact. And, humans are kind of odd about the age of things. First, an item is new and we are most pleased to have it. Then, the item sees a little use and it loses its lustre and we don't want it anymore - or at least we want something newer or unused. Then, after a certain number of years - if that item has somehow survived - it becomes desirable once again.

That's how it is with many pieces of postal history. They are often seen as windows into a past that is now old enough to be the attractive sort of "old."

A torn envelope once again gets our attention. But, why this one? There must be hundreds and probably thousands of old envelopes from the 1860s that carried simple letters from one location to another in the United States for the cost of the 3 cent postage stamp found on them.

Unlike many of those old envelopes and folded letters, this cover has more clues that hint at an interesting story. And that’s why it is our featured item today.

A “Dead” Letter

This letter was initially mailed at West Dedham, Massachusetts, on January 3 and is addressed to Jas. (James) E. Dunnell in Utica, New York. The contents must not have weighed anything more than one half ounce because the three cent stamp paid for a simple letter to a destination within the United States.

However, James Dunnell never did get this letter, instead the envelope and its contents took a trip to the Dead Letter Office.

The marking towards the bottom of the envelope reads "U.S.D.L.O. Jan 31 1865." The abbreviation stands for United States Dead Letter Office, which was located in Washington, D.C. at the time.

Dead letters were mail items that were unable to be delivered to the intended recipient for any number of reasons. The US Post Office actually split Dead Letters into five categories:

Letters that remained at the post office unclaimed (typically after one month).

Letters that were deemed unmailable because the address could not be deciphered, was incomplete or the content was deemed to be "obscene."

Letters where no attempt to pay postage was made (or someone tried to re-use a postage stamp). These were classified as held for postage. And, by the time we get to 1865, they were not sent to the Dead Letter Office. Instead, they were sent to the addressee with the notation that twice the required postage be charged.

Packages over 4 pounds in weight

Letters refused at the post office by the recipient.

The Utica post office was probably large enough that they would send a small bundle of dead letters to Washington, D.C. once a month. The DLO receiving marking of January 31, 1865 seems to fit that pattern.

The Utica postmaster was supposed to classify each item being sent to the DLO under one of these categories by writing on the front of the letter. This time they wrote the word “Humbug” at the left of the envelope.

Of course, not everyone follows instructions. So, I was not too surprised that I couldn't find any of the words in the list of five categories shown above. But, still, I was expecting something that was closer to one of them: unclaimed, unmailable, held for postage, too heavy, or refused.

It is pretty obvious that this wasn't a package that weighed more than 4 pounds. And we can also remove "held for postage" from the option list.

So, this item was either unclaimed, unmailable or refused by the addressee.

Which of those words fits “Humbug?”

"Humbug" first appeared in dictionaries in 1798 and it described a deception imposed upon another person. In fact, humbug was pretty commonly used in the United States, including with respect to the secession of the states that formed the Confederate States of America.

The whole concept of a humbug becomes very clear when you view the image. The very pretty idea of secession floats over the edge of the cliff, promising one thing - while the reality of plunging to the breakers of the ocean awaits those who fall for the humbug.

On a less grand scale, humbug was often a reference to a person who represented themselves as someone they were not - often in an effort to defraud others. The image shown below depicts a person making a claim to be able to raise the devil. While they do so, to the amazement of the targeted individual, an assistant deftly removes valuables from the target's pocket.

And, of course, you might recall Scrooge in Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol (1843) and his "Bah, humbug!" It was simply his way of making a claim that the festivities and celebration of Christmas were just a big hoax.

So, apparently, the postmaster felt that James Dunnell was a humbug of some sort. But that still leaves it up to our interpretation as to how they actually classified this item. Was it unclaimed, unmailable or refused?

We can almost certainly say the letter was not refused, so it was either unclaimed (because Dunnell had skipped town?) or deemed unmailable because the postmaster was already aware that Dunnell was running some sort of scam through the mail.

The law frowned mightily on postal employees who withheld the mail from an addressee, no matter how much they might know about their humbuggery. So, it is fairly likely that this was essentially an "unclaimed" letter after it was held at the Utica post office for the required time period. But, if the Utica postmaster wanted to call attention to Dunnell, they could have bundled it up with the unmailable items and sent it on to the Dead Letter Office.

In any event, the postmaster was not allowed to open the letter - that was for those in the Dead Letter Office to do.

Fraud and the US Mail

Perhaps, it might seem that I took a bit of a jump in logic that Mr. Dunnell was a fraudster perpetuating a humbug on the public. After all, I've only given you the word "humbug" on an envelope to back it up. So, I offer this as well.

One of the duties of the Dead Letter Office was to identify valuable contents and see if they could determine who had sent them so it could be returned. It was quite common to send cash through the mail at the time and, sure enough, there is a note that, when it was opened at the DLO, it was found to contain ten dollars in cash.

In fact, this amount is also written on the back of the envelope. I am guessing that the letters that precede could be the initials of the DLO employee who processed the letter.

With the increase in use of the mail, came an increase in scams and, well, humbugs. Popular humbugs included highly touted (but unlikely) medical cures and illegal lotteries. Since lotteries were banned in most states in the 1860s, it would be normal for a person wishing to participate in one to send money via the mail. How hard would it be for a person to send out a mailing using special printed matter rates advertising a lottery at the cost of ten dollars per entry? It wouldn't take much to pocket the money and run. After all, most people lose the lottery - so who's going to follow up?

Lotteries were a good opportunity to be a long-term humbug, as we can see if we look at the Louisiana Lottery that started in 1868 and lasted until 1893. While this lottery did pay some money out, they certainly were not above bribery to get officials to look the other way if they were less than above-board. And, of course, they did what they could to stack the odds. If there were unsold tickets, they still put them into the lottery. And, if one of those were pulled as a winner, the money would go to (or stay with) the Louisiana Lottery itself.

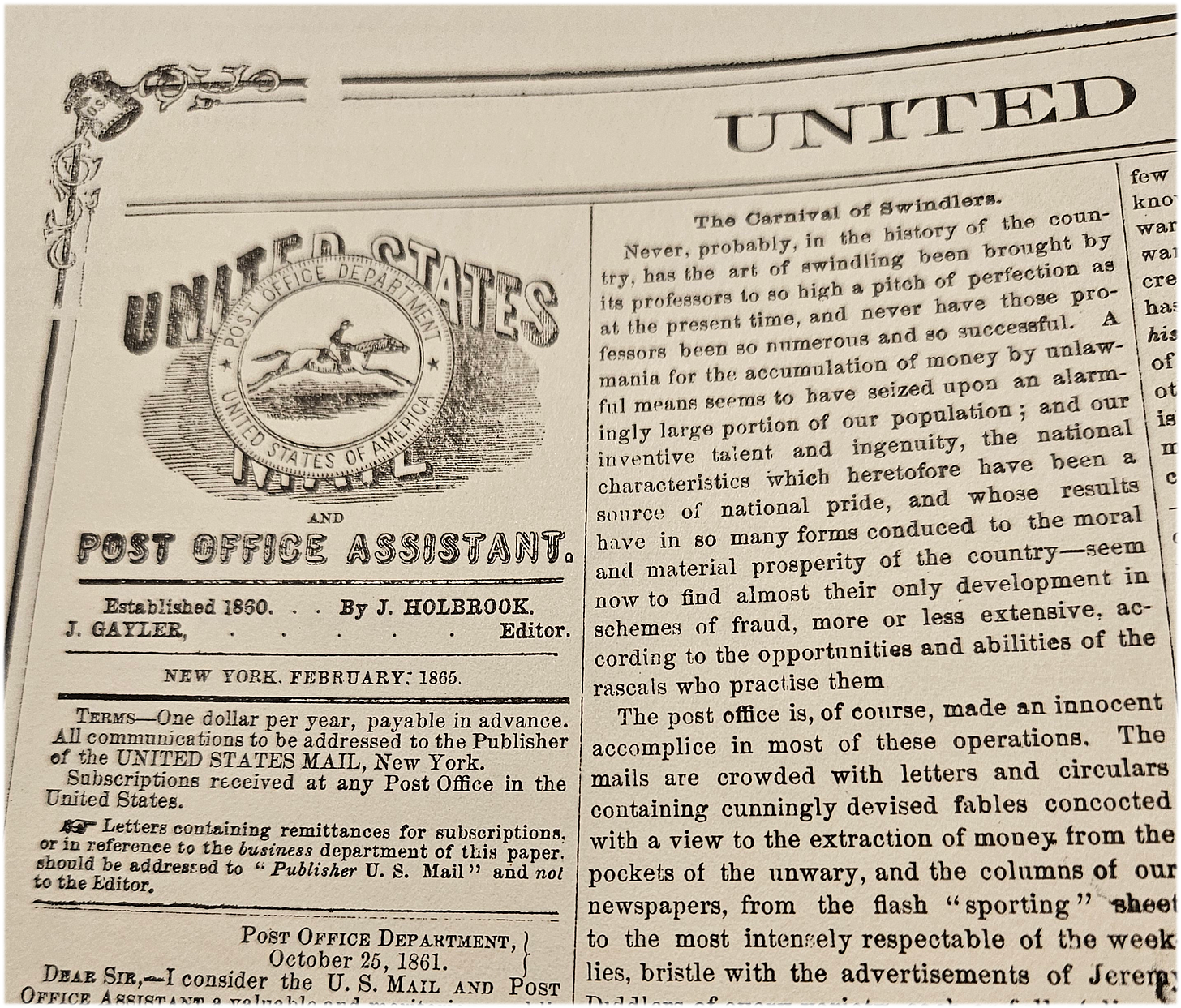

It is actually quite telling that the February 1865 issue of the US Mail and Post Office Assistant would feature an article on the very topic of swindlers using the mail. This only solidifies my case that this envelope was likely identified as one of any number of scams and was thus “unmailable.” However, there is still an outside chance that the letter was “unclaimed.” My biggest piece of evidence that this was not the case is that the letter was not held in the Utica post office for a full month.

If you're wondering why so many people were willing to be taken by scams and humbugs such as these, all you need do is read the short story by Anton Chekhov titled the Lottery Ticket. The hope and dreams that come with the possibility of winning, no matter how remote, is difficult to deny.

By the mid 1860s, mail fraud was a big enough deal that legislation was offered in 1866 and the first parts of the Mail Fraud Statute was enacted in 1868. It became illegal "to deposit in a post office to be sent by mail, any letters or circulars concerning lotteries, so-called gift concerts, or similar enterprises offering prizes of any pretext whatsoever."

But, postal employees were in 1865 had a bit of a quandary. They were very concerned about avoiding any delay of mail delivery because an 1836 law set harsh penalties for any postal service employee that hindered the progress of the mail. It was not until 1872 that the law was modified to make the mailing of matter that was intended to defraud a misdemeanor.

In other words, it seems the postmaster in Utica was VERY certain that Dunnell was up to no good.

Dead Letter Office at work

The Dead Letter Office was the last chance for an item to either find its way to the intended destination or to be returned to the writer, along with potentially valuable contents. The first step was to do what was called a "blind read" where workers would attempt to make sense of the address and addressee without opening the item. If that step failed, the item was opened in an attempt to either decipher the intended recipient or return it to the writer. This process was remarkably well done, with over 40% of the items finding their way out of the DLO to a proper home.

However, most items with no value that could not be returned or delivered were fated to be destroyed. Items with value, on the other hand were authorized to be auctioned off, according to Sec 391 of the 1866 Regulations of the Postal Department. A few interesting or unique items were maintained in a makeshift museum kept at the DLO and was of great interest to the general public.

During the Civil War, for example, numerous young men went to war and arranged to have their photographs taken with the intent of sending them to loved ones. Unfortunately, many had never sent a letter before and their effort to provide legible and clear addresses often failed. Many of these photos were posted in the post office lobby (see the video below) in an effort to help people find photos of those they knew. In fact, many of these photos were not destroyed during the normal time period out of a sense of patriotism and efforts to find relatives and loved ones to take the photos went on for some time.

To give you an idea as to the scale, the Report of the Postmaster General for 1864 indicated that 10,918 dead letters containing daguerreotypes or photographs were processed (page 17 of the report). Most of these were "sent by soldiers or their correspondents." The report for 1868 showed a dramatic increase to 125,221 dead letters with similar class items (photos), but they were clearly not for the same reasons (soldiers serving in the Civil War). It simply is an example of how the volume of the mail (and the possibility for items to need the services of the DLO) was expanding.

If you would like to read a little bit more about the Dead Letter Office, I found this blog entry on the philatelythings site to be enjoyable.

File under "D"

Perhaps you noticed the hand-stamped letter "D," followed by a series of numbers at the top left of the envelope. Well, there needed to be some sort of filing system, given the volume of mail being processed at the Dead Letter Office. The first letter of the last name of the recipient was typically used - so the "D" of "Dunnell" provided this particular letter with it's initial file letter. I have no idea how the rest of the numbering system was supposed to work. So, if someone happens to know, let me know and I'll share it later.

So, what was Dunnell up to?

I was hopeful, of course, that I might be able to dig up some sort of clues as to what James Dunnell might have been doing that would cause the Utica postmaster to declare him a "humbug." Like today, there certainly was no shortage of cons and scams that a person might perpetrate on others. Unfortunately, even after digging for a while in the Utica newspapers from that time period, I came up with nothing.

I surmised that this might have been a lottery scam. But, guess what I found soon after writing that article?

This letter - which, unfortunately, does not have a corresponding cover (envelope or wrapper). It is a lithographed circular that is promoting a lottery with an entry fee of.... ten dollars.

This letter is from the "Office of Thos Boult & Co" who professed to be General Lottery Agents. In fact, they claimed to be "Licensed" by the government. And, even better for me and my story - this letter is dated March 21st, 1865. While it is certainly not directly related to my "Humbug" envelope, it is direct evidence showing that the lottery scams were quite active at that time.

The letter opens by recognizing that most states had laws against lotteries:

"Dear Sir, From what we can learn of Public Sentiment in your State, we are satisfied that there is among your People, a strong prejudice against dealing in Lotteries and feeling that this want of Confidence, cannot be removed until some person draws a good Prize."

Of course, like any "good" scam letter, they make certain to underline the last part to get the mark's attention. The idea being proposed is that the recipient can trust them to represent them for a lottery (thus getting around the law).

"... we offer you the chance of a Handsome Prize in a Certificate of a Package of Sixteenths of Tickets on the Grand Havana Plan Lottery to be drawn ... on the 30th day of April 1865."

Thus far, the letter has not quite gone so far as to promise a positive result. However, they do go on to illustrate how much there is to gain - with so little to lose.

"... no deception lies concealed under this communication; now as our object is to increase our Business among your Citizens; by putting you in the possession of a Handsome Prize; we offer you the above described Certificate with however this understanding that after we send you the money it draws, you are to inform your friends and acquaintances that you have drawn a Prize at our Office."

Of course, the saying "thou doth protest too much" comes to mind. No, no! Of course, we don't intend to take your money and run. We just want to take your FRIENDS' money and run.

Now, they still won't promise that the mark is guaranteed a win, but...

"... if the Certificate does not draw you net at least $6000 we will send you another Certificate in one of our ever Lucky Extra Lotteries for nothing you perceive that you now have an opportunity to acquire a Handsome Prize; that may never again present itself; Improve it before it is too late, by sending your Order immediately..."

This letter seems to have everything. It tells us that we shouldn't delay and it even has it's "but wait, there's more!" moment. They'll send you another chance at a special lottery for free. It's a two for the price of one deal! And, of course, by the use of capital letters where they don't exactly belong and some judicious underlining they do a fine job of pointing us to the main issues of concern.

"To facilitate the prompt execution of our proposal use the enclosed envelope and make your remittance to our Office... Wafer or Seal your letter so that it will not come open in the Mails. Please consider this letter Strictly Private and Confidential, and send your order without delay"

So, we come to the bottom of the letter. The very same people that are hoping to improve their business by having more people participate are now attempting to tell the mark that this correspondence is a secret.

And how much was the cost to enter to have the opportunity for a "Handsome Prize?"

Ten Dollars.

So, even if the envelope to James Dunning had nothing to do with this particular scam, there was likely no end to copy cats of this scheme. It really does seem like a good possibility that the envelope held money to enter an illegal lottery.

The US Mail and Post Office Assistant was a monthly periodical that provided a wide range of material concerning the US Post Office and the mail during the 1860s. Lottery swindles show up more than once, including this one described above for a "Wright, Gordon & Co."

This is when I realized that Jas. Dunnell may not have been the individual who was running the scam. Instead, someone who would claim to be their "agent" might have attempted to pick up the mail for this, potentially fictional, individual.

Perhaps the one person from this period of history you might think of when we talk about humbugs would be P.T. Barnum. And, as a matter of fact, Barnum wrote a book titled "The Humbugs of the World" that was published in 1866. In it, he reveals a wide range of scams, including the very lottery scheme outlined by this letter.

Barnum revealed that there were several "companies" that used the same scheme including Boult & Co, T Seymour & Co, Hammett & Co, and Egerton Brothers. And, while he ridiculed the scam itself, he had very little patience for those who sent them money either.

"Now, those who buy lottery tickets are very silly and credulous, or very lazy, or both. They want to get money without earning it. This foolish and vicious wish, however, betrays them into the hands of these lottery sharks. I wish that each of these poor foolish, greedy creatures could study on this set of letters awhile. Look at them. You see that the lithographed handwriting in all four is in the same hand. You observe that each of them incloses a printed hand-bill with “scheme,” all looking as like as so many peas. They refer, you see, to the same “Havana scheme,” the same “Shelby College Lottery,” the same “managers,” and the same place of drawing. Now, see what they say. Each knave tells his fool his only object is to put said fool in possession of a handsome prize, so that fool may run round and show the money, and rope in more fools."

Later on in the same chapter, Barnum outlines another lottery scheme that appeared in late 1864. This scam took the approach of telling the mark that they had a lottery ticket with their name on it that had already won, but since they hadn't purchased the ticket, they had to do something to collect their winnings.

“Your ticket has drawn a prize of $200,”—the letters all name the same amount—“but you didn’t pay for it; and therefore are not entitled to it. Now send me $10 and I will cheat the lottery-man by altering the post-mark of your letter so that the money shall seem to have been sent before the lottery was drawn. This forgery will enable me to get the $200, which I will send you.”

Barnum outlines clearly how the post office is often used for the lottery swindle. The perpetrator could mail a batch of circulars at any post office. And since they were printed (lithographed) they qualified for the cheaper postage rates. They could drop the circulars off at a post office and leave town. There would be no office or person there to whom it could be traced.

As far as payments, those too could be directed to some smaller post office where a relatively anonymous person could call for letters. And if the postmaster or others in the town started acting as if they were suspicious, they could simply leave the area and allow the rest to go to the Dead Letter Office. All the better to run the scam again some other day without being caught.

This letter was a success for the DLO

Clearly, this particular letter was successfully returned (along with their $10) to the person who sent it. We know this because if it had not been delivered, the envelope would have been destroyed by the Dead Letter Office.

Humbug averted... until another unlikely prospect turned their eye. Or we can hope they learned their lesson. That’s something we likely will never know.

But given how much I’ve been able to uncover after finding this tired, old envelope, I’m not entirely sure that I’d bet against learning more.

Thank you for joining me. I hope you enjoyed this edition of Postal History Sunday. Have a great remainder of your day and a fine week to come.

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack.