I’ve mentioned the concept of a treasure hunt in the postal history hobby before. In fact, it was a theme for PHS #232, Dutch Treat, that was posted in January. This week, I’ve got another treasure hunt item to share with you!

In general, the concept of relative scarcity is simple. For example, in the game of baseball about 75% of pitches a batter swings at result in contact. about 40% are foul balls and and 35% are put “in play.” Of the balls in play, most result in an out. The next most likely result is a single, where the runner only gets to first base safely. Meanwhile, only 2% of all safe hits are triples.

In other words, you are unlikely to see a triple in that Major League Baseball game you plan to attend later this season. So, if you do see one, you can mark off a difficult square on your treasure hunt.

And now that I’ve gotten the analogy for the day written, it’s time for Postal History Sunday!

A rare 24-cent 1861 cover to Denmark

If a triple is an uncommon occurrence in a baseball game, this cover may be the equivalent of an inside-the-park home run, which would be rarer than a triple. This is the only recorded example of a cover bearing the 24-cent 1861 stamp that has a Denmark destination. And, like the cover to the Netherlands in Dutch Treat, it certainly makes sense that these would be very hard to find.

The Danish destination aside, this is an interesting puzzle cover that is worth breaking down. So, I thought I’d start with that! I’m going to try to “read” the cover in a way that brings you along for the ride.

Don’t worry, there isn’t a quiz at the end. Just sit back and relax.

This letter was mailed in Boston at some point from May 16 to May 18 in 1866. The exchange marking at the left has a date of May 18, but the US foreign exchange offices used these to indicate ship departure dates, not the date of arrival at the post office. The most recent previous trans-Atlantic sailing had departed on May 16, so if this letter had been mailed prior to that it most certainly would have departed on that sailing from New York (Wednesday on the Cunard Line). The May 18 date was an indication that they intended to send the letter to Quebec so it could cross using the services of the Allan Line (you can read about them in PHS #250 if you would like).

Postal markings are applied, in part, as messages to the mail clerks that handled letters as they traveled towards their destination. One critical piece of information in the 1860s was whether or not a letter was prepaid or if some or all of the postage would need to be collected when the letter was delivered.

The Boston exchange marking was applied in black ink - a message that told clerks down the line that the letter was not fully paid, even though there was 24-cents paid by the postage stamp on the envelope. The “6” indicated that the US Postal Office expected the equivalent of 6 cents to be sent back as the amount due to them when the postage was collected from the recipient.

In addition to the black exchange marking, the Boston Foreign Mail Office also added a marking that read “Short Paid.” This was meant to explain that the postage was recognized, but they had determined it to be insufficient to get the letter to Denmark. At the time, most short paid foreign letters were to be treated as completely unpaid. The 24 cent stamp would become, in essence, a donation to the US Post Office.

Either the clerk that initially processed this letter or their supervisor realized that there actually was an option that would allow this letter to be fully prepaid. So, they used a blue pencil to cross off the “Short Paid” and the “6” on the Boston exchange marking.

Then, they sent the letter to the New York Foreign Mail Office.

The New York office applied their own exchange postmark in red ink, indicating that the letter was fully paid. The date of anticipated ship departure was January 19, a Saturday. This letter was intended to be carried on a North German Lloyd steamship to Bremen, a free Hanseatic City (German). NGL’s steamship New York successfully crossed the Atlantic and arrived in Bremen on June 2 after a brief stop at Southampton (England) on May 31st.

In addition to the read circular marking, the New York office also impressed the number “17” in red ink on this cover. This indicated to the clerks in the Bremen postal system that 17 cents were being passed to them to cover their share of the expenses. This included 6 cents for the Atlantic crossing, 1 cent for Bremen’s internal mail, 5 cents for the letter to be carried to the border of the German-Austrian Postal Union (GAPU) and 5 cents to be given to the Danes for their portion of the postage.

The US was set to hold onto 3 cents for their postage, based on the postal convention with Bremen. But, because this letter was overpaid by four cents, they still got a donation, bringing their total to 7 cents.

Transit markings, which include exchange office markings, allow us to track the progress of a cover. The back of this envelope actually provides us with lots of information - as long as we can figure out what they say.

This is where I benefit from studying many other covers from the 1860s in Europe. I have actually seen each of these particular markings more than once, which means I can recognize them even if the current example is not very clean or clear.

