Welcome to Postal History Sunday!

This week, I thought I would start by answering a question that I know has been asked (and maybe even answered) in one form or another over time. But, after last week’s entry titled Swiss Missed (PHS #225), I got two questions asking how long it took me to compile the information and create the resulting article.

First, let me respond with a big “thank you” to those who took note that last week’s article seemed to have a bit more work required than some. It did, in fact, require more time and effort than many PHS entries. I have known I wanted to write the Swiss Missed article for over a year now, which means I have looked for information on and off for about that long. But that part of the research was usually cursory and its permanence was fleeting. I suppose it would make sense to call it “scouting in advance.”

Things I find early in the process don’t always get properly tagged or noted for easy recovery later on. So, I often end up going through a process of rediscovery when I get more serious about completing the article. The good news is that I tend to find materials much more quickly the second time because I have ideas about what to look for and how to find them. And, I’ve had time to think things over! That counts for something, but it’s hard to enumerate how much effort that “thinking” takes.

The work during the week prior to publication probably required somewhere in the neighborhood of eight hours on the Swiss Missed article. Clearly, that is not a sustainable level of commitment every week. I do have other things on my plate that regularly clamor for my time and attention. Hopefully this explains why I sometimes engage in “rewrites” or articles like the one that follows.

Today, I’m going to share some items where I have only partially explored the story they bring with them. In effect, you are witnessing future Postal History Sundays in the exploration process. For many of them, I do know much more than I am sharing today, but I’m just not ready to write about the rest. In some cases, I have only begun the process, but I have ideas as to where I am going next. And in one instance, I’ve already used the item in another PHS, but it may show up again!

I hope you enjoy this peak into the process and maybe we’ll all learn something new while we’re at it!

When one isn’t enough, two will do

This first item is an attractive (to me at least) item that was mailed at Cambridge (Mass) on January 25, 1869. It’s eventual destination was the city of Rosario in Argentina. The 34 cents in postage stamps properly paid the rate per half ounce, of which 24 cents were passed to the British Post (note the red 24 at bottom right).

The interesting thing about this cover from the postal history perspective is that it did not take a steamship directly from the US to Argentina. Instead, it crossed the Atlantic Ocean - twice! The first trip started on the 26th in the New York Harbor and the second headed back west from Europe to South America.

Direct mail service to the East coast of South America from the United States was a fairly new concept in the 1860s. Prior to that, letters from the US relied on the British Mails to get letters there. Sometimes, the fastest route via British mail (due to sailing schedules) was to cross the Atlantic two times - just as this one did.

The pre-printed address panel on the envelope is also rather eye-catching. While pre-printed envelope were not unheard of in the 1860s, it was far less common than hand-written addresses and directions. As a result, this cover practically begs the question “who or what was Wheelwright & Co?” And, needless to say, the answer would be a part of the final project.

This is a case where there is so much information that the real work will be in selecting enough - but not too much - for a proper PHS article. Someone else has already written the book on William Wheelwright, so there is no need for me to do that! (J.B. Alberdi’s work in 1877 is here) The short (and very incomplete) answer I will share today is that William Wheelwright was a US businessman based in Rosario during the last 1860s. He was involved in developing railways in Argentina and also helped establish a steamship line on the West coast of South America.

The letter itself is sent to George L. Windsor, who was likely traveling in South America and was using Wheelwright and Company as a mail holding or forwarding agent. Windsor likely also held a line of credit with Wheelwright to facilitate travel. Other than this, I have found nothing specific about the addressee. However, strategies to locate Windsor could include genealogy sites, historical sites focused on Cambridge or Rosario, and maybe even a mention in sources focused on Wheelwright.

We’ll see what I come up with at some point in the future - that could be a few months to a year from now. I am never sure how these things will progress.

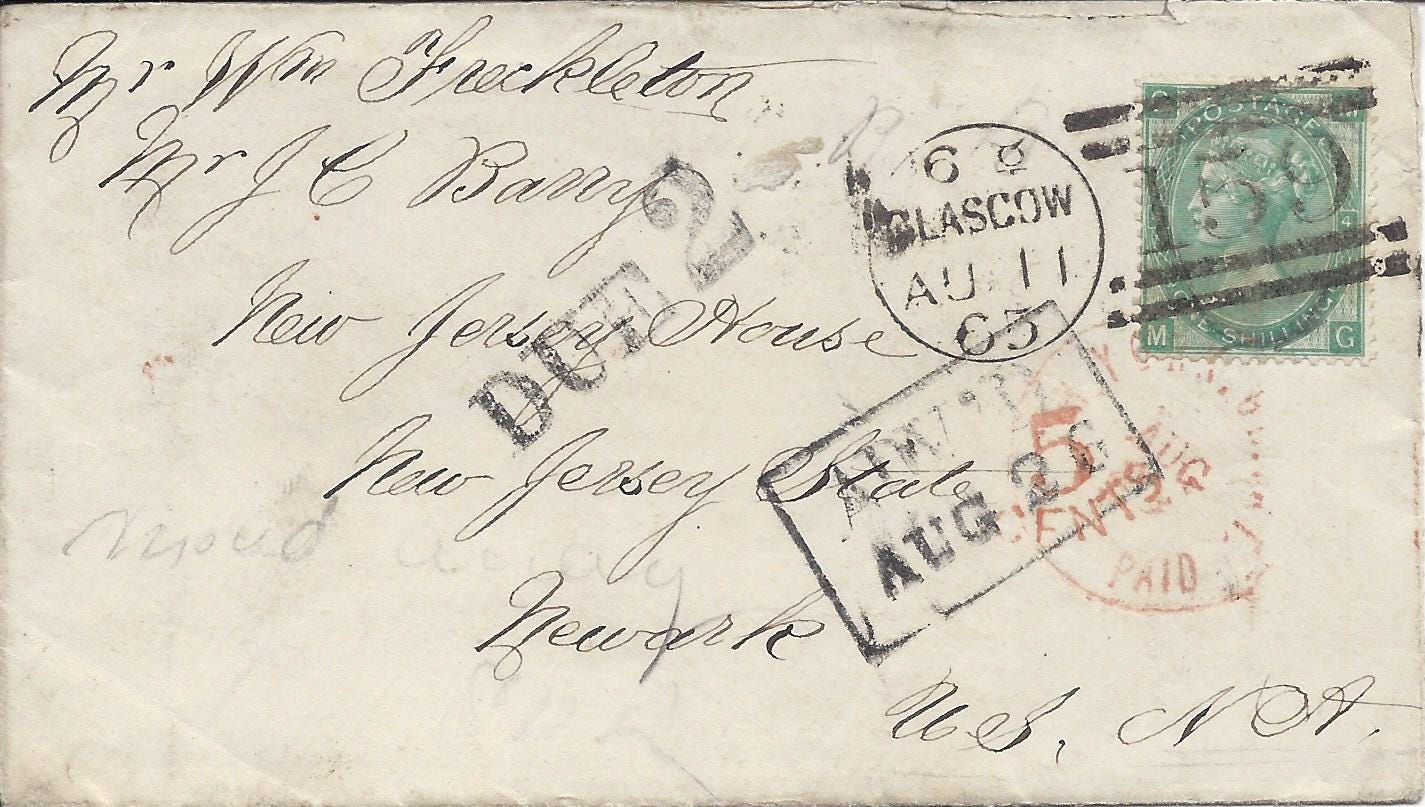

Surely there is more than one house in New Jersey

The next item would be a nice addition for the Exceptions to the Rule article (PHS #217). While it is an example of the 1 shilling rate for a simple letter from the United Kingdom (Scotland) to the US in 1865, it also has a little bit extra to offer. The big rectangular marking reads “ADV’D Aug 26,” which tells me that the letter was advertised in the paper in hopes that the recipient(s) would come pick up the letter at the post office. The cost of this additional service was two cents - hence the “Due 2” marking on the front.

While that is interesting all by itself, I feel like there is something worthwhile to pursue on the social history side - if only I can tease it out. My suspicion is that William Freckleton and J.C. Barry were immigrants from Scotland whose initial stay in the US might have been at a place called the New Jersey House. When an attempt was made to deliver the letter, it was found that the addressees had “moved away” (see the pencil marking at bottom left). This led to the advertisement in the paper, which failed to find either person.

My first direction of inquiry was to see if I could identify the “New Jersey House.” It is, unfortunately, a singularly unhelpful designation (my opinion) that has gotten me nowhere thus far. But, these things can take time. So, I will stew on this a bit and inspiration may hit for another angle to try and find an answer on that front.

My second approach was to see if I could find mention of either addressee. I am armed with an additional piece of information. The letter came from Glasgow, Scotland. This is a good indicator that these men were Scottish and had friends, family, or business partners back in Glasgow. The feel of this item is that it was personal correspondence rather than business.

Sure enough, when I did some looking around, I found many individuals with similar names that were either in Scotland or in the US and from Scotland around 1865. Unfortunately, I don’t have enough of a match to claim success.

On the other hand, there is a reasonably good chance that Freckleton and Barry were involved in or part of the mass export of the poor from Scotland during the tail end of the Highland Clearances. This was a period of time when land owners actually paid passage to send the poor overseas rather than be responsible for their care. For now, I will refer you to the wikipedia page if you wish to learn more - this page is well done with excellent citations as far as I can tell.

If I can find a solid connection with the addressees, this would be a fine Postal History Sunday on its own.

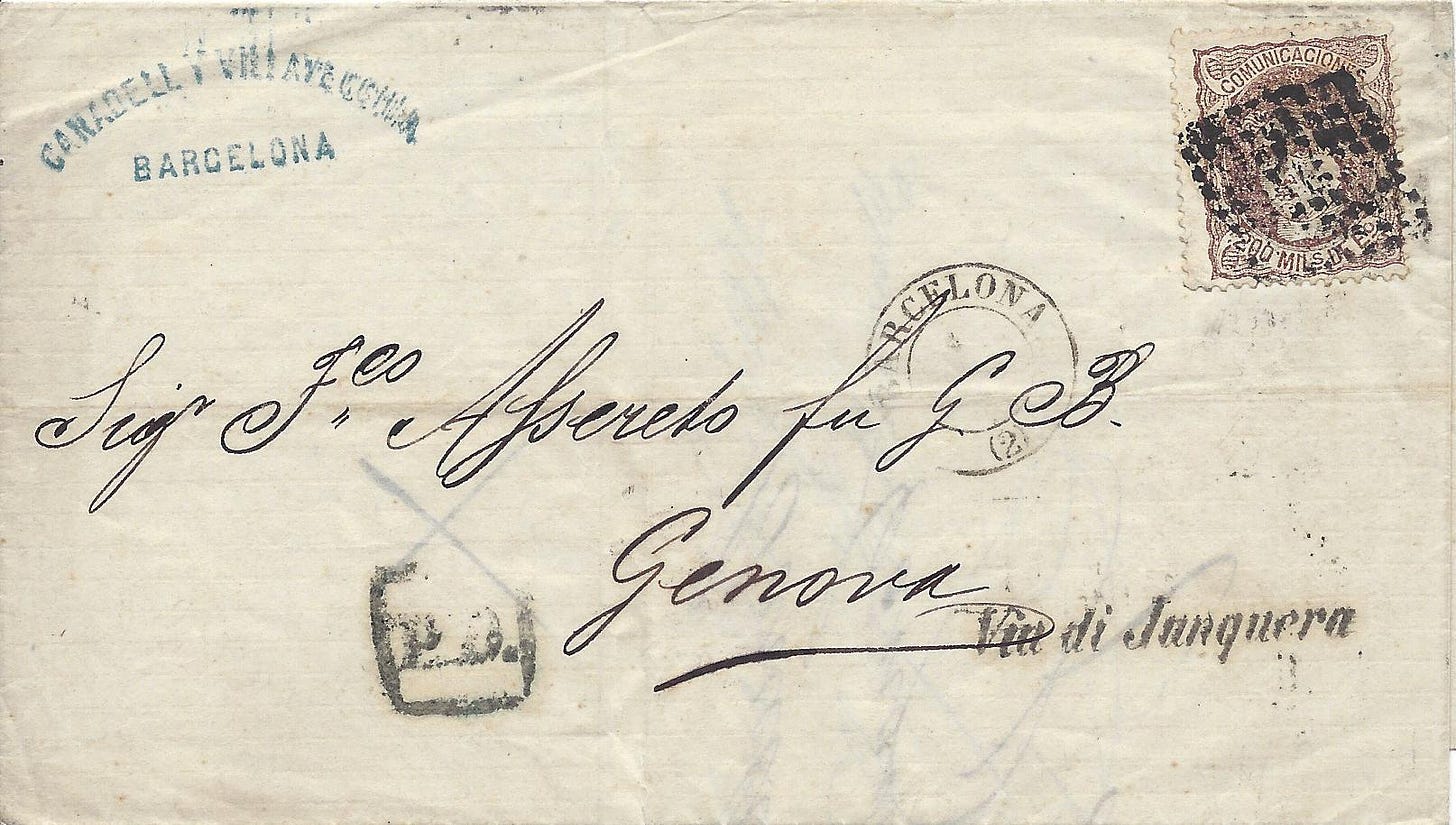

Not built in a day

Our next item is one that I’ve explored on and off, but haven’t really made the connections that have encouraged me to do an in-depth analysis. Instead, there is one thing that grabbed my attention which led to learning something about the old Roman roads.

At the bottom right, you might notice the marking that reads “Via di Junquera,” which is a route marking that indicates where it was to cross the border between Spain and France. In the 1860s and 70s, there were two main crossings for mail to travel (unless the origin and destination were very near the border). The Western crossing was at Irun (Spain) and St Jean de Luz (France). The Eastern route went through a pass in the Pyrennes at La Junquera (Spain) and Le Perthus (France).

Now, before I go much further, I need to remind me (and all of you) that when I see “via di Junquera” on this envelope, it tells me the letter was to travel USING this route (or VIA this route). But, now I’m going to reference the Italian use of “via” that means “road” or “street.”

The pass at La Junquera was the western terminus of Via Domitia, an old Roman road that connected Spain to Italy by traveling through southern France. It connected with Via Augusta, which went south into Spain. Via Domitia’s construction began at roughtly 120 BCE and Via Augusta began around 100 years later. As a point of interest, a section of Via Domitia was rediscovered in southern France in recent years.

Simply put, I find it interesting that this letter, mailed from Spain to Italy in 1872, roughly followed the routes of Vias Augusta and Domitia to get to its destination - Genoa, Italy.

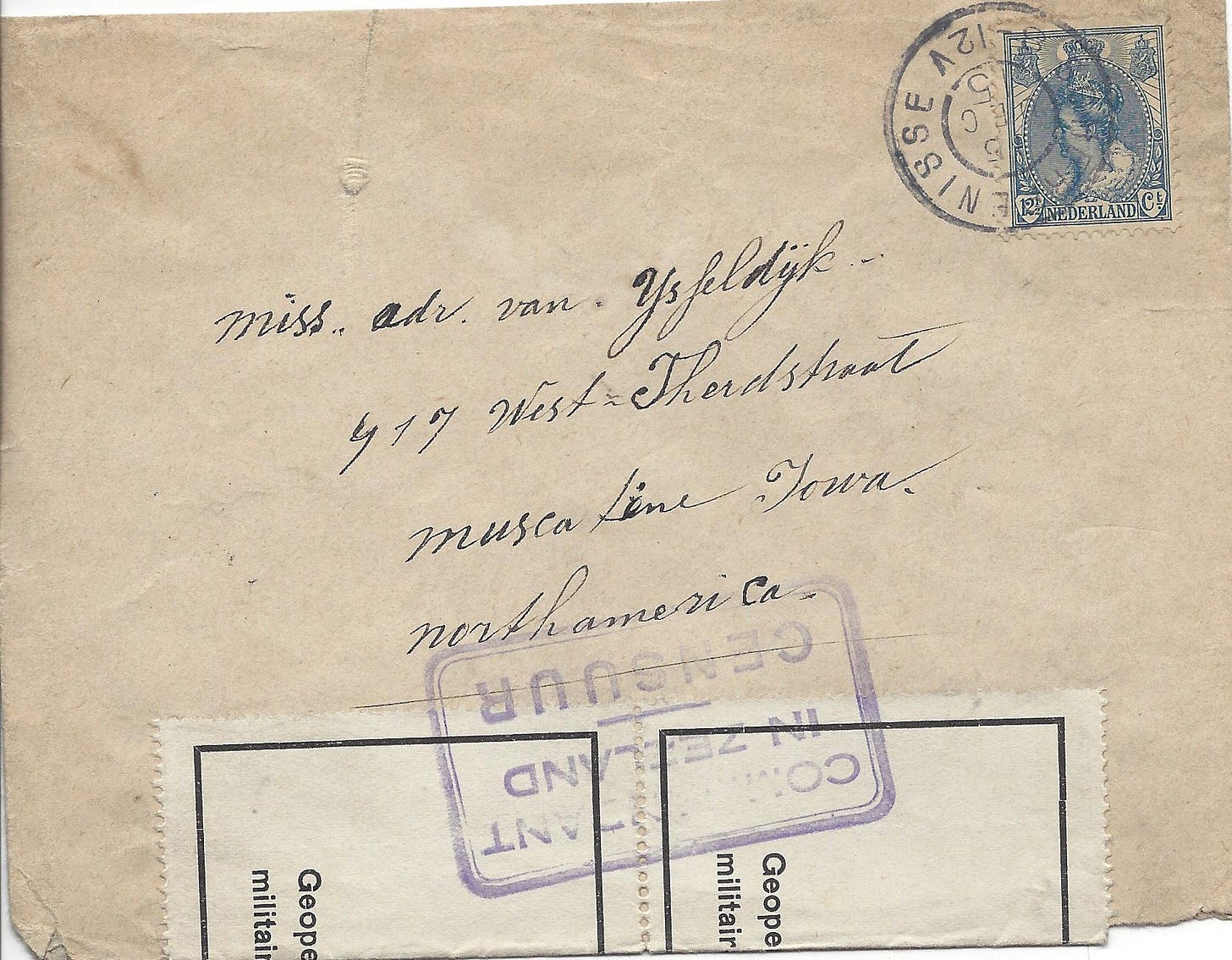

Patiently waiting for an ounce of attention

I will admit that covers from the 1850s through 1870s tend to get my attention first because I am most familiar with them. That’s what happens when time is limited. Sometimes, you just can’t dedicate the resources to swim in unfamiliar waters.

This cover was sent during World War I from the Netherlands to the United States. It was opened and inspected in Zeeland (the Netherlands) according to the purple marking that appears on both the front and the back. Two labels that had adhesive were used to seal the bottom of the envelope back up before the letter went on its way to Muscatine, Iowa.

And now you know why this particular cover got on my radar in the first place. It landed in Iowa, my home state.

While I won’t tell you much else about it at this time, I will point out the address - 417 West TherdStraat. It’s another fine example of an item that could have been featured in PHS #209, What’s in a Name. The writer of this letter did make an honest attempt to write it as a person in the US might expect to see it. “Therd” is probably an attempt at “third,” but they mixed that with “derde” (third in Dutch). They gave up and put the word “straat” instead of “street.” If only I could do as well writing a Dutch address for an item I was sending to the Netherlands!

Maybe they should gone for a big Postal History Sunday twist and used “via” instead of “straat?”

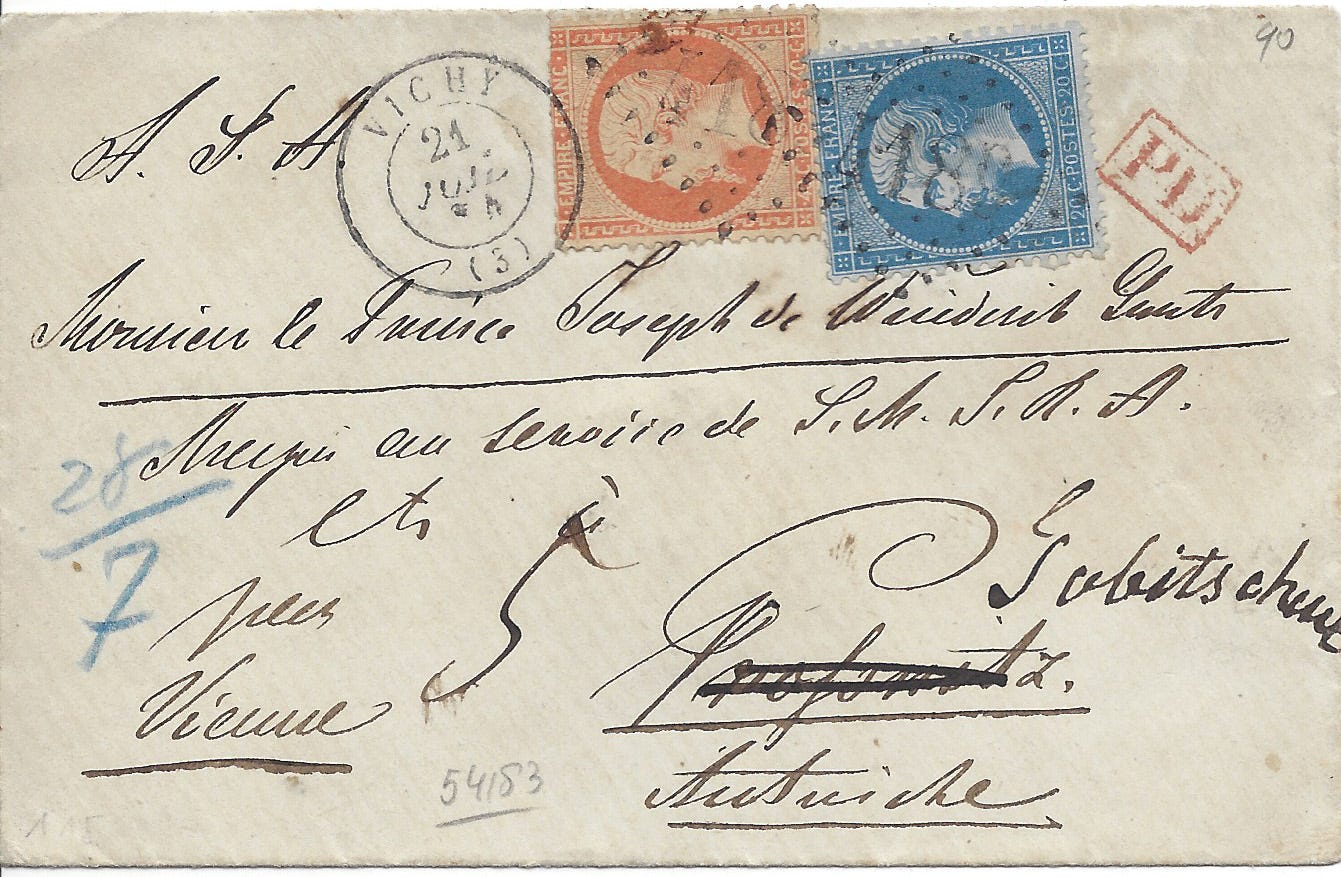

Can’t we just say something like “you’re great, now read my letter?”

And here’s an item I have discussed in a prior PHS from February of 2023. But, to make it easier for you, I condensed the description here:

This letter was mailed in the mid-1860s from France to Austria. The postage rate was 60 centimes, which is properly paid by the postage stamps. All of the markings for a typical, paid letter from France to Austria can be found on this letter. But, there is an ink scrawl that is the number "5." This told the letter carrier to collect 5 kreuzer from the recipient on delivery because the letter had been forwarded, which required more postage.

However, the part I wanted to share today is a quick look at the address panel and the addressee:

A.S.A.

Monsieur le Prince Joseph de Windisch - Grätz

??? au service de S.M.T.R.A.

With much appreciated help from Ralph on the German Discussion Board, I can share some of the meaning of this address.

A.S.A. (A Son Altesse or To His Highness)

Monsieur le Prince Joseph de Windisch - Grätz

??? au service de S.M.T.R.A. (Son Majeste Titulaire Royale Altesse or His Majesty Royal Highness)

And there he is, in all of his high and mightiness! After seeing this letter with his grand titles all nicely turned into an acronym, it wonder… Do the abbreviations of the titles (except Monsieur le Prince) tell us a little bit about the frivolous nature of honorifics when it’s just an envelope that traveled through the mail - possibly next to a letter from and to a “commoner?” Inquiring minds want to know!

Or maybe I just like ending with a small amusement.

Thanks for joining me today. I hope you enjoy the holiday season in whatever way is appropriate for you and yours.

Thank you for reading Postal History Sunday! Have a fine remainder of your day and an excellent week to come.

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack. And, some publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest.

Rob —

Thanks so much for giving us not the normal one or two items to drool over but today you gave us five!