Exceptions to the Rule

Postal History Sunday #217

This week we’re going to go with the short introduction. Grab yourself a beverage of choice and a snack to go with it. Push your troubles to the side - just like a cat nudging any object worth its attention to the edge of the table. Maybe those problems will no longer look quite so daunting after they’ve shattered on the floor. Put on the fuzzy slippers and find yourself a comfortable place to read for a few minutes.

It’s time for Postal History Sunday!

The Rule: 1 shilling for a simple letter from the UK to the US

The United States and United Kingdom concluded negotiations for a postal agreement at the end of 1848 and both put the articles of that convention into effect early in 1849. This treaty established exchange offices, made allowances for mail traveling through either the US or UK to another nation and set postage rates. This postal convention remained in effect until the end of 1867 - almost 20 years - which is longer than many postal treaties of the time.

From the perspective of the United States, the cost of mailing a simple letter was 24 cents. A simple letter was the most common piece of letter mail. To qualify, the item could weigh no more than 1/2 ounce.

That 24 cent in postage cost was split into three parts:

5 cents for the US surface mail,

16 cents for the trans-Atlantic crossing, and

3 cents for the British surface mail.

The equivalent costs from the perspective of the United Kingdom was 1 shilling for a simple letter (1 shilling = 12 pence).

To make it easy to reference, I find it helpful to see those amounts side by side:

Simple letter cost: 24 cents = 1 shilling (12 pence)

US surface mail: 5 cents = 2.5 pence (or 2.5 d)

trans-Atlantic crossing: 16 cents = 8 d

British surface mail: 3 cents = 1.5 d

The highest volume of letter mail, by far, were the simple letters that traveled between nations. So, of course, postal history collectors are most likely to find examples simple letters. When it comes to mail from the UK to the US in the 1850s and 60s, the most common items will illustrate either a fully paid or unpaid simple letter costing 1 shilling in postage.

When I am attempting to learn about a new area of postal history, I typically focus first on learning the characteristics of the simple letters. Mail between the US and UK during this period is actually something I have studied for quite some time, so it makes sense to use it as an example to illustrate my point. Once I became comfortable with the most common items, I was able to treat the pattern they show as the “rule” that most items I encounter will follow. And, once I understand “the rule” I can more easily identify the exceptions.

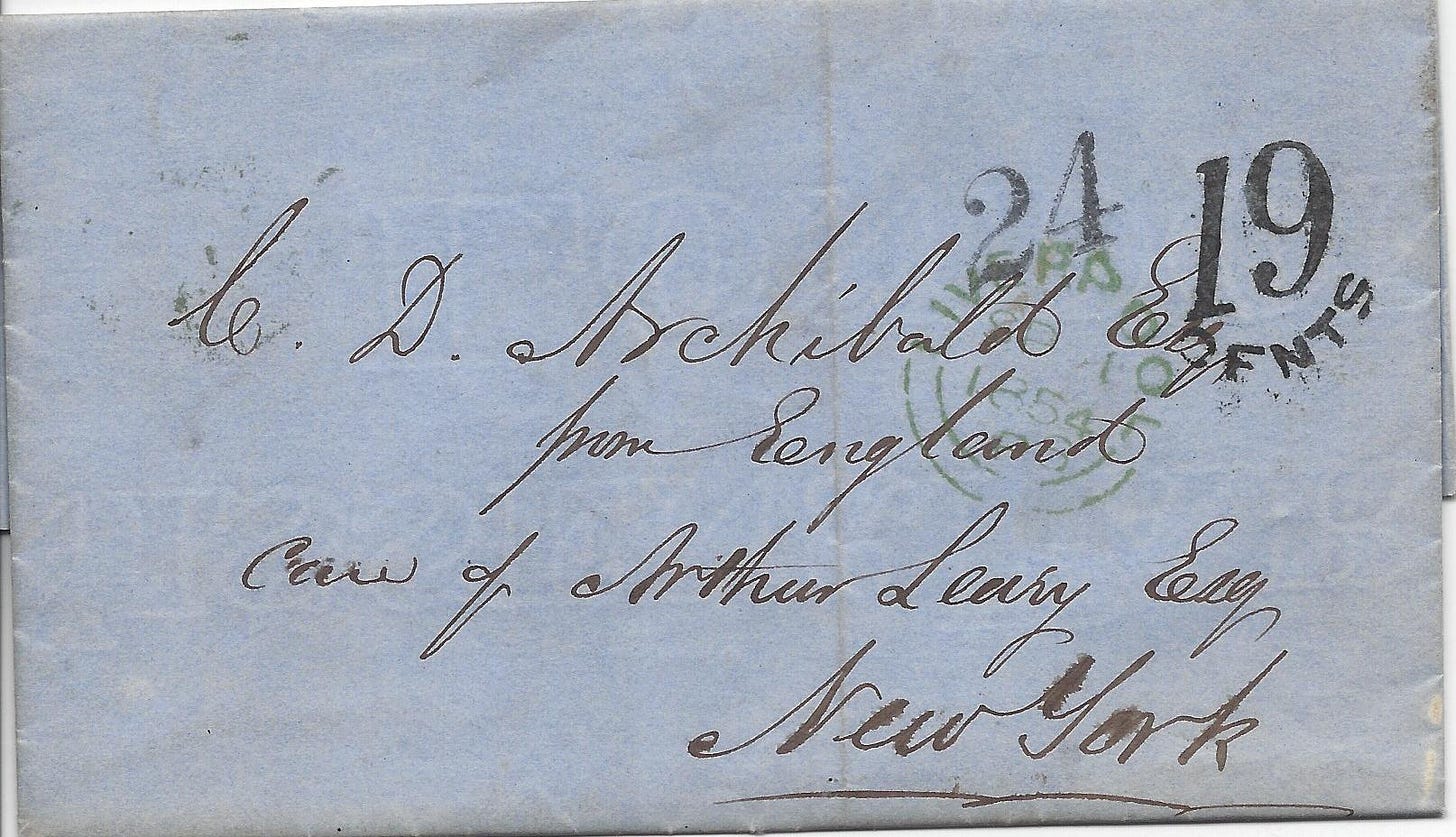

Shown above is an 1854 simple letter mailed at Liverpool on September 10 to New York City. The treaty allowed for items to be sent paid or unpaid, but partial payment ended up being treated as wholly unpaid.* This letter was sent unpaid, leaving the recipient to pay 24 cents in postage for the privilege of accepting this letter.

If you look, you will see a “24” in black ink - indicating the amount of postage due. The postal agreement set a standard that accepted red ink as an indication that the postage was fully paid in the originating country and black ink sent the message that postage was due. Also, the sending exchange office was to include the word “paid” to confirm payment for the receiving exchange office.

The part that often confounds people who are new to this particular agreement is the “19 cents” marking that is included on the cover. Why would the postal authorities put two different due amounts on one letter?

The answer is that the “24” is the due amount. The “19 cents” marking is intended to keep track of the accounting between the US and the UK. In this case, the United Kingdom is telling the US that it expects 19 cents of the 24 cents to come to them.

Why?

Well, they wanted 3 cents for their surface mail portion AND since the ship that carried this letter was under contract with the British, they also wanted the 16 cents for that portion of the expenses. In other words, the US was going to collect postage and the accounting mark indicated how much when to the British.

*There was an exception to the wholly paid/unpaid rule that had to do with something called “open mail” that we will talk about in another Postal History Sunday.

Even items following the rule can have a social history sidebar

Our first letter was sent to C. D. Archibald “from England” care of Arthur Leary in New York. As is frequently the case for early letter mail, the recipient and the person it was sent “care of” were affluant. Those with money, power, or a business were more likely to send and receive mail in the early to mid-1800s than much of the population. But, perhaps more important for those of us who collect old pieces of postal history, they were more likely to keep these items for their own records rather than discard them (or reuse the paper for other purposes).

Charles Dickson Archibald (1802-1868) was born in Truro, Nova Scotia and graduated from Pictou Academy. He had a relatively brief political career as a young man in Nova Scotia, but upon his marriage to Bridget Walker (an heiress to an estate in Lancashire), he moved to England. Archibald continued to maintain both business and family connections in the Canadian provinces, frequently traveling back to North America from his home in England.

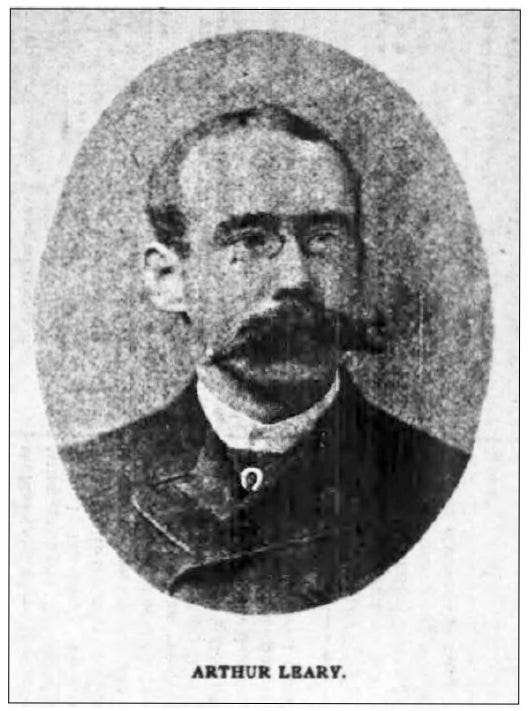

Arthur Leary, on the other hand, was an influential businessman in New York City during the mid-1800s. He was a director of a wide range of concerns, including the Illinois Central Railroad and the Pacific Mail Steamship Company. Leary was on McCallister’s “List of 400” of New York City’s society leaders that was published on page 5 of the February 16, 1892 New York Times.

We could take a guess that Leary, like other prominent figures, might attract foreign dignitaries to their residences. It does not seem out of the ordinary that someone like Archibald might impose upon Leary - especially if there were overlapping business interests.

The Heavy Letter Exception

One exception to the “rule” is fairly easy to understand. If the letter weighed more than 1/2 ounce, it was no longer a simple letter and it would require more postage to get it from the UK to the US.

The cover shown above left Liverpool, England, in August of 1867 and was sent to Houston, Texas, in the US. Apparently, it weighed more than one ounce, but not more than 1.5 ounces. Since the postage rate beginning in April of 1866 was 1 shilling per 1/2 ounce, this letter needed 3 shillings in postage.

This letter has two postage stamps, one representing 1 shilling in postage and the other 2 shillings, for a total of three shillings paid. The red, circular New York marking at the left shows that the letter was recognized as fully paid. The red pencil "15" indicates that the British Post was aware that fifteen US cents (5 cents x 3) needed to be sent to cover the US portion of the expenses.

If you would like to learn more about the oddities of triple rate covers, this Postal History Sunday might be interesting to you.

The recipient of this letter was most likely Thomas William House (1814-1880) who emigrated to New York City in 1835 and started his career as a Houson businessman in 1838. He served as mayor in 1862 and was running T.W. House & Company, Texas’ largest retailer, at the time this letter was received. At the time of House’s death in 1880, he was recognize as one of the wealthiest individuals in the state.

The “Before we agree, let’s disagree” exception

The cover above certainly looks like it might follow the rule because it has a single 1 shilling stamp that was acknowledged at Liverpool, where this letter was mailed. I will admit that this is a bit of a red herring because it is really an exception BECAUSE it was sent just before the treaty went into effect. Prior to the treaty, 1 shilling would have paid the cost of the letter to get to the US port of entry. The recipient would then be required to pay the surface mail cost (5 or 10 cents).

However, I wanted to highlight the disagreement that would be resolved when the convention officially went into effect. This letter shows us an example where the United States ignored the 1 shilling (24 cents) prepayment and asked the Smith, Dove & Company to pay 29 cents for this letter.

So, what happened?

In the 1840s, the Cunard Steamship Line, a British company, was the most reliable packet line to carry mail across the Atlantic Ocean. So, of course, the part of the postage that paid for the steamship, more often than not, was going to go to Cunard. However, there was a steamship company (the Ocean Line) that was under contract to carry mail for the United States from New York City to Bremen - with a stop at Southampton, England.

The British didn’t like the idea of the trans-Atlantic portion of the postage going to a steamship line that wasn’t one of theirs. So, they treated all mail carried by the Ocean Line as if it was not prepaid in the United States. The recipient of such mail had to pay the full 1 shilling as if it no postage had been paid at all. This is typically referred to as the exclusionary rate implemented by the British to try to enforce the use of British contract ships for the Atlantic crossing.

The letter shown above is a retaliatory rate cover. The US, not appreciating the exclusionary rate, decided to do something similar for letters carried by the Cunard Line to the United States. The prepaid postage was ignored. The 24-cent packet rate was owed PLUS the surface mail rate, which would be an additional 5 or 10 cents depending on the distance it had to travel.

The “California is a long way” exception

In Postal History Sunday #213, we looked at covers that traveled between the United Kingdom and the West Coast. Until July of 1863, the internal letter rate for letters that crossed the Rocky Mountains was different than the regular postage rate, which was 3 cents per 1/2 ounce. Instead, the cost was 10 cents per 1/2 ounce. As a result, a person in San Francisco (for example) was required to pay 29 cents, instead of 24 cents, to mail a letter to England. Similarly, a person in the UK would have to pay 14 1/2 pence to send a letter to San Francisco.

It is not terribly hard to figure out where the 29 cent amount comes from here. Remember the breakdown of the 24 cent postage rate? Five cents was to be retained by the United States for their surface mail. However, the internal mail cost for a letter on the east coast to get to San Francisco was ten cents. Hence, an additional five cents (2.5 d) was added for letters between the UK and the West Coast.

The 1860 simple letter shown above has three British stamps total 1 shilling and 3 pence in postage, which is a 1/2 penny overpay. The British post had no 1/2 penny postage stamp, so this rate was a bit of an inconvenience. Either a person overpaid a little or they paid the difference in cash.

The “You should manage your time better” exception

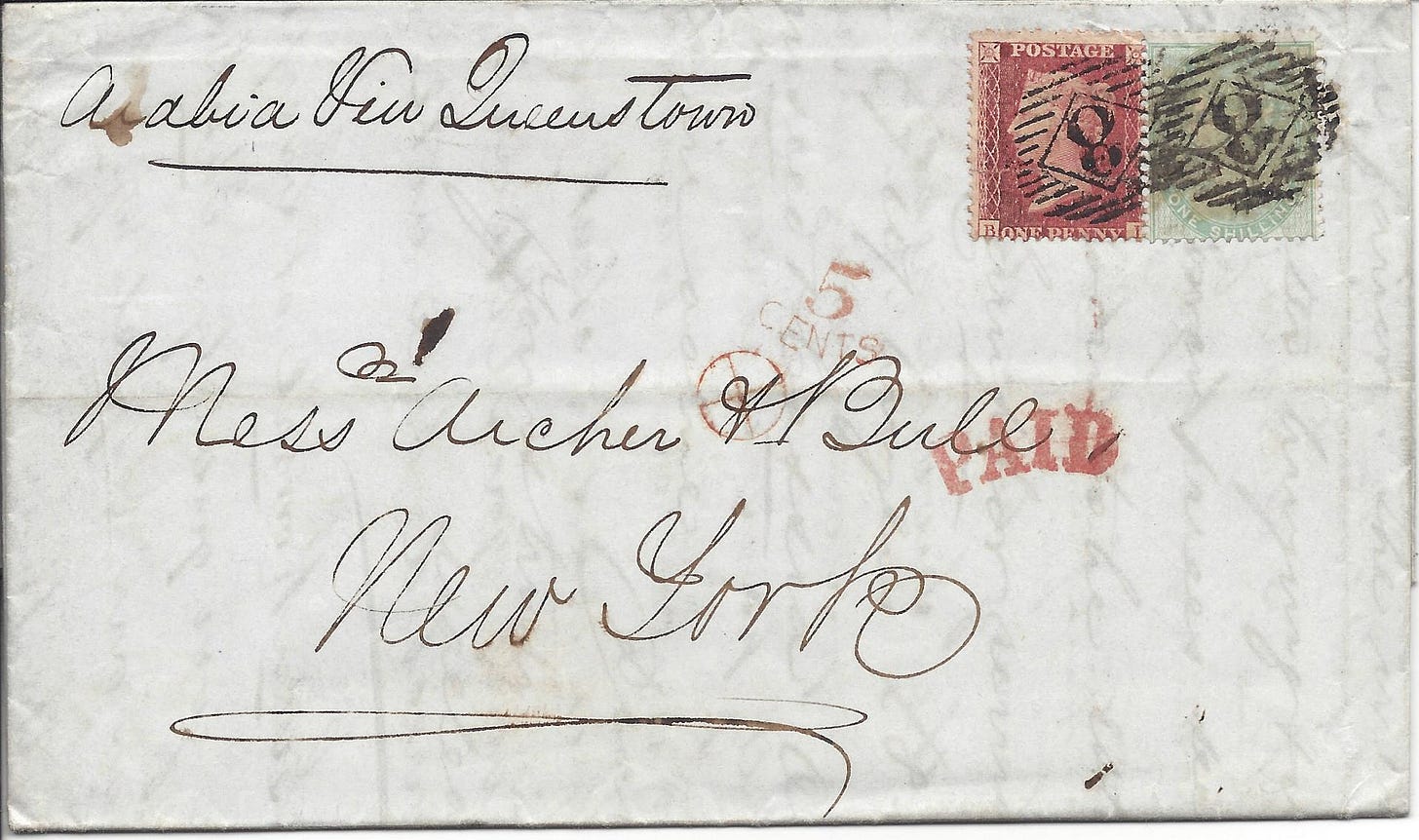

British post offices had closing times that reflected the departure of the mail train, ship or coach that was to carry the mail. When it came to foreign mail at the London offices, there would be multiple closing times depending on the destination. The letter shown above was destined for a ship departing Queenstown - in Ireland - for New York City.

The British Post, realizing that there were always going to be people pleading for an exception or favor to get a letter into the mailstream before it left, created options to pay a late fee so the letter could be processed after the mail closing time. Of course, once the mailbag left, there wasn’t anything anyone could do.

The letter shown above includes a 1 shilling stamp that paid the postage for a simple letter from the UK to the US. However, there is an extra 1 penny stamp that gives us evidence that the sender of this letter took advantage of late mail service.

The mailbag for letters to the US was not yet sealed and the train to Holyhead (on the way to Queenstown) had not left. For an extra penny, the clerks processed the letter and put it into the mailbag.

The customer was probably relieved that the letter was on its way - though I suspect they still grumbled about paying that extra penny. On the other hand, I am a happy postal historian who can illustrate this exception to the rule - so I am glad they paid the extra penny.

The “You must feel a great need for this letter to get to its destination” exception

This next example probably deserves it’s own Postal History Sunday article at some point in time. But, for now, we’ll go with the simple explanation in the interest of time (both mine and yours).

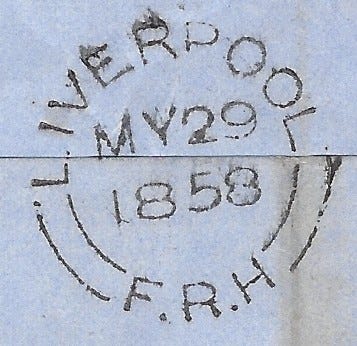

This letter has two 1-shilling stamps, which would tempt us into thinking that it is a heavy (double weight) letter requiring 2 shillings in postage. However, the big, red “5” indicates that we would be wrong with this assumption. If this were a double weight letter, the amount of postage to be sent to the US should be twice that amount (10 cents). So, there must be another reason for that extra shilling in postage.

Well, there is, and the reason is related to the 1 penny late fee that the prior cover illustrated. But, to understand, let’s look at the back of this cover.

The key is the letters “F.R.H.” These indicate that the letter was brought to the Floating Receiving House at the Liverpool docks where the Cunard steamers were to leave carrying the mail for the United States.

The letter itself must have been written at the dock since the letter writer starts with “We have just time before the last bag closes this morning...”

For those who felt the great need to get a letter out just before the steamship departed Liverpool, on its way to Queenstown and then New York City, they could pay an additional shilling in postage. This very short letter seems to simply be a report on the progress of another ship - very likely one that was carrying a shipment from the letter writer to the recipient.

I hope that report was worth the extra shilling.

The “How many exceptions would you like?” exception

Our last example for today was the subject of its own Postal History Sunday. If you want to read the details - which are quite interesting - take that link. Otherwise, I will leave you with the brief description:

This envelope was mailed at the Lombard Street post office in London on, or just before, October 1, 1864. The letter was sent as a registered letter. The total postage required to mail it was 1 shilling and 6 pence, with the 6 pence being the registration fee. It arrived in New York on October 15. The addressee could not be found at the address given. So, the post office advertised the letter in the newspaper three times. At that point, this cover was identified as a dead letter and was eventually returned to the United Kingdom.

I’m sure it would have been nice if this cover only showed the proper payment of the registration fee and successful delivery. But, I won’t say “no” to this much more complex - and interesting - story.

Thank you for joining me today. Have a fine remainder of your day and an excellent week to come.

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack. And, some publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest.