The weeks roll by and Sunday comes up at the front (or back if you prefer to think that way) of each one on a regular basis. And somehow, some way, Postal History Sunday keeps up with the turning of the calendar for one more week.

So, let’s set those troubles on the edge of the table and see if the cat will knock them off for us. Or maybe the dog will think they would make an excellent chew toy. Then, go get yourself a beverage of your choice and maybe even treat yourself with a snack. Put on those fuzzy slippers, settle in, and enjoy this week’s edition of Postal History Sunday!

Dead Letter in London

I think most everyone who might be reading this has some idea of how sending a letter works, even if they have not sent one for quite some time (though there might be some here who have never sent a letter via the mail). In the 1800s, the concept was similar to what we know, but with a few notable differences.

A person would write place their letter into some sort of a wrapper. This wrapper could be another sheet of paper which could be folded over on itself to create an enclosure. Or, as time progressed through the 1800s, envelopes began to replace folded lettersheets as the preferred method for sending mail.

Once the content was securely wrapped up in the cover sheet or envelope (postal historians call both of these covers), the name of the recipient and an appropriate address was written to give the postal services a destination for the letter. The post office could then use the outside of the cover to place markings that helped to track the progress of the letter and tell postal clerks further down the line whether a letter was fully paid, or if more postage was due from the recipient.

And that is probably one of the biggest differences between the present day and much of the 1800s. A person had the option of sending a letter unpaid, expecting the recipient to foot the bill. It wasn’t until postal reforms in the mid 1800s, which included the invention of the postage stamp, that prepayment became more common - and then required - to mail a letter.

But what happened if a letter is properly sealed up and correctly prepaid, but the post was unable to deliver that letter? There are numerous possible reasons why a letter could not be delivered. Perhaps the address is unreadable or the person moved on and no one there knows where they went. If the letter could not be delivered, what should the postal service do?

And that brings us to today’s topic - dead letters. These are letters that could not, for whatever reason, be delivered to the intended recipient.

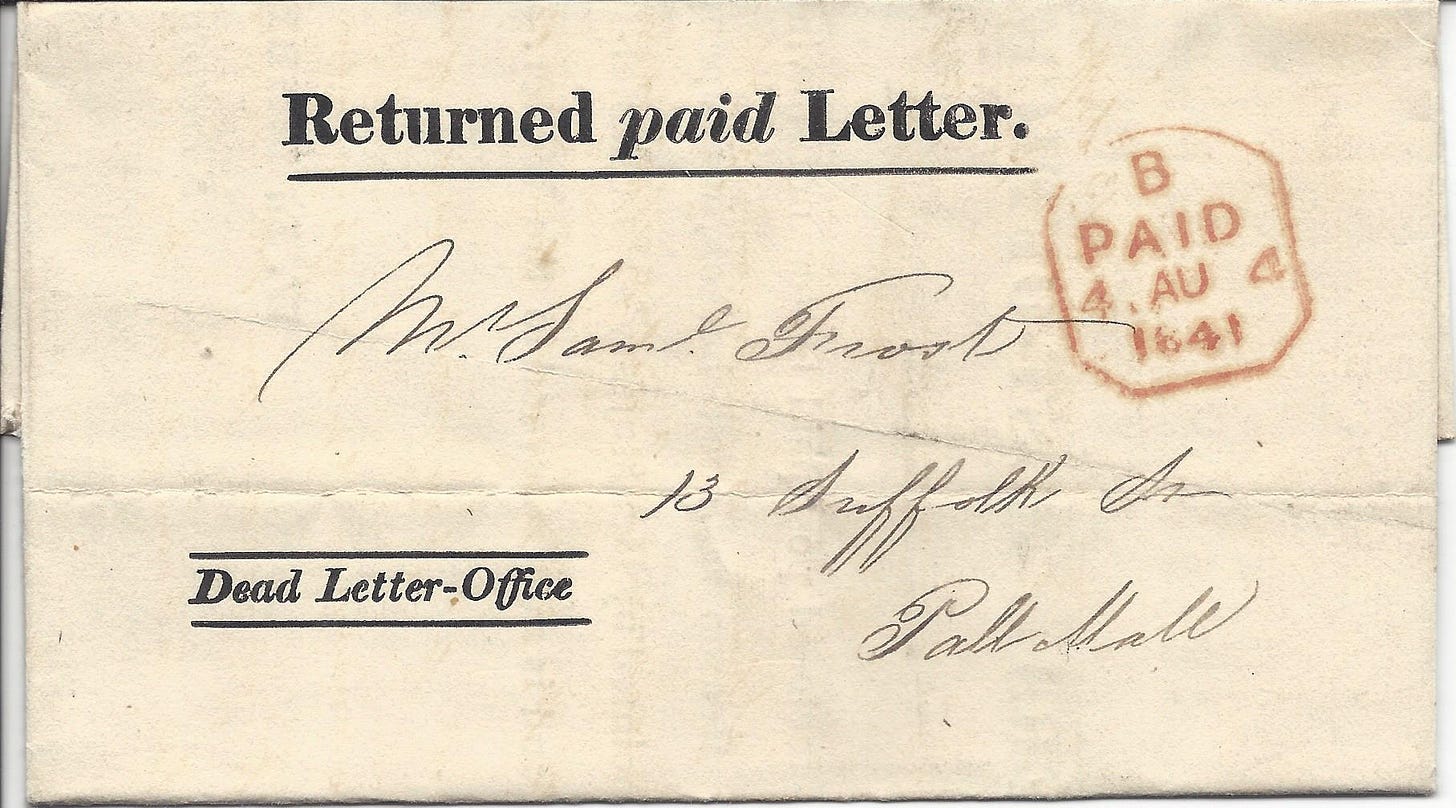

The first item in today’s Postal History Sunday is a folded lettersheet that was used as a wrapper. It was mailed on August 4, 1841, from the London Dead Letter Office to Samuel Frost at 13 Suffolk Street near Pall Mall. The inside of the wrapper includes a pre-printed notice that the contents in the wrapper had been returned to Frost because they could not be delivered. The reason for the failure to deliver would have been marked on the original letter and could include descriptions like “refused” or “unclaimed.” Sadly, we don’t have the original letter, so the trail of clues stops here and we can’t be sure what was returned or why it was returned. But, we’ll have another opportunity to see what this looks like with another example.

Now, before we go much further, we need to consider the importance of mail as a method of communication and as a mode to transport business papers and other valuable matter. Postal services could not just throw up their hands and say, “Well, I guess we’ll just burn this piece of mail because we couldn’t find the recipient!” Instead, they had to try to put in the effort to find the intended recipient. Or, failing that, they had to determine the location of the sender so they could return the item to its origin.

Typically, this required that workers in the Dead Letter Office open the piece of mail in an effort to find out where it came from. If a sender and location could be identified, the letter could be returned under a separate cover - just as this item was sent back to Samuel Frost.

“The Dead Letter Office was established in London in 1784 to deal with dead and missent letters, when the addressee could not be found. Similar offices in Edinburgh and Dublin opened shortly after. In 1813 a Returned Letter Office was organised to return undelivered letters to writers and collect the postage due. Prior to 1813 the only letters returned were those supposed to contain money or items important enough to escape destruction. During the 19th century the department for dealing with undelivered and returned letters was variously named the Dead Letter Office, Dead and Returned Letter Office and Returned Letter Office. In 1854 it became a branch of the newly formed Circulation Department. By the early 20th century the work of headquarters offices was devolved to separate Returned Letter Offices set up in major towns in Britain.”

from the London National Archives, viewed July 12, 2024

Since our first piece of postal history is addressed to a letter in London and the red postmark on the front of that folded letter is a known London marking, we know that it was sent by the London DLO rather than Dublin (Ireland) or Edinburgh (Scotland).

Dead Letters - Three Decades Later

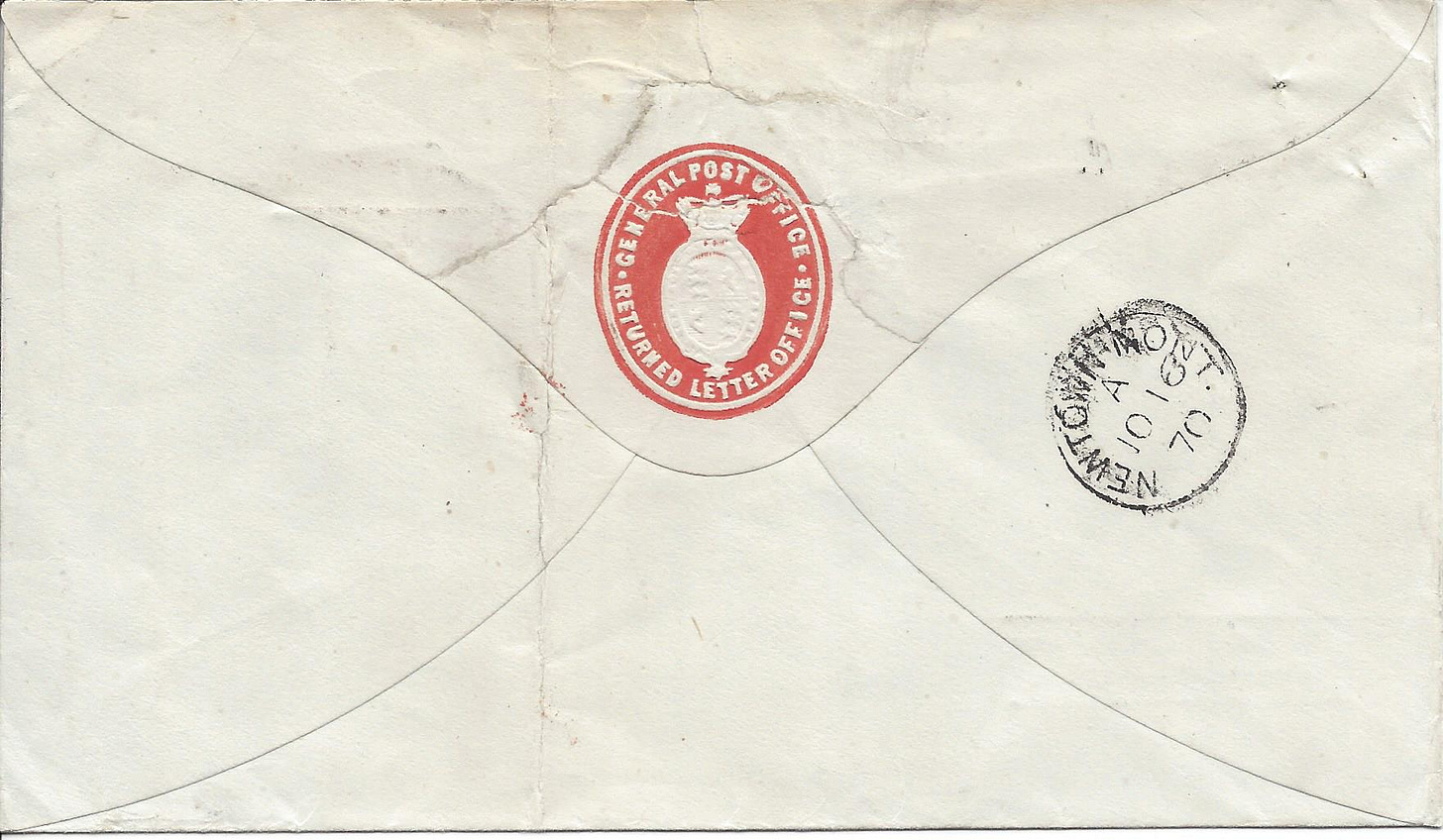

If we fast forward from 1841 to 1870, we see that some things have definitely changed when it comes to dead letters and the British Post Office. First, the name has been adjusted to the “Returned Letter Office.” And, second, an envelope, instead of a folded lettersheet, has been used to carry the piece of mail that could not be delivered.

Like our first item, this envelope clearly states that the content being sent back was a “returned PAID letter.” Items that had been sent unpaid would, obviously, not include these words. And, an amount due would be placed visibly on the envelope so the clerk in Newtown would know to collect the postage.

The returned item came from Williams, Gittins & Tomley, solicitors, in Newtown - a settlement in Montgomeryshire, Wales. So, the outside envelope is addressed to them - even if Tomley doesn’t appear on the address line. Perhaps Tomley had not yet joined the firm? Or maybe this is just an illustration of the hazards of being the third name in a business partnership.

The flap of the envelope bears an embossed design that reads “General Post Office - Returned Letter Office.” This refers to the General Post Office at St Martins le Grande in London and tells us the letter was processed at the Returned Letter (or Dead Letter) Office found there. We also have a November 16, 1870, date for its arrival at the Newtown post office.

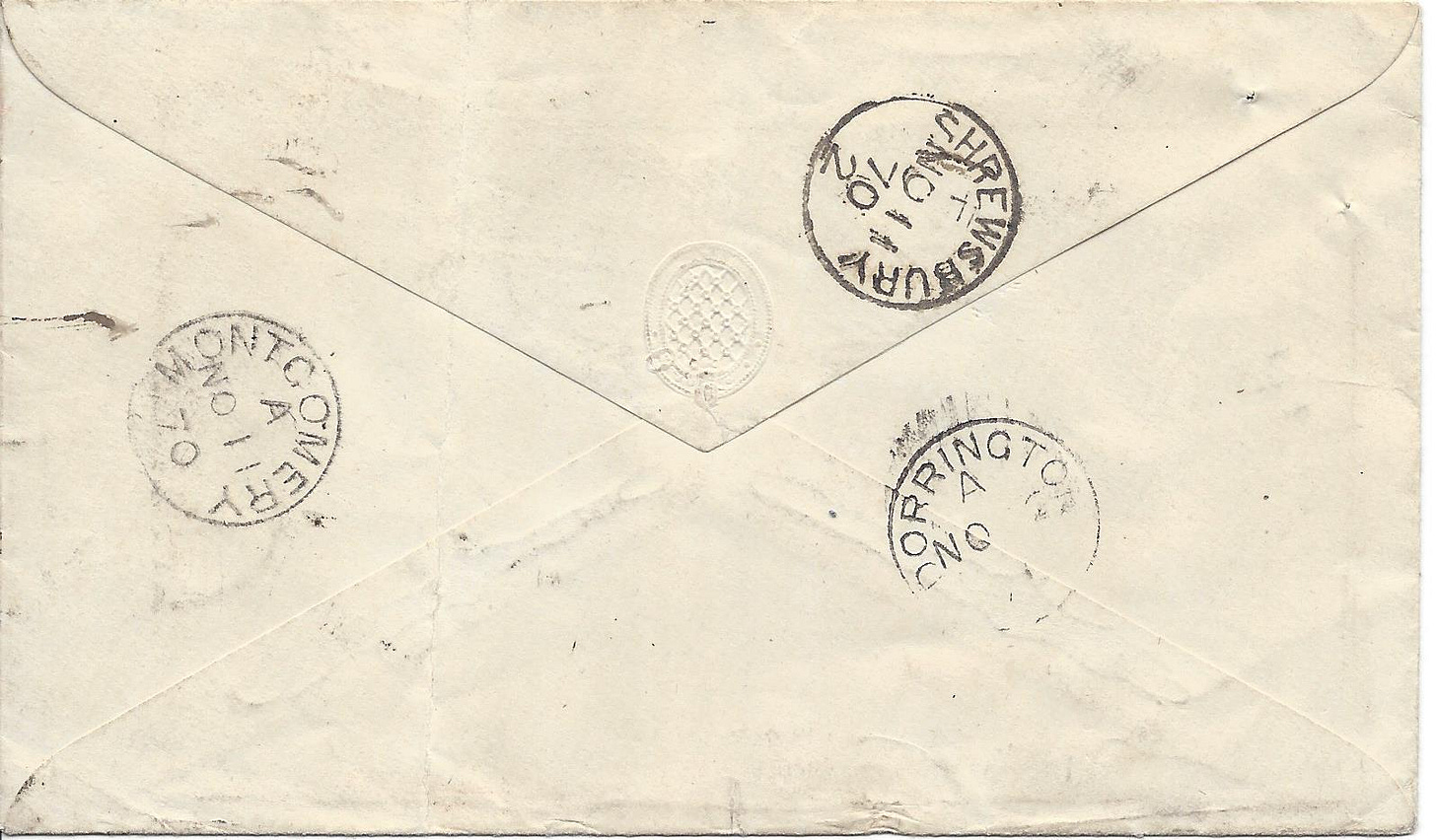

And another thing we have is the envelope that was returned to Williams, Gittins & Tomley! So, unlike our first example, we can actually see the reason why this letter was returned to its origin.

Once we see the piece of mail that is being returned, we can immediately understand why it was not delivered. The words “dead” and “deceased” were written on the envelope to provide an explanation for failed delivery. We appear to have a dead letter in more than one sense of the word!

The recipient “Eyton Esquire,” apparently didn’t rate a first name on the address. However, it is possible the senders were aware something might be going on because they placed the docket “to be opened in his absence” at the top - effectively giving permission to someone else in the household or business to view the contents. Apparently, there wasn’t anyone who felt authorized to open Eyton’s mail (despite the docket) and the item was forwarded to London and the Returned Letter Office.

The intended recipient was quite possibly William Eyton, a land valuer who was active in the 1840s according to this record in the UK National Archives. They resided in Gonsall (or Gonsal), a farm or small community, near the town of Dorrington, south of Shrewsbury (in England), and only 35 miles away from Newtown.

The reverse of the envelope to Eyton shows us the story of its travels. The first postmark is Montgomery (northeast of Newtown and in Wales) and is dated November 11. The second is Shrewsbury (Nov 11) and the third is Dorrington, the small town that was closest to Gonsal. This last postmark is dated November 12.

If you scroll up to view the image of the front of this envelope, you will see postmarks for November 13 in Shrewsbury. This gives us evidence as to when the letter was sent to the Returned Letter Office in London.

Clearly it did not take the Returned Letter Office long to figure out where to return the letter. While I do not have the contents of this envelope, we can make an educated guess that it held a business correspondence that clearly gave the details for William, Gittins and Tomley. The November 16 date on the outer envelope shows it got back to its origin only three days later!

It’s at this point that I remind myself that I’ve had more time to think this through than you have. So, if you didn’t follow my first effort to explain the travels of this letter, try this:

Williams and Gittins of Newtown, Montgomeryshire in Wales sends a letter to William Eyton on November 10 or 11.

The letter is processed in Montgomery, Wales on November 11

The letter travels to Shrewsbury, England and arrives on November 11

The Shrewsbury office sends the letter out to Dorrington on the morning of the 12th and delivery is attempted.

Discovering (or already knowing) that Eyton is deceased, the letter is returned to the Shrewsbury office.

Shrewsbury sends the letter on to the Returned Letter Office in London on November 13 - probably with other dead letters.

The Returned Letter Office quickly determines that Williams and Gittins in Newtown were the senders of this letter. That office put it into a slightly larger envelope and mailed it to Newtown - on Nov 15 or early on the 16th.

The letter gets to Newtown on November 16.

Want to learn more?

The concept of dead letters and the Dead Letter Office is not new to Postal History Sunday. A fairly recent entry (#187) decodes the journey of the cover shown above. And we even got to learn more about dead letter mail in the United States with PHS #165 (Humbug). If you don’t get enough Humbuggery there, you can find more information about that particular topic here - you just have to scroll to the middle if that’s all you want to read. Finally, there is one more titled Not Called For that deals with a dead letter that originated in France and went to the London Returned Letter Office.

For those who are interested in getting deep into the details for British dead letters, a book by Snelson and Galland, The Returned Letter Offices of Great Britain to 1912 and Beyond, might be of interest to you.

And, if you have a taste for seeing a group of US dead letters from the 1880s, the Smithsonian National Postal Museum has a page that highlights the Dead Letter Office Blind Reading Album. The covers in this album illustrate a whole host of reasons why a letter could not be delivered and include the reasons for failed delivery written on each. I noticed one cover that was addressed to Cornell, Iowa that was probably intended for Cornell College in Mount Vernon - unless it really was meant for Cornell University in Ithaca, NY.

Thank you for joining me today. Have a fine remainder of your day and an excellent week to come.

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack. And, some publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest.