It’s been one of those weeks where time made a fool of me and I find myself looking at the clock and realizing I need to get this week’s Postal History Sunday completed. This is not one of those procrastination things either. I had to help set up and prepare for an important webinar for my PAN job Thursday. Then, I was one of four speakers at the annual storytelling session at the Practical Farmers of Iowa conference on Friday. And, of course, Saturday had its things too.

Happily, both events went very well. But, rather than push out an article that would not, in my eyes, have sufficient quality to stand on its own - I decided to pull out an article from three years ago and give it a very strong edit. There is some new material, including contemporary news clippings and a significant amount of rewriting. I think you’re going to like this one as it was one of my favorites even before I gave it the most recent reworking.

So, set the troubles aside and pour yourself a favorite beverage. Put on the fuzzy slippers and settle in to your favorite reading place because….

It’s time for Postal History Sunday!

As a person who is very interesting in both learning and teaching, I am aware of the significant difference between knowing something and really knowing something. For example, I think that, after years of writing experiences, I know some things about working with words. I even think I can perform writing tasks with a fair level of success. However, if I were asked to teach a class on writing, I would be supremely uncomfortable because I am fully aware that knowing writing is not the same as really knowing writing.

This week is a postal history example of that very concept. Several years ago, I encountered a cover with a marking that was different from what I typically encountered. So, I did some research, asked some questions, and developed an acceptible understanding of the cover and the marking. As a matter of fact, other postal historians were fine with my description when I showed them this cover because nothing in what I said was incorrect.

Happily, my journey did not stop there. So, let me show how I went from knowing something to really knowing something!

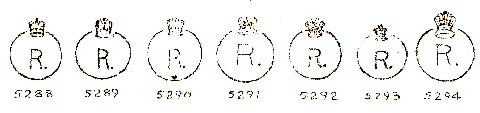

The image above is a cleaned up representation of the postal marking that encouraged my interest in everything that follows. It looks like an ornamental ring, something a person might wear, with an "R" in the center. My personal discovery of this marking came as I was seeking out examples of the mail between the United States and the United Kingdom that bore the 24-cent value from the 1861 series of postage stamps.

Before I go much further, I should explain that the 24-cent stamp was primarily used to pay the postage for mail from the US to UK. Because this is the most common use of the stamp, it is also the very best place to look for interesting variations on the main theme.

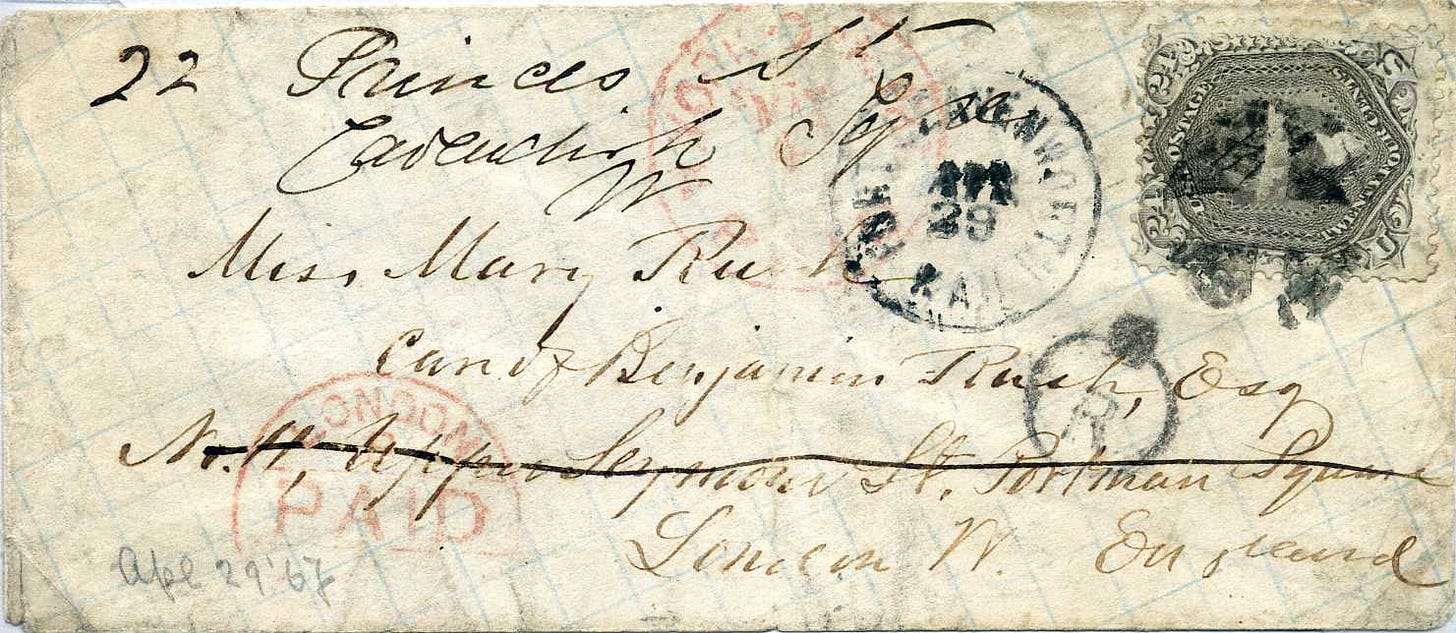

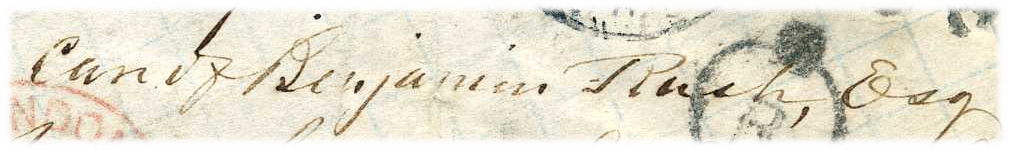

And here it is, the cover that introduced me to the postal marking in question. Let's start with the basics and go from there - just like I did back when I first acquired this cover. The initial attraction for me, once again, was the 24-cent stamp paying the postage (shown below). While the stamp isn't the prettiest copy I've ever seen, that wasn't the goal here. The goal was to learn and understand the mail between the US and the UK.

The postage rate

The active postal convention at the time was agreed on in 1848 and would continue to be in effect until the end of 1867. The postage rate was actually 48 cents per ounce of weight for a piece of letter mail. However, there was a special consideration for simple (or lighter) items. That rate was 24 cents for any letters weighing no more than 1/2 ounce. The corresponding cost for a simple letter from the United Kingdom (UK) to the United States (US) was 1 shilling.

This letter was mailed at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas on April 29 of 1867. From there, the letter likely rode on various trains to get to New York City. I would suppose, if someone wanted to do some digging, a likely railway route could be determined. I believe this one went via St Louis on it’s way to New York City.

The red marking at the top center of the envelope is a bit difficult to read, but I have had some practice and can tell you that it reads "N. York 3 Am Pkt Paid" and is bears the date May 4. This particular marking tells us several things.

The letter was considered paid by the clerk at the New York City exchange office for foreign mail.

Three cents were to be passed to the United Kingdom for their share of the postal expense.

21 cents were retained by the United States to pay for their expenses, including the cost of sending the letter across the Atlantic.

The steamship would leave New York on May 4, and it held a contract to carry mail for the United States.

Even today, as I write Postal History Sunday blog posts, I am amazed by how much we can learn from a simple marking on an envelope. When I first encountered this cover (many years ago), these were the basics that I was becoming increasingly comfortable reading as I gained experience.

How it got to London

As mentioned earlier, we could potentially construct the railway routing for this item with some level of certainty. However, there are no additional markings that provide much in the way of confirmation.

We can, on the other hand, use the postmarks on the cover to verify what happened once it got to New York City.

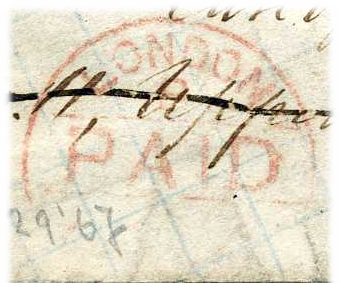

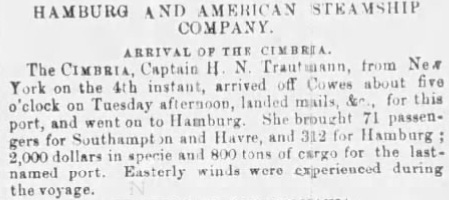

Upon arrival at New York City, the letter was processed by the exchange office and placed into a mailbag that was sealed and taken to the HAPAG line's Cimbria for carriage across the ocean. This mailbag was dropped off at Southampton on May 14 and arrived at London that day or the next, where British exchange office took it out of the mailbag and placed a red circular marking on the envelope at the bottom.

At this point, you would be correct to wonder how I came up with my arrival date because this London marking does NOT appear to have a date on it. For whatever reason, the bottom portion of the postmark, where the date would have been, was not impressed on this envelope. However, a quick look at Hubbard and Winter’s work North Atlantic Mail Sailings shows us the departure and arrival dates they discovered with their extraordinary research.

This gives me plenty of information to go looking for additional evidence of the travels of this particular ship. I find newspapers.com to be an excellent resource for papers in the United Kingdom - just in case some of you might like to use it as well. The clipping shown above tells of the arrival of the Cimbria on Tuesday, which would have been the 14th of May at about 5 PM.

Once in Southampton, this letter likely traveled to the London post office that same day, but may not have been processed until the next day.

Then it gets a bit more interesting

The first address on the envelope reads "Nr 4 Upper Seymour St. Portman Square London W." But, that address has been crossed out and a new address is written at the top right that reads "22 Princes St. Cavendish Square W." And then, there is that ring with an "R" in the middle.

So, clearly, this letter was redirected to a new address. Miss Mary Rush was no longer at the Portman Square address in London and had relocated to Cavendish Square. After a few questions and a little bit of looking, I learned that the "R" essentially indicated that the letter was "redirected" to the new address.

At this point, I felt that everything made sense and my description seemed complete. I was pleased with my own learning and happy to feel like I had done a good job of describing this particular cover. But, over time, I have learned that, while it was accurate, my understanding was not complete!

Another piece of redirected mail in the UK

As I continued exploring mail between the US and the UK, it was logical that I would see other items that were redirected to a new address. And, as I explored each one, I began to see a fundamental difference that required an explanation.

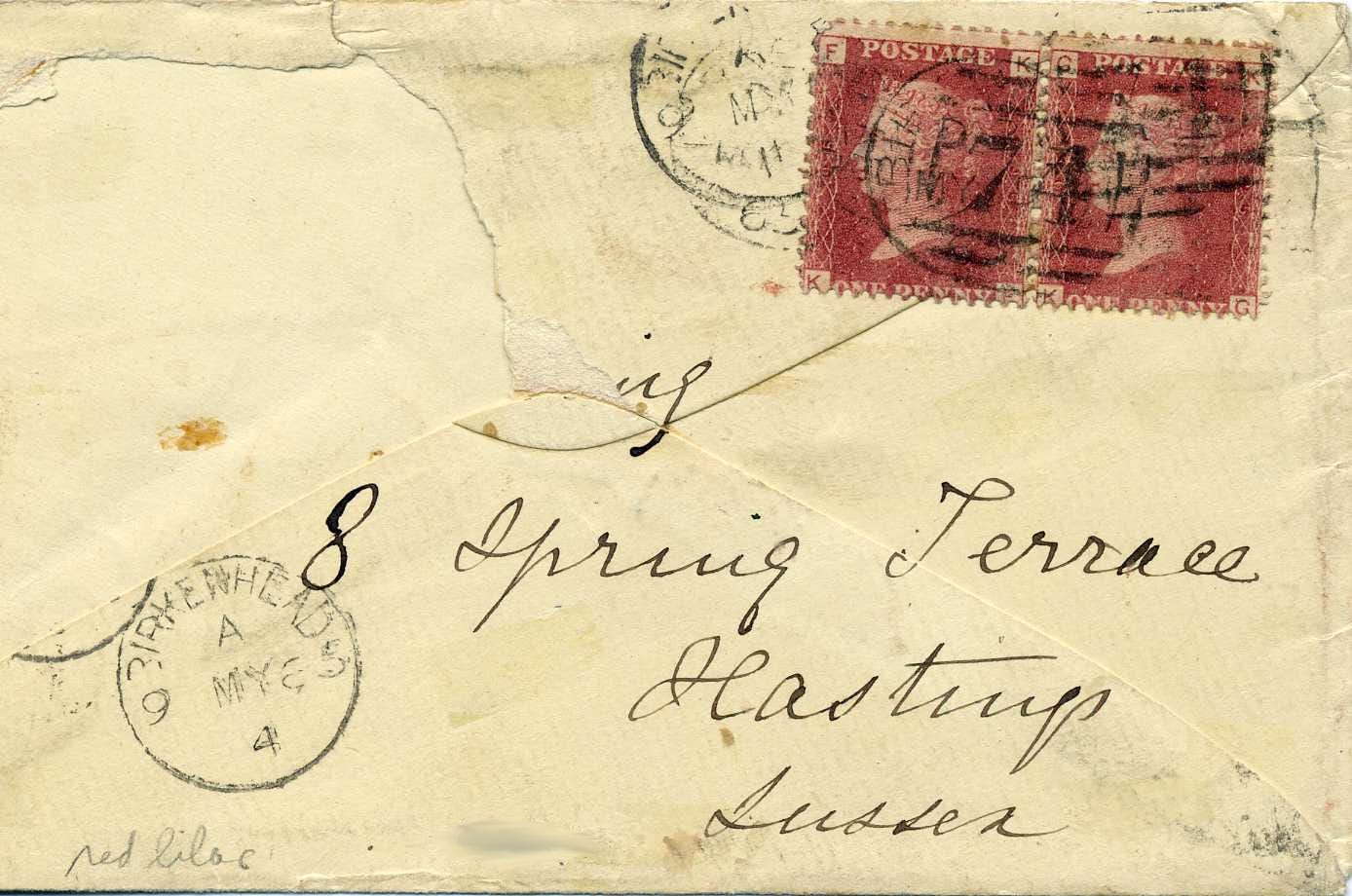

For example, here is another letter that was mailed in 1865 from Washington, D.C. to Birkenhead in the UK and then redirected.

This letter weighed more than a half ounce, but no more than one ounce - so it required 48 cents in postage. If you'll notice, there is a red "38" that tells us the British post was to receive 38 of those cents for their share of the expenses. This time around the ship had a contract with the British so THEY paid for the crossing of the Atlantic (which cost the equivalent of 32 cents US).

Once again, the original address in Birkenhead has been crossed out. And, if we look closely at the bottom left, it looks like the sender of this letter was aware that the addressee might have moved on. The docket requests that the letter be forwarded by Isaac Cooke, who knew where Mrs. W.H. Channing might be in her travels.

Mrs. W.H. Channing? Why does that sound familiar?

Oh yes! Postal History Sunday #211 - Led Astray also featured a cover to this individual! So, if you want some background regarding the recipient, I suggest you check that article.

But, there is a problem! Where was this letter supposed to be forwarded to?

Ah ha! It's on the back! And, not only is the new address in Hastings, Sussex found there, so are two one penny stamps to pay for a domestic letter that weighed over a half ounce (and no more than one ounce) in the UK.

Wait a minute! They had to PAY to have this letter forwarded or sent to the new address? I don't remember that with the first item.

Now I had a question. Why did one redirected letter require additional postage while the other did not? And why was the R in Ring postmark on one letter and not on the second one?

It's all about WHERE it was redirected TO

For a longer time than I am willing to admit, I did not explore the fine distinction between these two letters. I called the first item a "redirected" piece of mail and the second item was "remailed" or "forwarded." And all of that is technically correct. But, that did not mean I was completely aware of how the British post distinguished between the two.

Happily, I have an inquiring mind AND I wanted to know. So, I kept the questions in the back of my mind until I found time, inclination AND a lead that brought me to the answer.

So, back to the original item. There is NO evidence of additional postage paid and there are no additional postal markings other than the ring with an "R" in it. So, why would this letter have this special marking while the other one does not?

The Post Office Act of 1840 (link is to the Great Britain Philatelic Society site) set the rule that a new rate would be required for an item requiring redirection. In other words, the item had to pay additional postage in order for it to travel through the mail to the new location. This seems to match up with the 2nd item I shared - the one that shows additional postage stamps on the back.

The text from the postal act is below and was effective on Sep 1, 1840:

Article XIV. And whereas Letters and Packets sent by the Post are chargeable by Law on being re-directed and again forwarded by the Post with a new and distinct Rate of Postage: be it enacted, That on every Post Letter re-directed (whether posted with any Stamp thereon or not) there shall be charged for the Postage of such Letter, from the Place at which the same shall be re-directed to the Place of ultimate Delivery (in addition to all other Rates of Postage payable thereon), such a Rate of Postage only as the same would be liable to if prepaid.

It is not until we look at the British Postal Guide of 1856 that we find an explanation for our first cover (the one shown again above). Apparently, if the new location was WITHIN the same local delivery area, no additional postage was needed and the letter could simply be redirected to the new address. AHA!

The text from that resource is shown below for those who might like to read it.

This makes the process fairly clear. An item redirected within the jurisdiction of any "Head-Office" or one of its "Sub-Offices" would be redirected without additional charge.

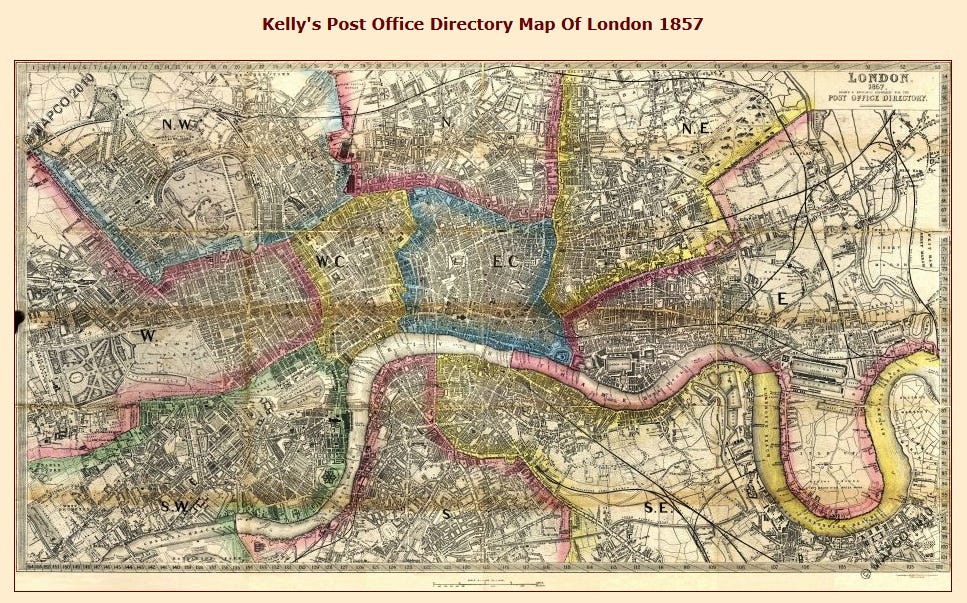

Below is a London Post Office Directory map from 1857 that may be accessed and viewed in more detail at the Mapco site. Each "Head Office" referenced in the Postal Guide translates to each of the sections shown here designated by directional markers (NW, N, EC, WC, etc).

Portman Square and Cavendish Square are both within the Western postal district and not far from each other. You can find the Western postal district outlined in pink on the left side of the map.

Additional postage was NOT required for our first item because both the old and the new address fell in the same London postal district.

Today’s second cover was directed to a different postal district, so it had to have extra postage. Everything seems to add up. So, let me throw another wrench in the works!

Here is another letter that was sent from the US to the UK. The initial address has been crossed off and a new one has been written at the top left. There is NO additional postage. Both addresses are in Holloway, a district of London and currently part of the borough of Islington (about 3 miles North of Charing Cross). This would be in the North postal district according the Kelly's map above - and the initial address does read "Holloway (N)."

But there is no "R" in ring marking - what's with that?

The R in Ring Marking

Julian Jones was kind enough to provide help, giving me a reasonable summary and this quote from a book by James Mackay (pages 281-282).

"Letters from the 1840s onwards, redirected in the same delivery area as the original address and therefore not subject to any further charge, were marked with small circular stamps surmounted by a crown and having the letter 'R' in the centre. These stamps varied considerably in diameter, the style of the letter and the shape of the crown. Ten identical stamps (5290 shown above) were issued to the London district offices on 5th April 1859."

First, you might notice that my example of the marking does not clearly show the "crown" at the top of the circle, so it makes sense that I would initially think of it as a ring. It's a first impressions thing - I have a hard time now thinking of it as anything else.

These were inspector/examiner markings used for redirecting post within a local area of London. The application of this marking indicated that the item was NOT subject to additional postage for the redirection to a new address. These R in Ring markings are known in both red and black inks.

This, of course, now begs the question as to why this last cover does not exhibit such a marking. I suppose, it is possible that the carrier learned of the new address while on the route and simply took it there without coming back to the post office. That might explain the absence of an additional marking. Or, perhaps the Holloway post office in London wasn't given a marking device. We'll just call these "things to contemplate for the future" should the opportunity to learn more present itself!

Bonus Material!

There are a few additional points of interest that come along for the ride with this Postal History Sunday!

1. The Cimbria was a new ship

The sailing from New York to Southampton on May 4th, 1867 was the return leg of the Cimbria's maiden voyage. This steamship had left Hamburg for the Hamburg-American Line (HAPAG) on April 13 and successfully delivered passengers and mail.

This was also a point of interest to me early on because this was also one of the "little differences" in a postal history item that provided me with more interest - even if it was "only a common use" from the US to the UK.

The Cimbria would serve well until 1883, when tragedy struck. The steamship collided with a British vessel by the name of the Sultan (Hull & Hamburg Line) not far from Borkum Island, after which the damaged Sultan "drifted off into the fog" despite screams and calls for help from the Cimbria.

The Cimbria sank rapidly, taking 389 lives with her and only 133 were saved on seven lifeboats that were successfully launched. More information can be found at the Wreck Site, and many newspapers of the time include an accounting of this particular event.

And, if you want even more information about the ship itself, one of the best resources is North Atlantic Seaway by N.R.P.Bonsor, for specific information on Cimbria go to vol.1,p.389

2. Not THAT Benjamin Rush, but related

If you are familiar with Revolutionary War period history, you might perk up at the name Benjamin Rush, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence. Well, this is his grandson, who was a writer and a lawyer.

Of particular interest is this item, that is titled "William B. Reed, of Chestnut Hill, Philadelphia. Expert in the art of exhumation of the dead." Yes - that is quite the title - is it not?

A very cool coincidence is that this article was being sent to the United States on a steamship DEPARTING the UK on May 4th, 1867.... the same date the Cimbria set off from New York, carrying our featured letter to Mary Rush. These two things must have passed each other on the Atlantic Ocean.

In about fifteen pages of text, Rush takes on William B Reed, who apparently had taken it upon himself to sully the name of Rush's grandfather and namesake. A small segment of Rush's writing is below, from the site listed above.

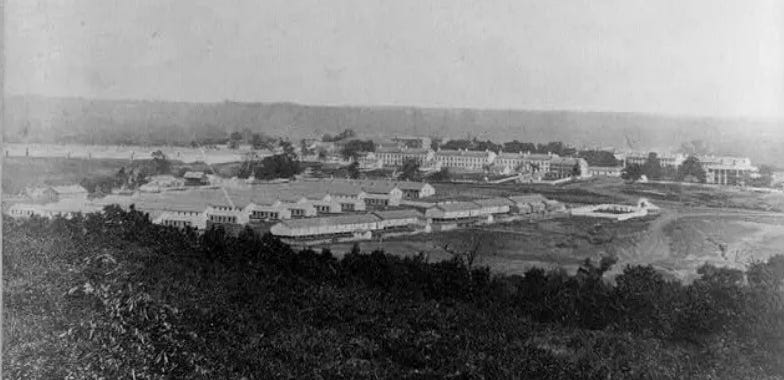

3. Fort Leavenworth, Kansas

You might recognize the name of Leavenworth for the federal prison that was built in the 20th century. but, in the early 1860s, Fort Leavenworth was actually a key training point for Union soldiers in an effort to hold an area that actually had strong feelings for the Confederacy - a moment in history known as Bleeding Kansas or the Border War.

By 1867, the focus of the military at Fort Leavenworth had more to do with conflict between the US and the Native American populations.

This 1867 photo by Alexander Gardner can be found at this location (viewed Jan 7, 2022) and one brief history can be found at the site that hosts the photo found above. A contemporary event at Leavenworth would be the court martial of General Custer in August of 1867.

And, if you want even more Leavenworth history, let me suggest A Brief History of Fort Leavenworth: 1827-1983, edited by Dr. John W. Partin.

For good measure, here is another contemporary photo from the Library of Congress. Why not? Let's do this thing right.

Thank you again for joining me for Postal History Sunday! I hope you enjoyed today’s entry.

Have a great remainder of your day and a fine week to come.

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack. And, some publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest.