This weekend has traditionally been a big weekend on the farm for getting crops into the ground. We should be past a significant risk of frost and we really can’t wait much longer if we want a good harvest in 2025.

Since that is the case, I’m going to do a “free form” Postal History Sunday this week and just see where it goes. Essentially, I’ll start with a cover, share a few things about it with you and see what it makes me think of as I work on that part of the article. Usually, it becomes clear to me as I write about one item what I should move to next.

I’ve gotten a good response with this approach when I’ve tried it out in the past. So, it’s time to stuff those troubles into a laundry bag. Take them down to the washer and run them through either a hot or cold cycle, depending on your mood. While they’re getting dizzy in the washer’s spin cycle, grab yourself a snack and a favorite beverage. Put on the fuzzy slippers and sink into a comfortable chair.

It’s time for Postal History Sunday!

Ugly, but interesting

Given the choice between a dirty, torn and wrinkled cover and one that is clean and has clear postal markings, I would usually find myself inclined to prefer the latter. Except, there are times when ugliness is a signal that something interesting is going on. And I very much appreciate it when a good story comes along for the ride with a postal history item.

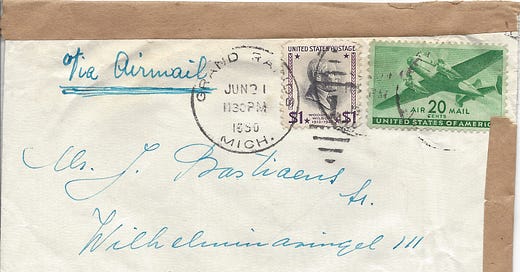

The tattered envelope shown above was mailed from Grand Rapids, Michigan (USA) in June of 1950. The total postage applied was $1.20 in an effort to get the letter to its recipient in Maastricht, Netherlands. The postage rate for letters sent by air mail to Europe was 15 cents per 1/2 ounce in weight (Nov 1, 1946 - Jun 30, 1961). That means this was a heavy letter weighing more than 3 1/2 ounces and no more than 4 ounces.

To give you some idea, about 5 sheets of regular 8 1/2 x 11 printer paper would weigh one ounce, so 18 sheets of paper would get us to the weight required for this postage level. I am not, however, suggesting the contents of this envelope was all paper. I suspect there was something else that was probably not paper that made this letter heavy.

One clue I used to come to this conclusion is the brown tape that can be seen at the top and the side of this envelope. Clearly, the envelope had difficulty holding together in the mailstream. Now, I can’t be sure if that was damaged by accident or on purpose. I can only say that it was damaged.

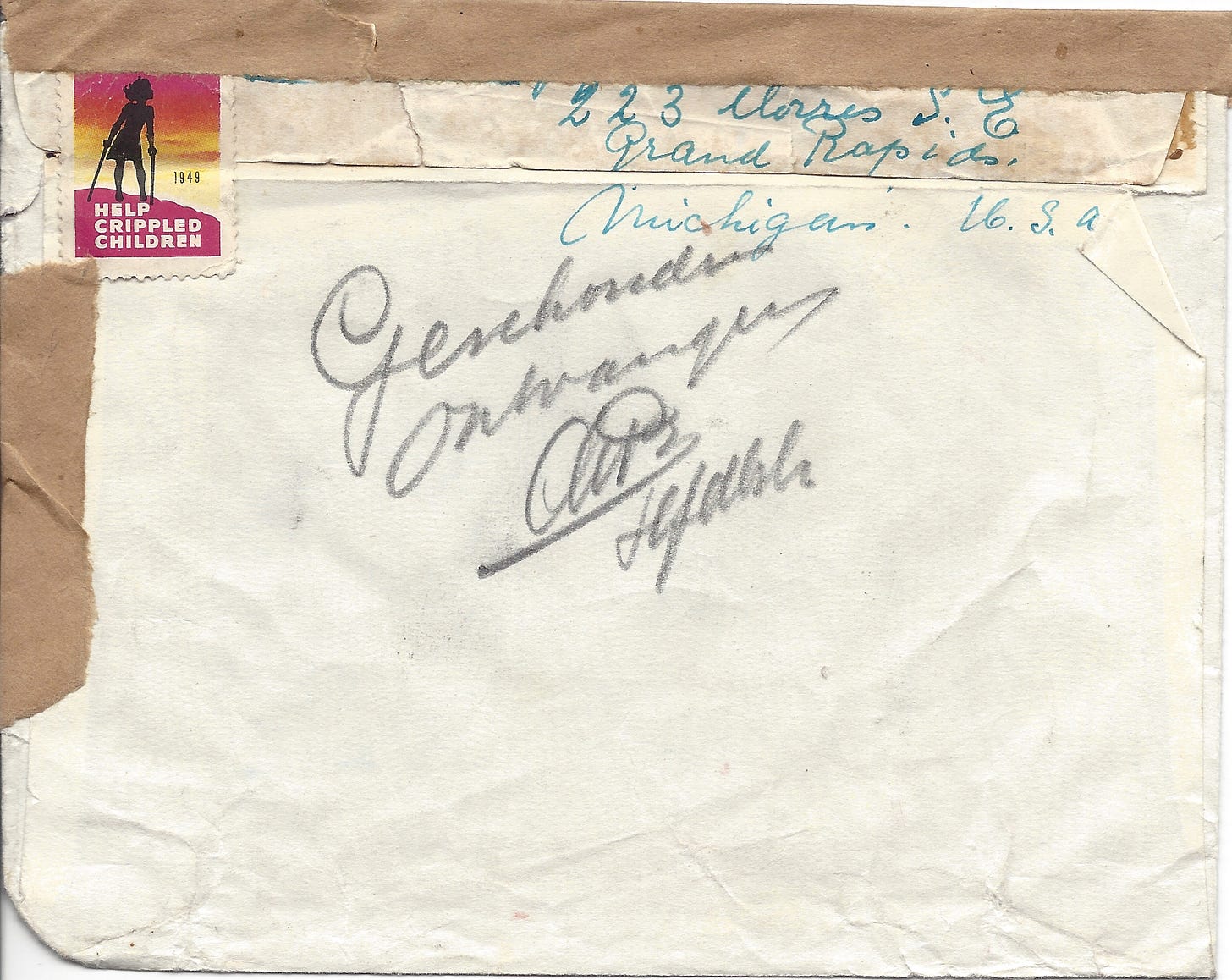

The back of the envelope provides us with an additional clue. There is a pencil marking that reads “Geschonden ontvangen.” With the help of Ralf Reinhold and Kenneth Bryson, I can now tell you that this letter was “received damaged.” My initial attempt at figuring this out utilized online translation tools. I thought the words were “Geschenden onwanger,” which translated to “violated with consent.” While I suppose that could have been the case, I much prefer the less violent and provocative “received damaged.”

I presume the rest of the pencil marking is a signature by the postmaster of the Maastricht post office. Perhaps the first part are initials and the second could be a title, but I can’t decipher it. If anyone out there can help with this, I would appreciate it. It just doesn’t feel like I’ve done this up right if I can’t figure that out as well.

Whether I can decipher the whole thing or not, we can deduce that this letter broke open (or was illegally opened) as it traveled through the postal service. The receiving postal clerk in Maastricht (or somewhere along the line during the travels this letter took) documented on the envelope that it arrived at their office in this condition. I presume the person who wrote this explanation also applied the brown paper tape to reseal the envelope.

The next question that comes to mind is one I will never be able to answer: Was everything still in the envelope when it was resealed? If the letter had been registered, the weight of the postal item would have been recorded and probably checked to determine if it was lighter. But since this item did not include that special service, no effort was made to determine if the letter still held what it was supposed to.

We will also never be able to state with any certainty what was sent in the envelope. However, I think we can come to a valid supposition that the contents were perhaps a loose, hard material that was shifting around in the envelope and could very well have worked through a weak spot. Perhaps there were a few coins rattling around in there? Could the promise of something valuable have tempted someone to to encourage this envelope to open a bit more?

Speaking of a weak spot in the envelope. You might have noticed the colorful Easter Seal at the top left that is strategically placed to help hold the envelope flap down. Both Christmas and Easter Seals were charity labels that were often used on items sent through the mail. While they were often simply decorative, many people used these adhesives to help keep envelopes closed.

A bit more about envelope flaps

I did warn you that this week’s entry was just going to go in whatever direction seemed right as I went. We were talking about holding envelope flaps down, which made me think about this interesting cover that was mailed from the United Kingdom to Milan, Italy.

Unfortunately, the postal marking is not clear enough for me to determine a date, but the postage stamp features King Edward VII and would most likely have been used during or just after his reign (1901-1910). At this time, the letter rate was 1d (one penny) for a letter weighing up to four ounces in weight. However, the special Book Post rate applied here because this item weighed less than two ounces. So, a half penny stamp properly paid the postage required (Oct 1, 1870 - Oct 31 1917).

The Book Post was introduced by Rowland Hill in 1848 in an effort to aid library circulation. Initially, it was intended only for packages holding one book at a time. This rate was soon extended to include any printed matter. To qualify, there could be no personal messaging or letters included and the package had to be easily opened for inspection. This particular item probably carried some sort of pre-printed advertising circular.

This envelope design was created and patented by Cannon, Barrett & Company at 12 Harp Lane in London. The tab at the side was intended to be tucked in rather than using gum to seal the envelope shut. This would allow the postal clerks to open the envelope for inspection and then close it back up so it could continue its journey to the destination address.

Another example of a Book Post patent envelope from this company is shown above. In this case the extended flap area that has the envelope maker’s address was intended to be tucked in to hold the contents securely during transit.

After a brief search, I was unable to find resources that provided a history for this company. On the other hand, I was able to find artifacts that were made by them. For example, I did find a 1904 horticultural field diary by Ernest Henry Wilson that used a book manufactured by Cannon, Barrett & Co. The inside of that cover with the maker’s label is shown below.

This is one of those strange coincidences that happen when I least expect it. As a horticulturist/farmer/food grower it’s hard to ignore the fact that one of the few web references to Cannon, Barrett & Co was for a notebook that holds notes about plants. Plants in China, but plants nonetheless.

It just so happens I do a fair amount with plants. Therefore…

The seed is planted

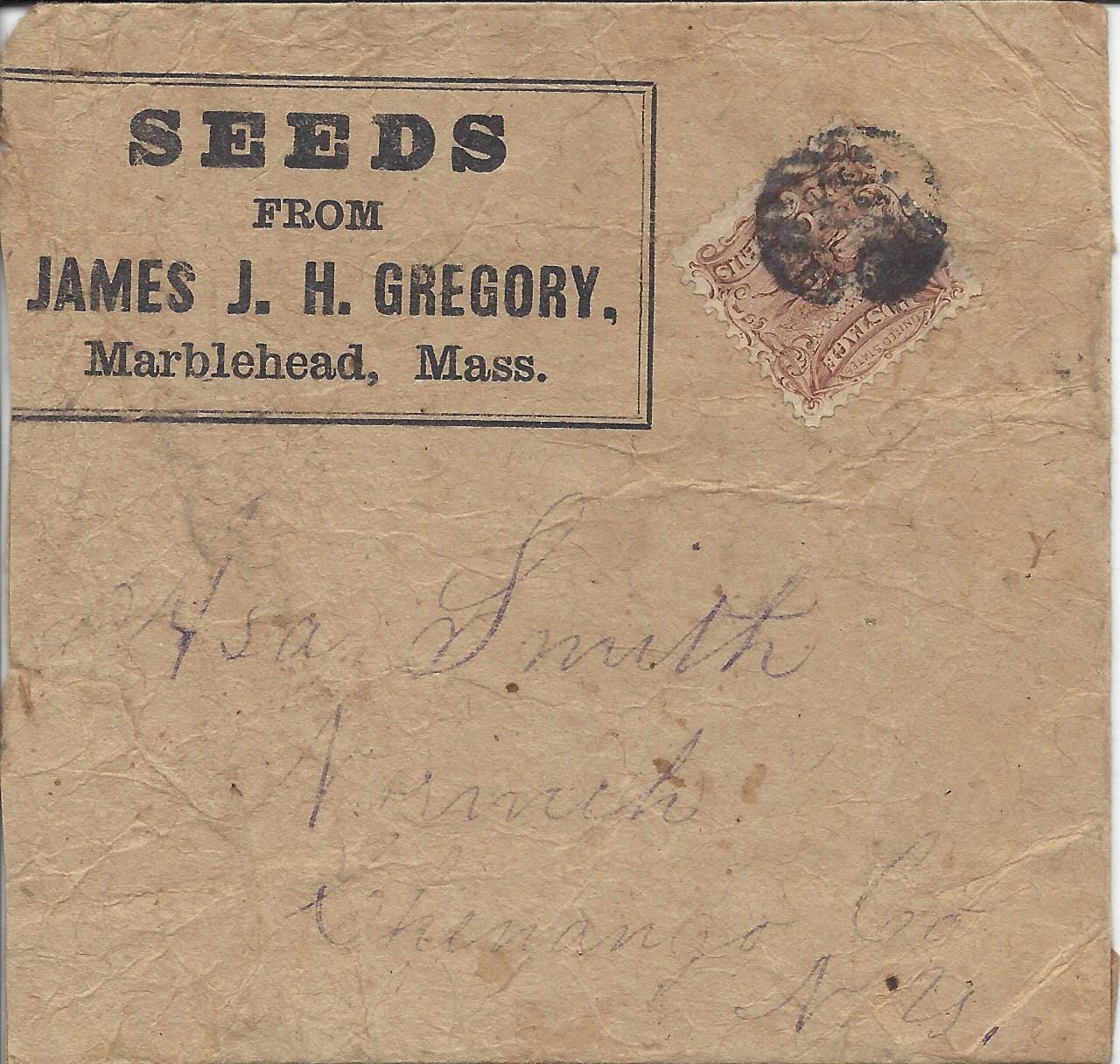

Since I started talking about plants, I guess I should show an envelope from 1869 or 1870 that probably carried seed from James J.H. Gregory’s seed business. This is one of those covers that I keep wanting to write about, but when I get started the task grows beyond the time I have to complete it.

For those of you who enjoy “behind the scenes” glimpses into how Postal History Sunday is created, I think this is an excellent opportunity. For those who don’t - now is a good time to skim!

There are some covers that I feel like I want to give the item the full treatment. And when I say, “the full treatment,” I mean that I see lots of potential to explore the item from both postal history and social history angles. The problem with potential is that it usually takes significant time and effort to bring that potential to fruition. It almost certainly will take more time than a few hours on a Saturday evening to write something that will make me feel good about what I’ve presented. And it is definitely more than I can spend on a “let’s see where this goes” article.

Therefore, articles for covers like this end up getting handled in one of two ways. Sometimes, I scribble or type out outlines and hunt for resources over a period of years - but I never share my progress until I feel pretty good about what I have. An excellent example that shows the results of this process is the Train Came to Street Road, PHS #240. While I still feel that article could do with a bit more editing and maybe another tidbit or two, I’m pretty happy with it. And gauging the response, so were many of you!

With this cover, I’m taking a different approach. It has already appeared in a 2023 PHS with a brief cameo. And here it is again. I offered very little detail the first time. But this time, I’ll share a little more.

The good news is there is a book dedicated to telling the story of James J.H. Gregory. Written by Shari Kelley Worrell in 2013, Remembering James J. H. Gregory: The Seed King, Philanthropist, Man, looks like it would have far more than I would need for a single article. Worrell is also responsible for co-authoring a timeline for Gregory’s life, which would probably give me enough for a good start.

But how do I say “no” to a whole book of information on the topic? Sometimes the limits placed on my by available time lead to decisions I don’t particularly like.

Which means it’s time to show you a picture of vegetables we’ve grown on our farm.

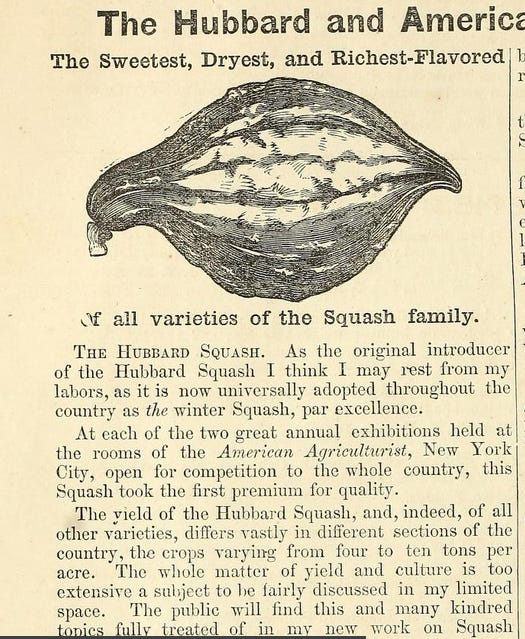

The introduction of Hubbard squash to the seed industry is attributed to Gregory and, as the story is told, it was this squash that led Gregory to a successful seed business. While there is no way to know, it is possible this envelope carried some Hubbard squash seed to Asa Smith.

Just the idea that this envelope carried squash seed through the mail 155 years ago makes me happy. I can almost picture Asa Smith opening the envelope and placing a few of the flat, hard seed on a weathered, calloused hand for inspection. After uttering a quiet grunt of satisfaction, Smith goes about the process of preparing a row and planting this year’s squash crop next to some corn and sunflowers. It’s going to be a good year.

We have grown a smaller variety of Hubbard squash called Sibley at the Genuine Faux Farm, though we have favored butternut and buttercup types for our farm’s production over the years. Our goals aren’t the same as Asa Smith’s, who was probably looking for food production that could store over a long winter.

Even Gregory admits in his own catalog (1871) that his Hubbard squash perform differently in different areas of the country. Any good horticulturist or seed producer is going to recognize that one piece of land will perform differently from the next with any given variety vegetable. We have learned that Hubbard squash are not as fond of our farm as other types. Yes, we can grow them. No, they’re not the best choice at the Genuine Faux Farm.

Some Hubbard varieties can easily reach 30 to 40 pounds in weight and they sport an extremely tough shell. These squash are known to store well for a very long period of time. In fact, they typically taste better if you allow them to store for months before eating them.

And now, I am afraid I must conclude this week’s edition.

I’ve got some squash to plant.

Well we’ve done it, once again! Another Postal History Sunday in the books! Thank you for joining me. Have a great remainder of your day and a fine week to come.

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack. And, some publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest.

From damaged Air Mail to Squash today! Thanks Rob. Have a safe, thoughtful, and happy Memorial Day.

I was interested in the aircraft used on the stamp. A little research indicates that these "twin-engine transport plane" stamps used an artist's concept of a transport plane, with characteristics of several aircraft of the day, like the DC-3 but also the Lockheed Electra and Beech 18. (https://aviation.stackexchange.com/questions/33891/which-aircraft-is-depicted-on-1941-u-s-post-office-airmail-stamps)