What Are You Talking About?

Postal History Sunday #229

Here we are, looking in the rear-view mirror at 2024 and cruising forward into 2025 - whether we are ready for it or not. The good news is - I am prepared for another year of Postal History Sunday. Or, more accurately, I am as prepared as I ever am to produce more articles for your enjoyment.

For those of you who are new, this is the place where I share something I enjoy (postal history) with anyone who has any level of interest. I try to write so that people with no knowledge of the subject as well as those who have great expertise (and everyone in between) might find something of interest to make their read worthwhile. You are welcome here and I hope you might learn something new and/or be entertained by what is written.

These entries are posted at 5 AM Central US Time every Sunday. If you do not see it in your inbox, check your spam folder!

And now, pour yourself a beverage of choice. Put on those fuzzy slippers and push away your troubles for a little while. It’s time for Postal History Sunday!

A Working Definition

I would like to start the year by answering a question received from a person who is “interested, but does not (yet) collect” postal history. They were wondering if I could provide a good, working definition of “postal history.” That seemed like a fair question that was worthwhile to pursue - so let me give it a try!

Now, before you all start worrying that I’m going to go into a huge technical definition, be patient! I’ll do my best to make this as painless as possible. If you already know the definition, don’t spend time trying to poke holes in how I go about describing it, because I’m not trying to create a Webster’s dictionary entry. I’m merely trying to build a space where we all understand where we are going together.

First, I want to recognize that many people who collect postal history artifacts, like old envelopes and folded letters, often just refer to those old pieces of mail as postal history. So, I might say that I have a “postal history collection” and those who are also involved in the acquisition and study of old covers (a catch-all phrase for all sorts of items sent through the mail) would understand what I am saying.

However, postal history is more accurately defined as the study of anything having to do with the processing, transportation and delivery of mail. This can include everything from laws that dictated how mail was to be processed to historical events that influenced the carriage of mail. Postal history can include research into how postal services worked in different times and places, possibly including messenger services in ancient civilizations such as the Incas or Greeks. In other words, it is a very broad field with plenty of room to roam!

Since I like to teach and learn with examples, I thought we would take this very basic start and build on it by looking at a few postal history artifacts (covers)! I know - “postal history artifact” makes me sound like a stuffy, self-important academic. I can assure all of you that I am NOT stuffy.

So there!

The cost to mail

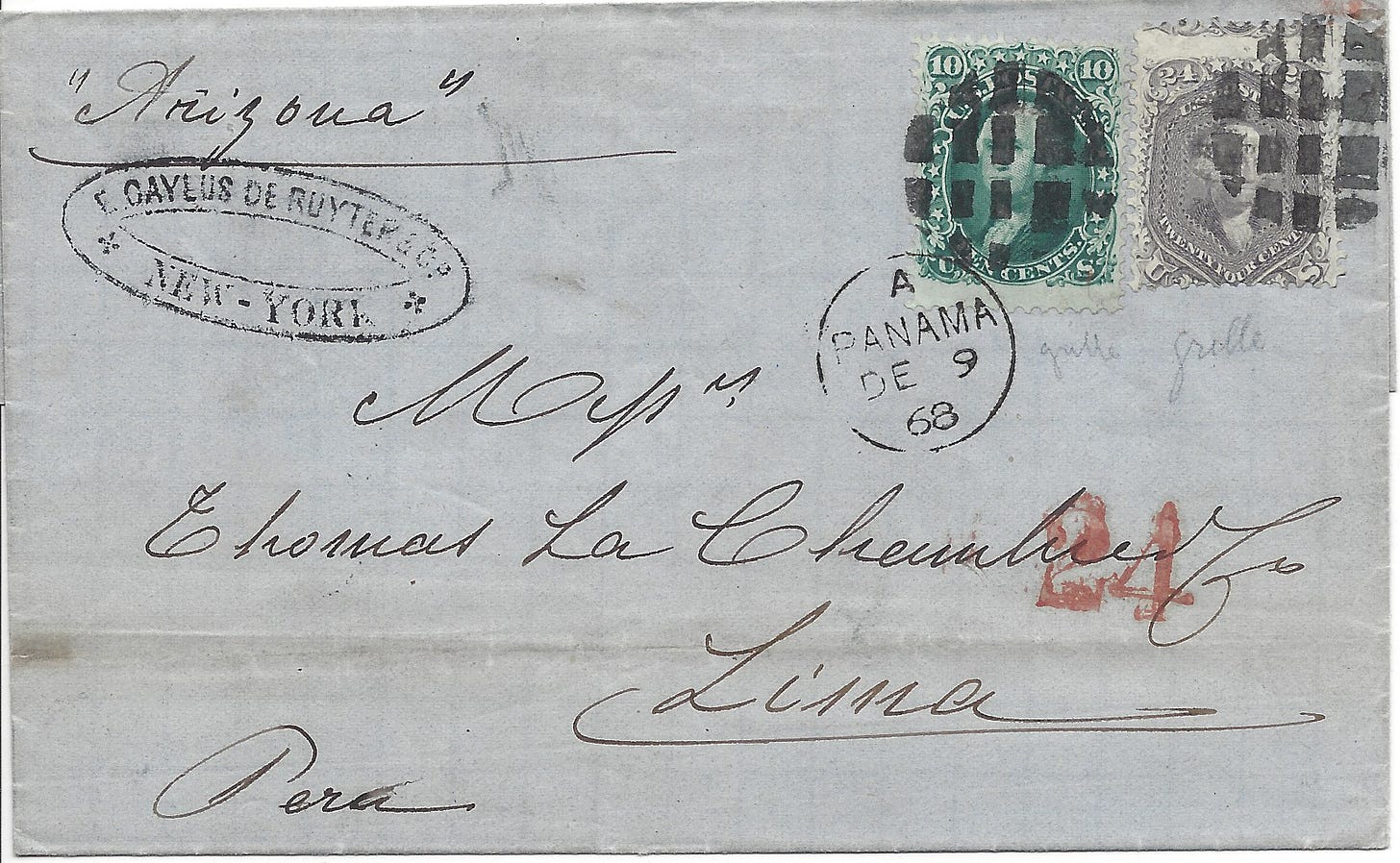

One of the most common areas for study within the realm of postal history is the postage rate(s) applied to get a piece of mail from one place to another. These costs were usually set up to be paid by the sender, by the recipient, or by a combination of the two. For example, the letter above was fully prepaid by the sender. The evidence of that prepayment comes in the form of two postage stamps located at the top right of the envelope.

Postage rates are, in my opinion, often an excellent starting point when I research a cover. They directly link a cover to a combination of the origin, the destination, a period of time and, often, a particular route that the letter took to get where it was going. This particular item was mailed in late 1868 from New York City to Lima Peru. A marking on the cover tells us it was in Panama on December 9.

There was only one advertised postage rate for mail sent from the US to Peru at the time this letter was mailed. That rate was tied to one distinct route that went through Panama. A ship under contract with the United States would (essentially) get the letter to Panama, then a British ship would travel down the West Coast of South America to take the letter to Peru. Since we have the November/December 1868 date to work with, we can see that the postage rate should have been 34 cents - or a multiple of 34 cents.

Good news! The two postage stamps have a combined value of 34 cents. So, we can conclude that this letter was a simple letter (a letter that weighed less than the base unit for a piece of letter mail).

This begs the question - how does a person find out what the postage rates were at the time a letter was mailed?

The answer to that can be quite complex. Research that involves uncovering post office and other related documents is needed to confirm the effective dates for any given rate. Happily, those who study postal history are often very willing to share what they learn. So, works like Charles Starnes’ United States Letter Rates to Foreign Destinations: 1847 to GPU-UPU provide useful tools for individuals such as myself. This doesn’t mean I can’t explore primary sources to confirm this information. But, it DOES mean that I have a fairly reliable source to reduce my research time on this particular aspect of a cover.

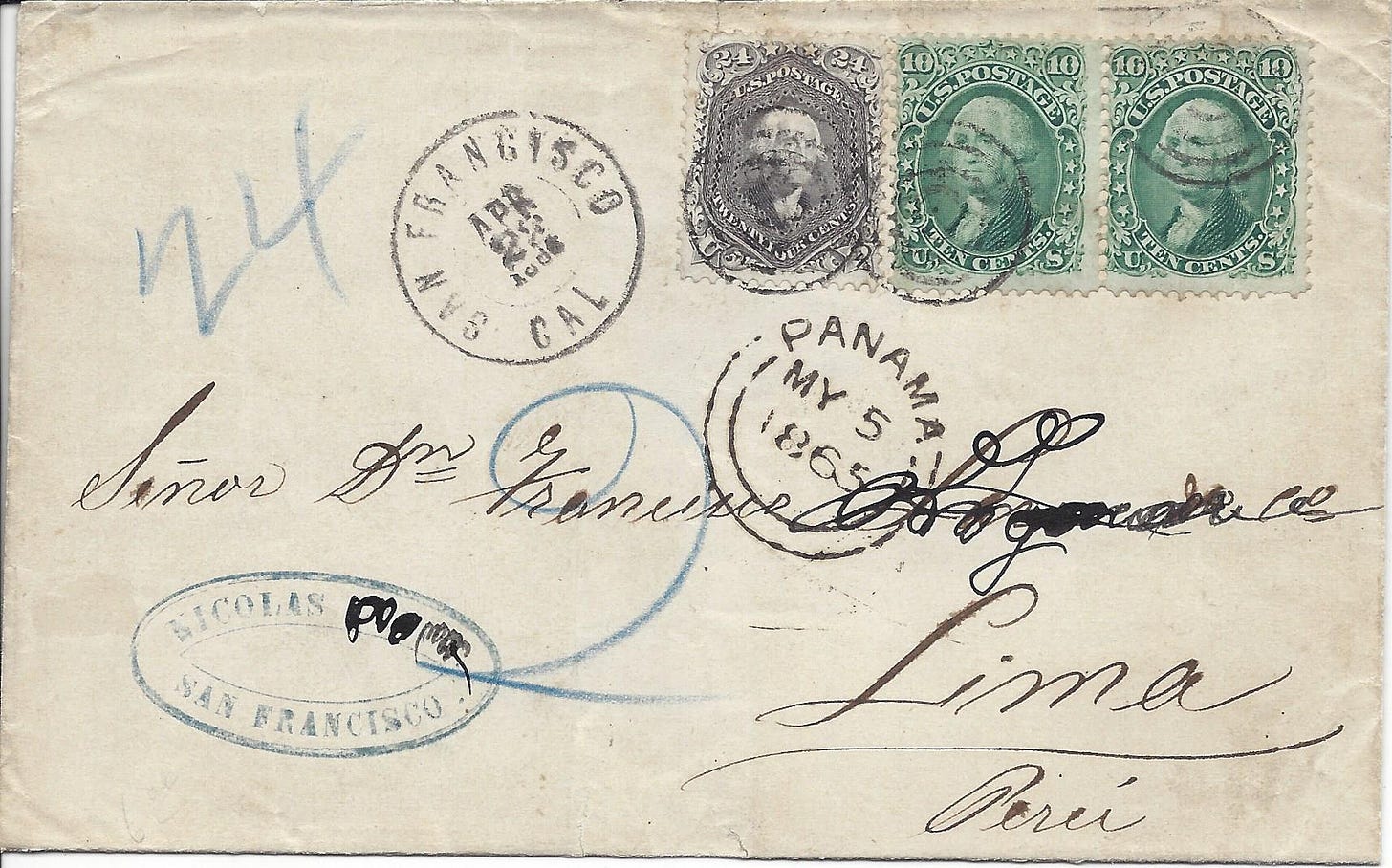

A person who is interested in focusing on the study of postage rates might seek out examples between two countries for different time periods. This allows us to illustrate how rates changed over time. Shown above is an 1865 from the US to Peru. This letter falls in the prior rate period, so the cost was 22 cents per 1/2 ounce.

This letter is not a simple letter, instead it is a double rate letter that must have weighed more than 1/2 ounce, but no more than 1 ounce. The total postage on the envelope is 44 cents and a bold “2” in blue crayon confirms that the postal clerk noted it was a heavy letter and required more postage.

This letter still traveled via Panama and it changed from a US contract ship to a British contract ship at that point.

How it got there

Another common area of study for postal history focuses on the route a letter took to get from the origin to the intended destination. Even in today’s world, there is a great deal of effort placed in determining how to efficiently move mail from, essentially, every place to every other place. Mail carrying entities have always had to seek solutions to this problem while also making adjustments for a changing world.

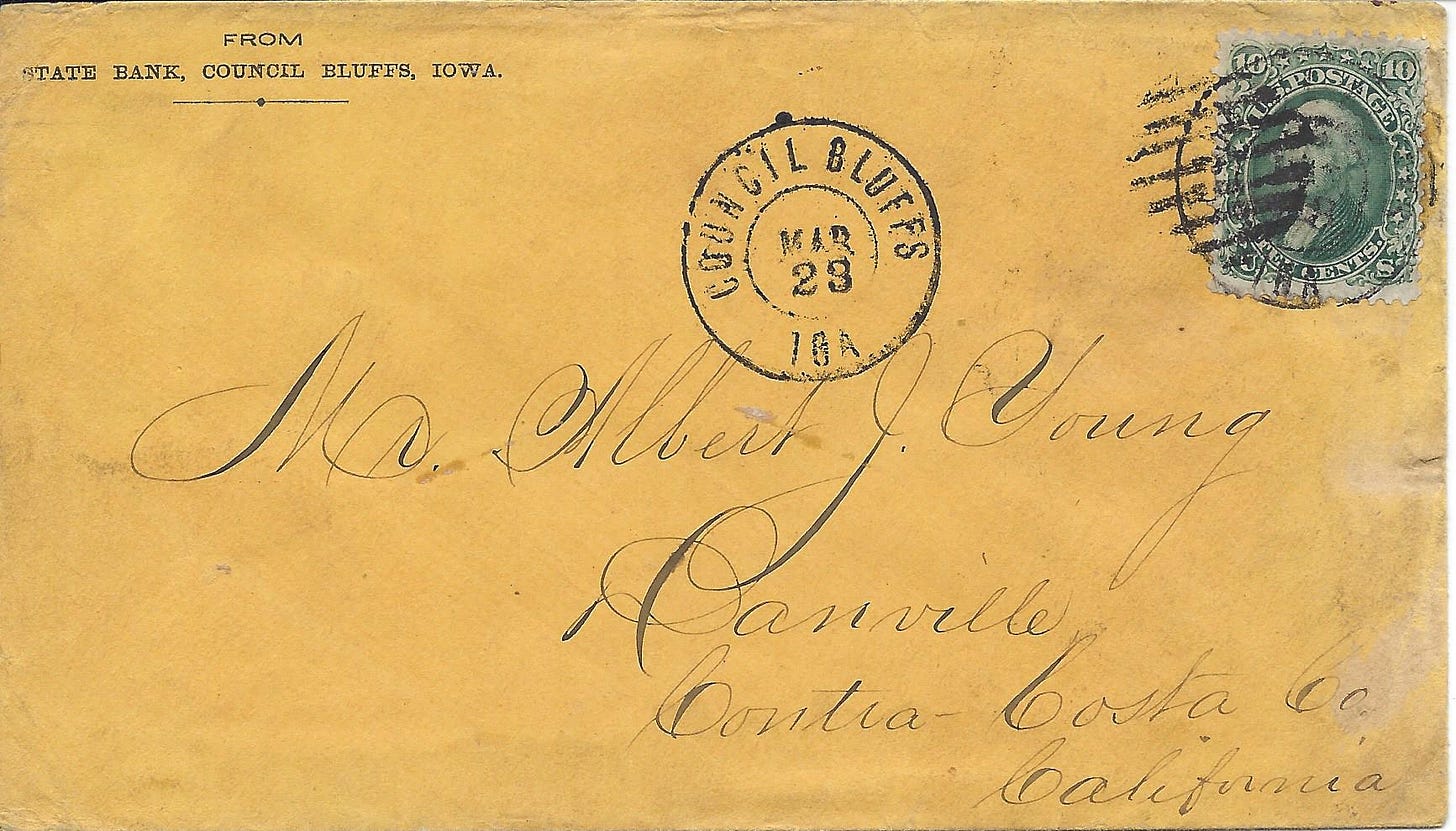

The envelope shown above was mailed in Council Bluffs, Iowa, in December of 1861 or 1862 and was addressed to Danville California. At the time, the default routing was to send the letter overland, even though construction of the trans-continental rail line was not yet begun. Council Bluffs would become the eastern terminus of this project once the Pacific Railroad Act of 1862 was signed by President Lincoln on July 1 of that year.

This letter was sent at the time when there were two postage rates in the US for internal mail. For mail that did not cross the Rockies, the rate was 3 cents per 1/2 ounce. If the letter had to cross the Rockies (even if it went around them - we’ll see more on that in a bit), the cost was 10 cents per 1/2 ounce.

This second item was mailed from San Francisco to Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and it also qualified for the 10 cent rate. However, this cover must have weighed more than 1/2 ounce and no more than 1 ounce - making the total postage cost 20 cents.

Unlike the first trans-continental letter, this one did not travel overland. Instead, it probably took a steamship from San Francisco to Panama. It then crossed the Isthmus and took another steamship to New York City. The key here is that there is a docket at lower left that reads “per Steamer,” which directed the post office to use a service other than the default, overland route.

Some of you might have noticed that I used the word “probably” when I suggested this letter went via Panama. I hedged a little because there are many examples of covers that took a route different from the one suggested by a directional docket. The docket is followed a significant amount of the time - so “probably” is correct without further corroborating evidence.

So, I looked for some support and found that a ship named Constitution left San Francisco left for Panama, carrying the mail, on October 11. Because San Francisco liked to use the date of the ship departure on their postmarks for letters to go via steamship, I can be as certain as I can possibly be that this letter was on that ship.

Markings make reading covers possible

I have heard many people describe postal history as the study of rates, routes and postal markings. It’s the postal markings that often provide us with the evidence we need to help us to figure out details for postage rates and the routes an item might have taken.

Shown above is a folded letter that was sent from Ypres, Belgium to Paris, France in 1865. We actually get the origin (Ypres) from the postal marking at the top left as well as a departure date and time March 19, 1865 at 2 PM (2S). Another postmark on the back of the letter (not shown) tells us it was on the Belgian rail line by Mouscron (in Belgium) between 7 and 8 PM. And, the red marking on the front tells us the letter crossed into France at Valenciennes. The final marking is also on the back which shows an arrival on March 20 in Paris.

Belgium and France were particularly good at providing postal markings that give a postal historian information regarding the routing of a particular letter. Not every region and certainly not every period of time provides covers with this much to work with. That’s why the study of postal regulations and procedures is also part of postal history - but we’ll talk about those things another time.

The postage rate at the time this folded letter was mailed was 40 centimes per 10 grams. Since this letter has 80 centimes in postage applied, we can deduce that the letter must have weighed more than 10 grams and no more than 20 grams. But, we can say all of this with certainty because of a postal marking. The boxed “P.D.” in black tells us that this letter was considered to be prepaid to the destination.

Traveling in style

Many people enjoy studying postal artifacts that were carried by particular modes of transportation. I could look at mail that was carried by trains, planes, ships, stagecoach, balloons and sled dogs (among other things). The development of transportation systems are often directly linked with the carriage of mail from one place to another. Early ocean-going shipping lines often relied on contracts with postal services to be financially viable. And, the development of air mail routes helped push air transport from an novelty to the mainstream.

Once again, we will find that this area of postal history has connections to rates, routes and markings.

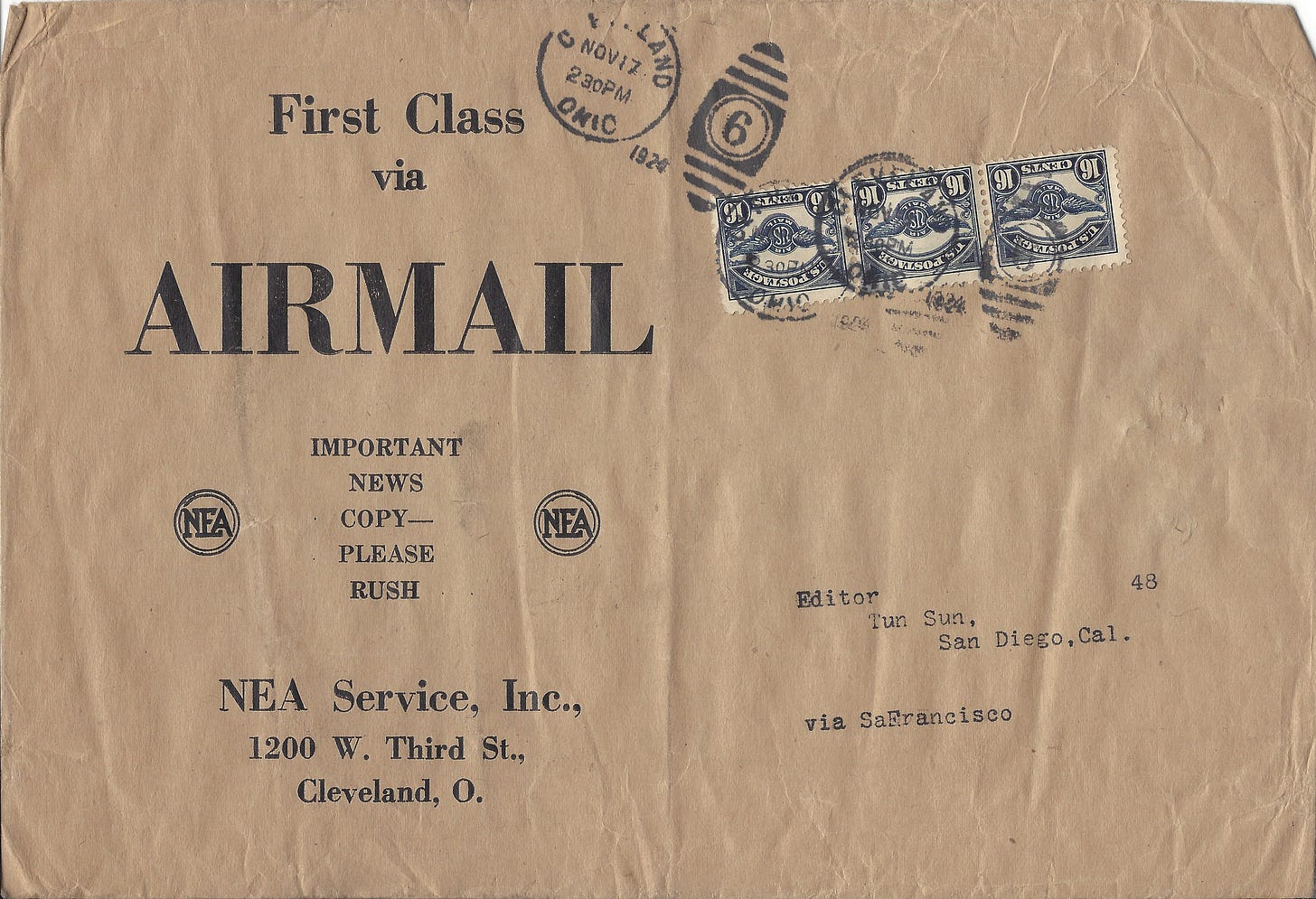

This larger envelope was mailed in Cleveland, Ohio on November 17, 1924 at 2:30 PM. Much like the first trans-continental railroad, there was one initial trans-continental air route. This route was divided into three zones (West, Central and East). Cleveland was located in the eastern zone, which means it would travel in three zones to get to San Francisco. The postage rate required to use this air mail service was 8 cents per ounce for each zone along the route (effective July 1, 1924 to Jan 31, 1927). The total postage applied here is 48 cents, so the letter must have weighed more than one ounce and no more than two ounces.

For comparison, it cost only 2 cents per ounce to send a similar letter via surface mail (mail that traveled on the surface of the earth - land or water) from anywhere in the US to anywhere in the US. So, the sender could have paid 4 cents vs the 48 cents shown here. The difference, of course, was in how quickly the mail arrived. The air mail route from New York to San Francisco averaged about 34 hours in travel time. Surface mail might take 4 1/2 days during that same time period.

The content was likely materials for a San Diego newspaper. I am sure it was important to them that they get the most recent news for their next edition.

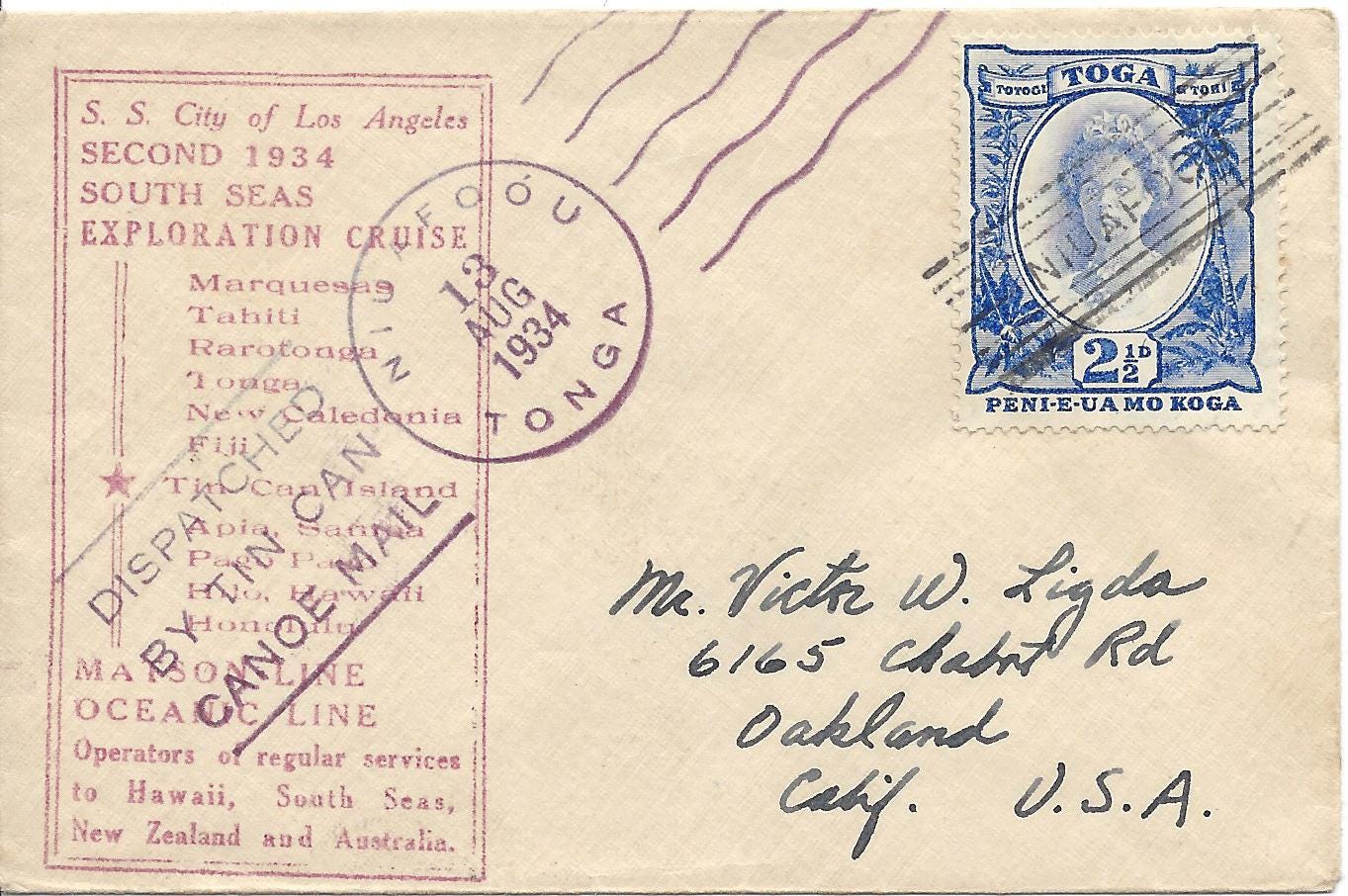

The mode of transportation can get fairly interesting, if you have a taste for things that are different. Shown above is a letter that was taken by the Tonga “Tin Can Mail” in 1934. By the time this item was mailed, the service was capitalizing on the desire of collectors to have a souvenir - so I personally feel it is marginally a piece of postal history. However, Tin Can Mail had a very real purpose (other than to create a “collectible item”) in the late 1800s.

Imagine living on an island in 1882 that has no beaches or harbours to allow ships to land - even landing a rowboat on the island was unlikely. This is exactly the situation William Travers found himself in and he very much wanted to use the services of the steamships he saw floating by (but not stopping) so he could communicate with the outside world.

Travers devised an arrangement with Tongan postal authorities where his mail was sealed in a ship's biscuit tin. The Tongan post would then arrange for the captain of one of the Union Steamship Company vessels to throw it overboard as they passed the island. Travers would then send a swimmer out to collect the tin.

If you would like to read about this topic, I found this article by Peter and Betty Billingham to be an easy read. Or, you could view this video by Graham Beck (shown below):

It wasn’t all letter mail

Thus far, we have determined that postal history includes the study of rates, routes, markings and modes of transit. And, it’s pretty obvious that we can get into a lot of trouble (or fun - if you see it my way) with just those things alone. But, you had to know there is more! Postal history includes the study of the different services rendered by postal services.

So far, I’ve only shown you items that were pieces of letter mail. But, not all correspondence was a letter (business or otherwise) from one person to another.

I realize that newspapers and magazines no longer hold the same prominence in our culture as they did even a decade or two ago. But in the 1860s and 1870s, periodicals required substantial attention from the postal services around the world to get these items from the publisher to their various destinations.

While letter mail was typically the first thing addressed in postal agreements between countries, they could not escape the fact that newspapers and other printed documents required a different type of handling. You certainly don't have to read the blurb shown below. It's just a sample of text from the 1867 convention between the United States and the United Kingdom that mentions newspapers and other "printed matter."

I offer this illustration for two reasons. First, to show that newspapers and similar printed matter were often given different postage rates than letter mail. And second, handling this kind of mailed matter was different - making them worthy of their own study.

The Belluna, Italy, newspaper (dated March 2, 1871) shown above was enclosed by a paper wrapper band that served as a surface for the mailing address and postage. The band also kept the newspaper together and prevented it from inconveniently opening up while it was in transit through the mail services. The Belluno postmark is also dated May 2nd and the newspaper arrived at the Vittorio post office the same day according the marking on the other side of the wrapper.

Post offices have offered additional services beyond the simple carriage of mail from point A to point B for quite some time. One such service has been the registration of mail which was intended to increase the tracking and security of valuable mail.

To illustrate registered mail, I offer up this larger envelope that carried some sort of letter mail content from New York City to Lahti, Finland, in July of 1935. There is 24 cents of postage on this particular item. The letter was sent as a registered letter, which carried a fee of 15 cents (effective from Dec 1, 1925 until Jan 31, 1945).

The letter weighed more than one ounce and no more than two ounces. The first ounce cost five cents in postage. Each additional ounce cost three cents more. So, the postage needed for regular letter carriage was eight cents - then we add fifteen for a registered letter totaling 23 cents. Apparently, this item was overpaid by one penny.

Sometimes it’s worth an extra penny just to get the letter on its way.

World history and social history enter the picture

If you have been reading Postal History Sunday for a while, you have probably been wondering when I would mention the interconnection of postal history with the rest of history. Events, such as wars, disease, social unrest, or the weather certainly make an impact on the transportation of mail to its destination.

Below is a folded letter on blue paper that was sent from the United States to Naples in southern Italy - and it was directly impacted by external events.

The scrawl in black ink at the top of the envelope reads "via Hamburg or Bremen." Clearly, the intention was to send this item via one of those mail services at the 22 cent rate per 1/2 ounce. But, it was off-loaded at Southampton (England) and sent via the French mails at their 21 cent per 1/4 ounce rate. In other words, this is one of those examples I was talking about where the directional docket was NOT followed. This time there was good reason.

There was this little thing that is often referred to as the Seven Weeks War (Austro-Prussian War) going on in 1866. Technically, the final battle of that war was July 24. But, at the point this letter was mailed (July 21), the postal clerk in New York knew that the route from Hamburg or Bremen to anyplace in Italy was going to be uncertain. So, they re-routed this cover via France.

And then there are postal history artifacts that come alive when we consider the social history that surrounds them. While I will concede that the social history of an item often falls outside the subject of postal history, you cannot deny how much social history can add - especially when a cover provides very little interest with respect to the postal history components.

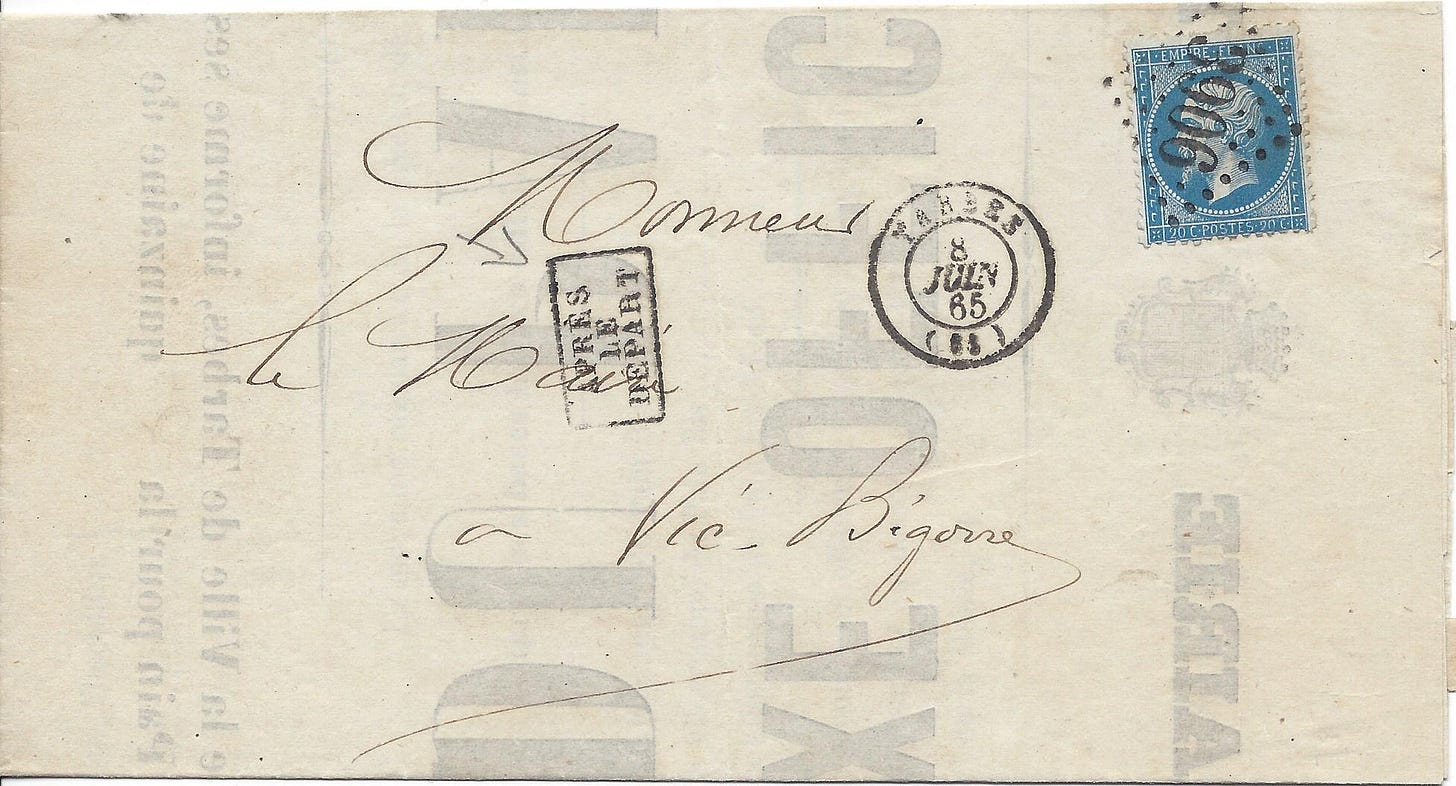

This item was mailed from Tarbes in Southern France (Hautes-Pyranees department) to nearby Vic-en-Bigorre and it is the content and purpose of the poster that makes this cover interesting.

Vic-en-Bigorre was apparently under the jurisdiction of Tarbes for the purposes of the 'taxe officieuse du pain,' which set recommended prices based on the cost of grains for bread. Bakeries posted sheets like this in their establishment so the public could see the recommended prices and compare them to the prices being requested at the bakery.

While an establishment was not required to sell their bread at these prices, you can imagine that these calculations could have influenced them. For example, if they’d been able to make their bread at a lower cost, for whatever reason, they might be tempted to raise their price to meet this suggested level. Similarly, they might unhappily cut the price lower than they would have liked, even if their costs were higher to avoid customer complaint.

The “Big Finish”

So here we are, nearing the end of this week’s Postal History Sunday and we can now say that postal history includes the study of rates, routes, markings, modes of transportation, postal regulations and procedures, and the various services provided by postal agencies. We also must recognize that certain historical events had direct impact on the carriage of mail (floods, wars, disease, etc).

I feel content to leave the definition here at this point. If someone wants to argue for the inclusion of something else or the exclusion of something I’ve provided, feel free to let me know.

But, there is certainly more that could be argued to be part of, or at least adjacent to, postal history. For example, the production of postage stamps to provide evidence of prepayment of postage is certainly connected. I mention this because our first example has something interesting going on that is certainly adjacent to the postal history aspect of the cover.

The two postage stamps on this cover have been impressed with a grill - or an embossing of a grid - that was intended to weaken the paper, increase how much ink from the cancellation postmark soaked in, and thus make it less possible for a person to illegally reuse the postage stamps. These grills were introduced into use by the US Post Office in 1868, the year this letter was mailed.

This particular cover is very interesting because it represents the earliest documented use of a 24-cent postage stamp with a grill. This postal historian thinks that’s pretty cool, even if this particular fact is more philatelic (related to the study of postage stamps) than postal history.

Thank you for joining me today! I hope you enjoyed today’s article. Have a fine remainder of your day and an excellent year to come.

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack. And, some publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest.

Excellent post - particularly enjoyed the Tonga Tin Can Mail information.

Moving information was much slower and more expensive in those days. . . and perhaps a little more carefully thought out and edited when it might take weeks or months for it to be transmitted.