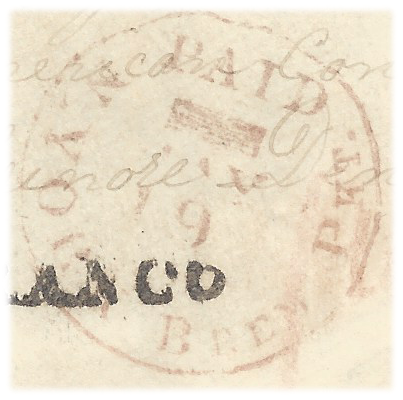

Shown above is a Bremen boxed marking that nicely matches up with the reported arrival date of the New York in Bremerhaven, Bremen’s port on the Weser River. A more typical exchange marking for Bremen is shown below:

This exchange marking in blue, “America uber Bremen Franco” makes a regular appearance on most covers that are exchanged with Bremen. Instead, the black boxed marking along with the word “Franco” on the front seems to have served the purpose this time.

The exchange office in Bremen recognized that this letter was fully paid and was communicating that fact with the word “Franco” (franked or paid). This may actually be the reason Bremen used different markings for this letter than they did for so many others. It is possible that Bremen had a postal agreement wtith Denmark that called for this combination of post marks.

It’s a theory that is worthy of further study because that’s the sort of thing I do. It is not, however, something that really makes a big difference when it comes to reading this cover.

So, let’s move forward by looking at the other transit markings on the back.

The letter traveled by rail to Lubeck (Luebeck), another Hanseatic Free City. The Lubeck Post initially received the letter on June 3, which is evidenced by the Luebeck marking at the right with the letters “St.P.A.” at the bottom (Stadt Post Amt - City Post Office). It was transferred to the Danish Post in Lubeck, which is shown by the blurry marking at the left that reads “KDOPA Lubeck 3/6” (Königliche Dänische Oberpostamt).

The letter finally reached its destination in Helsingor (Elsinore) on June 4. That postmark is weakly applied at the bottom right. You can see the “NG” of “Helsingor” clearly, but the rest is extrapolated by knowing that the letter was addressed to Elsinore and having other examples of that postmark to make comparisons.

If you’re keeping score at home, here’s a quick summary.

Mailed in Boston (May 16-18)

Boston exchange office marks it short paid and to go via Quebec

Boston changes their mind, sends it to New York

New York Foreign Mail Office marks it as paid and puts it in mailbag for May 19 (Saturday) departure

North German Lloyd’s steam ship New York crosses Atlantic Ocean arriving in Bremen June 2

Bremen recognizes letter as paid, sends it on to Lubeck

Lubeck City Post receives letter on June 3 and passes letter to Danish Post

The Danish Post Office in Lubeck takes charge of the letter on June 3

The letter arrives in Elsinore on June 4

Sidebar! - Lubeck post offices

This seems like a good moment to provide a sidebar.

The concept of a city or country hosting more than one postal service might be a little confusing, but it was not an uncommon occurrance. The Hanseatic Cities of Hamburg, Bremen and Lubeck actually hosted several postal services, including their own. At the time this letter was mailed, there were post offices for Thurn and Taxis, the Lubeck City Post and the Danish Post Office operating in the city.

For those who would like to learn more about post offices in Lubeck, I suggest this interesting handout by Chris King.

Choices, choices!

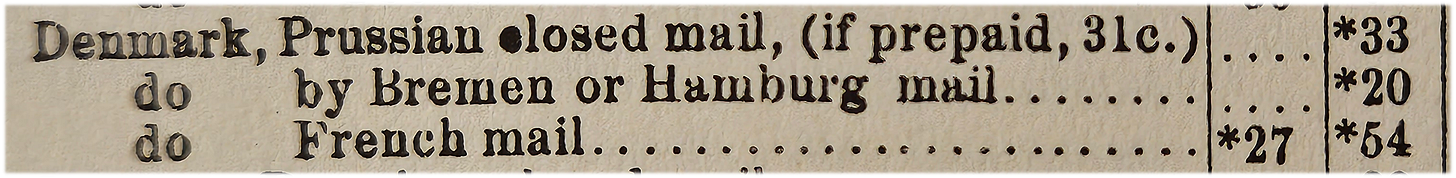

An individual wishing to mail a letter from the US to Denmark in May of 1866 actually had a few choices to make. They could opt to send the letter via Prussia, France, Bremen or Hamburg. And, they could send the letter fully paid or unpaid. They could not send letters that were partially paid.* Those were treated as fully unpaid.

The postage rates were different depending on the choice the sender made. They could send it via the Prussian Closed Mail for 31 cents per 1/2 ounce if it was prepaid, or the recipient could pay the equivalent of 33 cents in Denmark if it was sent unpaid. If they sent it via Bremen or Hamburg, the cost was 20 cents per 1/2 ounce. French Mail cost 27 cents per 1/4 ounce.

From a pure financial perspective, 20 cents per 1/2 ounce sounds like a pretty good deal, doesn’t it? So there must be a catch.

That catch was that mail via Bremen could only be taken on North German Lloyd ships and they sailed every two weeks from New York on Saturdays. Mail via Hamburg could only be taken on HAPAG Line ships and they sailed on Saturdays that alternated with the North German Lloyd. French and Prussian mail could be taken on any trans-Atlantic shipping line with a contract - including HAPAG and North German Lloyd.

It was cheaper, but it was also less convenient. But, since the postage rate via Hamburg and Bremen were the same, it wasn’t terribly inconvenient. A ship that could carry mail at this postage rate departed once a week.

*note: there was an option that was not advertised for Denmark, but may still have been used. The “open mail” provision with the British Post Office allowed for letters to be “paid only to England” and then sent unpaid from there to its destination. There are examples of this open mail being used even for European destinations where it was not listed.

The root(s) of the problem?

Now that you know the options for postage rates to Denmark in May of 1866, I suspect you could make a good guess as to what the sender of this letter intended when they put 24 cents on this letter. They most likely meant to cover the 20 cents per 1/2 ounce rate to Bremen or Hamburg. But they may have confused matters when they did not exactly pay the postage required.

You could say that a convenience overpay on their part led to identification issues in the Boston Foreign Mail Office.

But there was another factor that came into play as well. Boston was an exchange office for mail going to the British, French, Prussian and Belgian mail systems. They were NOT an exchange office for Hamburg and Bremen.

With an odd postage amount and no directional docket saying “via New York” or “per Bremen mail,” the clerk in Boston - potentially a less experienced clerk - was probably only looking at options that the Boston exchange office could fulfill. That left them with Prussian or French mail and 24 cents was not enough to pay for either one of them.

That meant the letter had to be treated as unpaid.

We are able to determine that the clerk’s decision was to send it via French Mail simply because of the debit amount on the Boston exchange mark. If they had selected Prussian Closed Mail, the debit amount would have been 23 cents. Possible debit amounts for French Mail would have been 3, 6, 12, or 24 depending on the contract the shipping country held AND on whether this letter weighed less than 1/4 ounce or more than 1/4 ounce and less than 1/2 ounce.

The “6” on the Boston marking along with knowledge that the May 18 date indicated carriage from Quebec on the Allan Line tells us the letter must have weighed more than 1/4 ounce (a double weight letter). While the Allan Line had a contract with the US to carry US mail, letters to or via France were to be treated as if the Allan Line had a British contract.

Happily for the sender and the recipient, a correction was made in Boston and the letter was sent to New York, where they could process mail for Bremen.

What makes this an inside-the-park homerun?

There are many factors that create the relative scarcity of an 1860s letter from the US to Denmark bearing a 24-cent stamp.

The number of letters sent to Denmark was much lower than many European nations.

The destinations with the most mail volume were typically countries that had mail conventions with the US, like the United Kingdom, France and Prussia. Higher volumes of mail encouraged agreements that made it easier to get mail between countries. The relative paucity of letters to Denmark is a reflection of limited direct business interactions and lower immigration numbers. The numbers of people coming to the US from Denmark started to rise after 1864 and hit its peak in 1882 when over 11,000 Danes entered the US.

The Bremen and Hamburg rates (20 cents per 1/2 ounce) were, actually, the most attractive rate to use. A 24-cent stamp wasn’t needed to pay that postage.

Since a ship departed for Hamburg or Bremen every Saturday, the delay in the mail was not so considerable that people would be terribly tempted to use the MUCH more expensive options via French and Prussian mail. Even a very light letter (less than 1/4 ounce) was more expensive via French Mail. Most existing pieces of mail to Denmark during this period show lower denomination stamps to cover the 20 cent postage rate. So, if letters to Denmark were uncommon in the first place, it becomes much more difficult to find one with a 24-cent postage stamp.

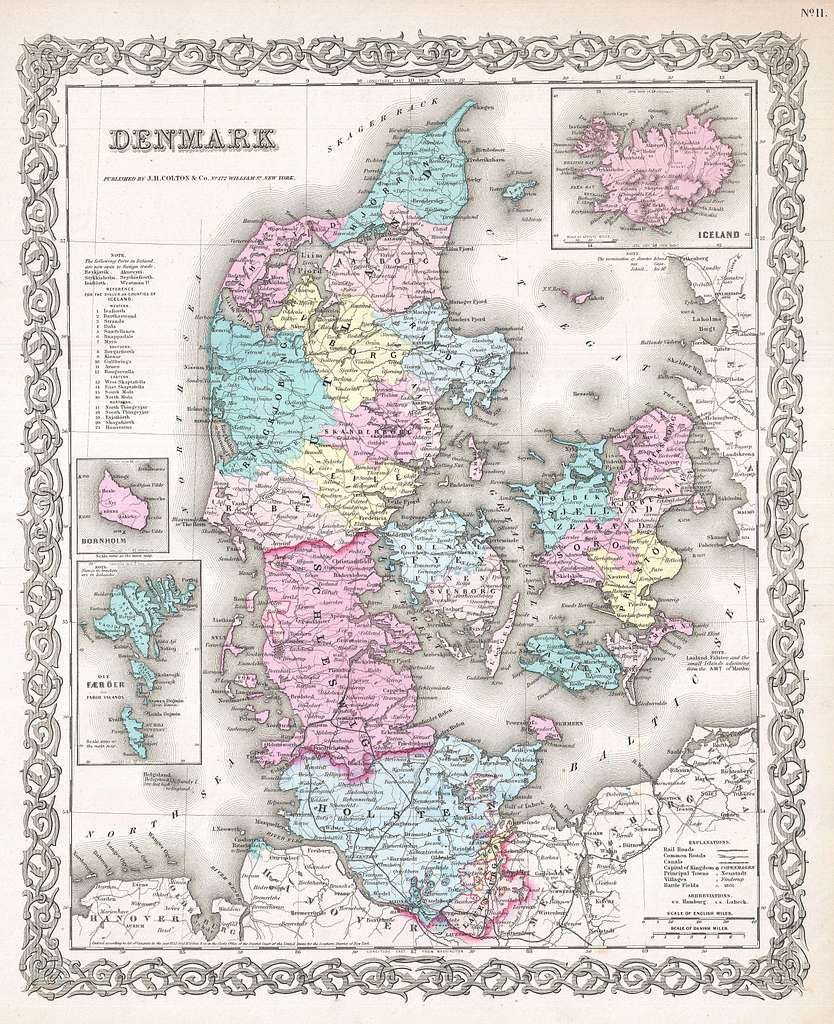

Denmark’s territory had been reduced in 1864.

After the Dano-Prussian War of 1864, Denmark lost over 1/3 of it’s territory, ceding the territories of Schleswig, Holstein and Lauenberg. Letters to Denmark were already less common than other destinations. They become even harder to find if you reduce the size of the country.

Of course, the volume of mail to Denmark went up as immigration numbers increased. But, mail volume to all destinations from the US was, generally speaking, increasing from the 1850s to the turn of the century. At the same time, postage rates were declining and the 24-cent stamp became less useful for mail to European destinations starting in 1868.

If other covers to Denmark with a 24-cent 1861 design stamp exist, they are likely either overpays of the Bremen/Hamburg rate (like this one), they were sent via one of the less attractive postage rates (France or Prussia) or they were used to pay for a heavier letter. None of these factors do much to increase the likelihood that we could find other 24-cent covers to Denmark.

Could they exist? Of course they could! But I’ve been looking for awhile and haven’t found one yet.

Another sidebar - What’s this?

There is another pencil marking, in red, that might give us a bit more information if it was applied by a postal clerk. It is located near the New York exchange marking. This could have been applied in Boston, New York, Bremen, Lubeck or Elsinore - until I get a better idea of what it says, I’m not getting attached to any of these options.

This could be a weiterfranco - a marking indicating an amount of postage to be passed forward. Probably passed to Denmark. Or it could be an explanation or direction for correcting the improper routing in Boston. Or maybe, it’s just another marking indicating the letter is paid.

If you have thoughts, feel free to share them with me.

Thank you for joining me. I hope you enjoyed this edition of Postal History Sunday. Have a great remainder of your day and a fine week to come.

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack.

That Denmark map is a beauty! Another great Sunday post! Gives me a lot of respect for the postal clerks that had to try to figure all of this out, while keeping the various postal agreements in mind.

Very interesting read with my morning coffee!