Welcome to Postal History Sunday! This is the place where I share my enjoyment of postal history in a way that is accessible to people with anything from a passing level of interest to expertise in the subject. My hope is that each person who takes the time to read these articles walks away with some new bit of learning or is able to relax and be entertained by what they find here.

Postal History Sunday is now approaching 300 subscribers (yay!), which tells me there are a number of people who might like a general introduction. This project started in August 2020 during the pandemic. In February of 2024, I moved to the Substack platform in an effort to make it easier for interested people to access these writings. At this point in time, I can tell you it has been a successful process - mostly.

There are still some issues with the editing tools (it might be me or it might be the tools) and there is always the issue of finding the time to do “administrative work” in addition to the writing. And, of course, there is the ever-present issue with emails going to people’s spam folders. It doesn’t seem to happen often, but it does occur! Postal History Sunday is released at 5 AM Central US time on Sunday every week. So, if you don’t see it, check that spam folder!

If you are looking for a broader introduction, let me suggest the About page for Postal History Sunday. And, if you want more knowledge about me, you can go to the About page for the Genuine Faux Farm. I am still maintaining a separate blog there and I invite you to subscribe to it if you have interest (there is a button at the end of the GFF About page).

Finally, I typically include a button at the end of each post to make it easy for you to share Postal History Sunday with others. Feel free to use that button if you know someone, postal historian or not, that might enjoy these writings.

And now, let’s put on those fuzzy slippers and move on to Postal History Sunday!

Getting a lot of mileage out of a Doanwanna

I’d like to start by sharing a pleasant surprise we received in the mail not long after PHS #218 (The Case of the Doanwanna). Mick and Vicky Hadley were very kind to send this package my way - complete with some effort to replicate the original item I featured in that article. Of course, the 9 cents in postage shown here was not sufficient to send the package my way in 2024, so there is a postage label on the bottom of the box that covers the bulk of the amount required to send this box via the US Postal Service.

The great thing about this box is that it is very close to the same size as the item I featured AND it has a printed portion on the box that says it was made at Attleboro Falls - where the Mason Box Company was located. In fact, Mason still offers a line of Mailmaster boxes very similar to this one. So, if you wanted to start mailing smaller fun items to your friends and family, you can get boxes like these and use them for that potentially enjoyable project!

The bottom of the box I featured in the Doanwanna article was no longer with the top, so I could not show you how the fastening technology worked. The absence of the bottom was really not a shock to me because most postal history collectors prefer to display flat items. They take up less space and they can be mounted onto a page with information and descriptions that highlight some of the interesting features. And, frankly, the bottom wasn’t necessary for the postal history part of the story.

But, in case you haven’t noticed - I don’t usually stop at the basic postal history facts - at least not where Postal History Sunday is concerned.

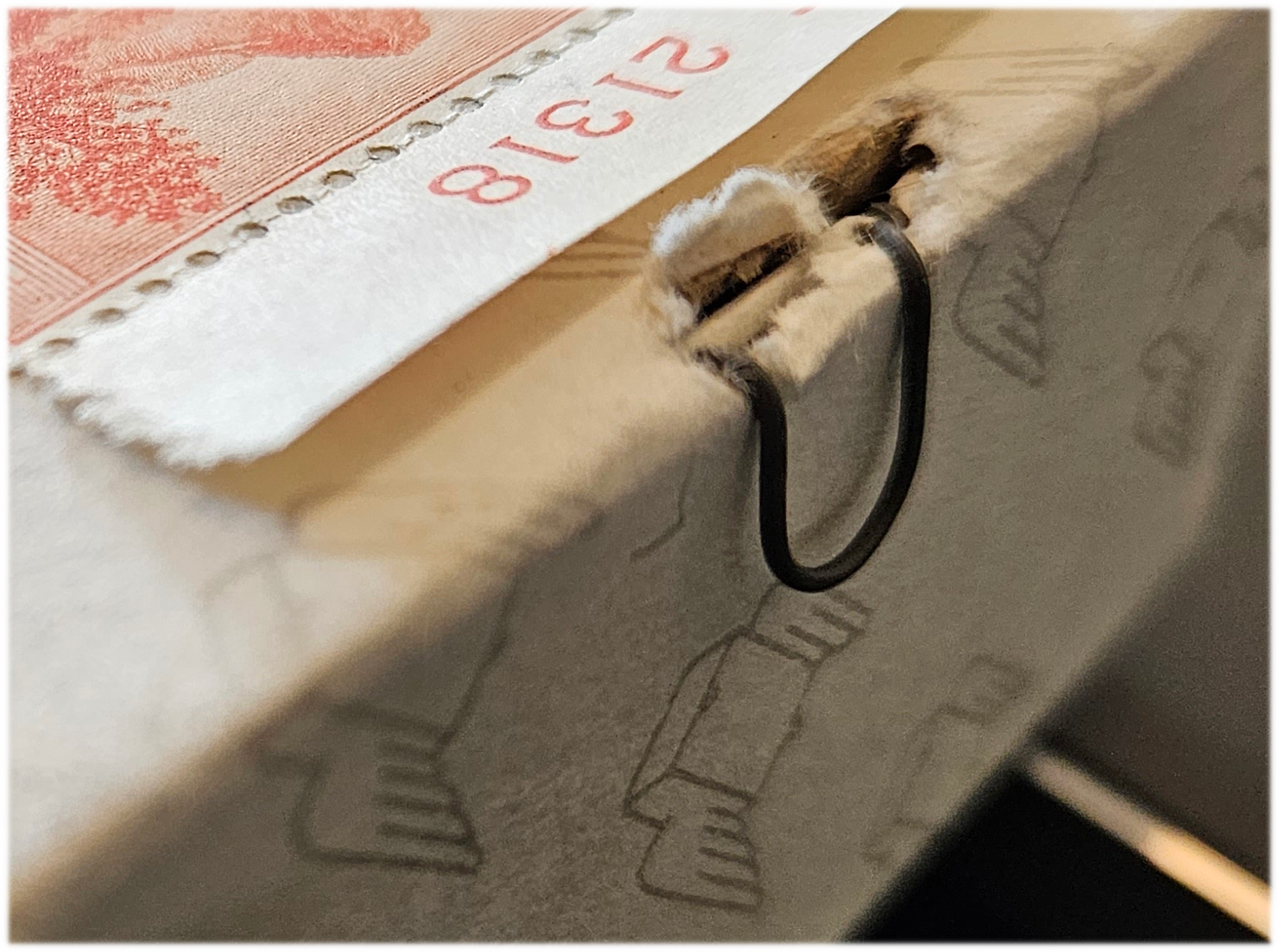

Now that I have a working example of the fastener technology, I can show an image of the metal wire that pushes through the slit on the top of the box and is bent over to hold the lid in place. It’s actually a very clever bit of work that was patented in 1926 and is still being used in some of the Mailmaster boxes being sold today!

In the present day, I suspect there is some sort of automation that pushes the wire through the box and bends it into shape. But, in 1926, these fasteners were attached to the box by hand. The patent application discusses how the wire is inserted into two holes and then bent around to hold it in place. So, I would not be surprised if numerous people were hired to put these fasteners on boxes for hours on end.

For their sanity’s sake, I hope they didn’t have the same task every day at the Mason Box Company. Unfortunately, assembly line technology typically did make people do the same repetitive task day after day. So, my hope is likely going to be dashed. I suspect it could be a bit like hand weeding crops on our farm, without the benefit of hearing the birds singing in the background.

The Last Leg of a Merry Chase!

It never fails, I publish an article and then I learn more about the things I show there. Eventually, the weight of those “missed opportunities” gets too heavy and I feel the need to share at least some of those additional tidbits. This next section focuses on this 1862 letter sent from Clyde, New York to Madeira Island - then under Portuguese administration. I featured this cover in PHS #215 (A Rate Puzzle and a Merry Chase).

Initially mailed UNPAID at the Clyde post office, the letter was sent to the foreign mail exchange office in New York City where the clerks were unhappy with the lack of payment. They expressed their disappointment with a “Returned for Postage” marking and sent it back to Clyde - where it took a few days for the sender to come in and provide payment.

Once the 29 cents in postage was paid, the letter was sent again from Clyde to New York City. This time, the foreign mail clerks were willing to send it on its trans-Atlantic voyage to England and then France. While in France, it was determined it was too late for the letter to take the ship from Lisbon (Portugal) to Madeira, so it went back to London and then Liverpool.

It was at this point that I waved my hands in what I hope was an impressively mystical or magical fashion and told everyone that the letter took a ship from Liverpool, probably departing on the 24th of August, to go to Madeira.

Well, now I have evidence that helps fill in the story and no further hand waving is needed.

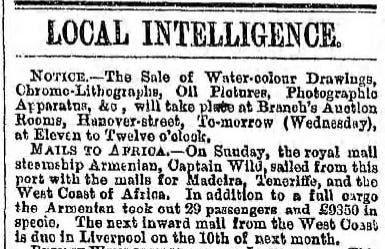

Newspapers during this time period - especially those in major port cities - regularly published “shipping intelligence” that reported the arrivals, departures and (sometimes) progress of various water vessels. Ships carrying the mails were often of particular note. The clipping shown above tells us that the Armenian (of the African Steam Ship Company), with Captain Wild in charge, sailed from Liverpool on the 24th (Sunday) for Madeira, Teneriffe, and the West Coast of Africa. Given the London postal marking dated August 23 and the knowledge that mails for Africa left Liverpool each month on the 24th, I can be fairly certain when I say this letter was on that ship.

After more searching, I found a travel book by Sir Richard Francis Burton titled Wanderings in West Africa from Liverpool to Fenando Po. And, after more digging, I am convinced that he was writing about this particular voyage of the Armenian. That means we can now get a more detailed look at the travels this particular letter took as it found its way to the addressee.

Burton obscures the details of his travels by using pseudonyms or giving partial information, but he leaves several clues that allow a persistent individual to work things out. The title page on the book lists the author anonymously as “A F.R.G.S,” which translates to “a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society.” And, since Burton clearly enjoys his clever wordplay, he named the ship Blackland under the command of Captain English - referencing the African continent and the English shipping company that was carrying him there.

The Blackland departed Liverpool on August 24, 186_, with Burton intentionally leaving out the last digit of the year date. But, in the forward for the book, he gives a date of December 1862 in West Africa. Along with a few other clues, I think it is highly likely that his writings document the voyage this letter took to Madeira. However, even if this isn’t true, Burton does give descriptions about how mail was carried by the African Steam Ship Company to Madeira and the West Coast of Africa that would still apply.

In addition to describing the loading of 35 mail bags in Liverpool that would cover ALL of the destinations on the Armenian’s route, Burton’s account also tells us that a steamer named Lusitania sailed between Lisbon and Madeira on a monthly basis. Between ships sailing from Liverpool on the 24th of each month and the Lusitania leaving Lisbon on the 10th (or somewhere near that), Madeira received mail from Europe twice a month.

This provides me with an explanation for one part of the Merry Chase this letter took. This letter was on its way to Lisbon, but the Paris postal clerks turned it around and sent it back to England. The Paris post office knew it would be quicker to send the letter via London and Liverpool because the next scheduled sailing of the Lusitania was probably September 10, which would have delayed this letter further.

With this new routing, the letter actually made it to Madeira on August 30. Upon arrival at the Bay of Funchal, the ship (according to Burton’s account) fired its guns to announce its arrival - attempting to get the attention of the “health officer” who needed to inspect the ship before passengers were brought to land. There were still erratically enforced quarantine restrictions at Madeira due to the “1956 cholera year” and this visit was required once the ship had anchored.

The single bag of mail destined for the post office in Funchal, on the other hand, was taken almost immediately to shore. As Burton puts it “[t]he commander of the H.M.S. Griffon, after vainly awaiting permission to board us, at last lost patience, and carried off his mailbag.” And it seems likely this letter was in that bag.

Now I can offer a more complete summary of the Merry Chase this cover went on:

Clyde, New York - July 19, 1862

New York City Foreign Mail Office - probably July 19 or 20

Clyde, New York - probably July 21 or 22 until August 6

Clyde, New York - August 6 - postage paid

New York City Foreign Mail Office - August 6 or 7

HAPAG’s Saxonia - August 7 - August 21

Southampton, England - August 21

Train from Calais, France to Paris - August 22

Paris - August 22 *Too late for August 10 departure of mail from Portugal and faster to go to Liverpool vs waiting until September 10 for the next trip from Lisbon*

Train from Paris to Calais - August 23

London - August 23

Liverpool - August 23 or 24

African Steamship Line Armenian - Departing afternoon of August 24

Arrival at Funchal, Madeira - late on August 30, mails taken by HMS Griffon, passengers disembark next day.

Hot Crossing Topics

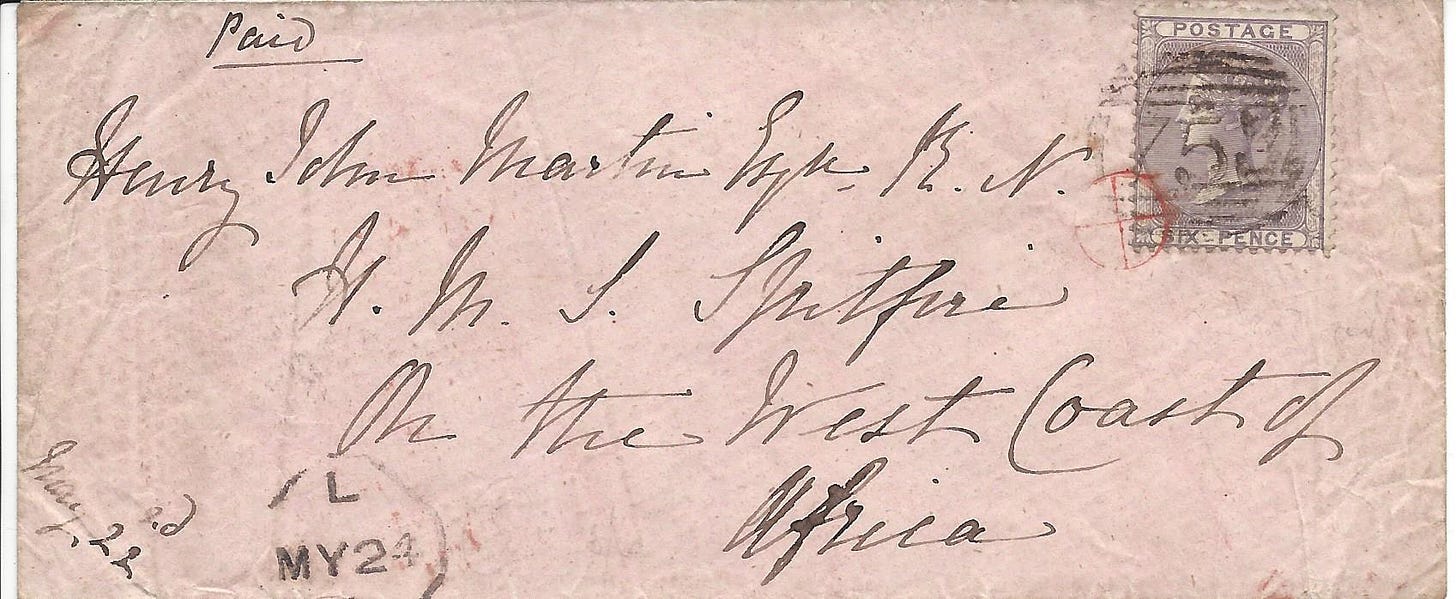

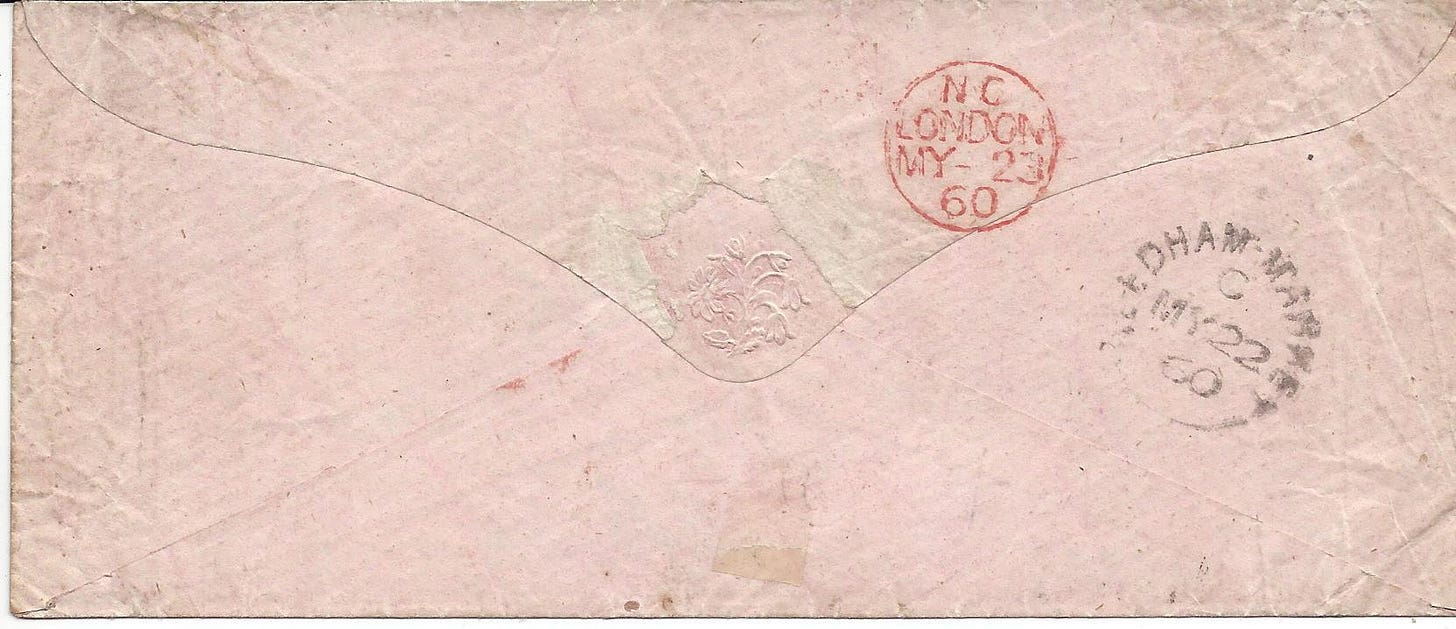

This next item actually spans two recent topics and serves as an excellent bridge from one to another. This letter was sent from England (Needham Market on May 22, 1860) to Henry John Martin on the HMS Spitfire.

The address? “On the West Coast of Africa”

Well, that’s um… helpful? But let’s make our topic connections first, shall we?

We were just talking about a letter sent to Madeira - which was, at the time, on the way to the West Coast of Africa as far as mail travel was concerned. And, sure enough, if you look at the bottom left of this second cover you will see a postmark that says “L MY24,” which stands for Liverpool, May 24. That just happens to be the day each month an African Steam Ship Company ship departed on its way to Madeira, Teneriffe and the West Coast of Africa.

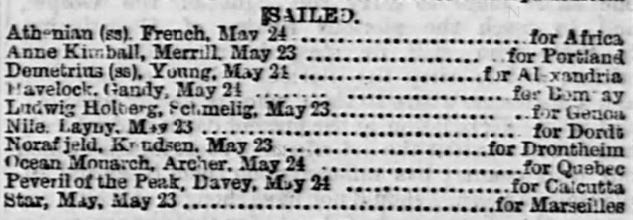

The Athenian, with Captain French in charge, sailed on May 24 for Africa, according to the newspaper clipping shown above. But the real question of the day is WHERE on the West Coast of Africa was this letter going to get dropped off? I mean… it’s not like there isn’t a fair amount of territory to cover when we’re talking about the West Coast of Africa is there (about 6000 km of shoreline)?

The details will be a task for another day because I need to save something for later! But I can say that I found shipping intelligence from the May 14th Liverpool Daily Post that the Spitfire had departed from Fernando Po to Lagos. We just need to consider that the number of locations a ship like the Spitfire would go were limited to ports like Funchal (Madeira), Teneriffe (Canary Islands), Fernando Po (island off Cameroon) and Lagos (Nigeria). So, it was not as if they would have to stop at every seaside settlement along the way to check if the Spitfire was waiting around for mail.

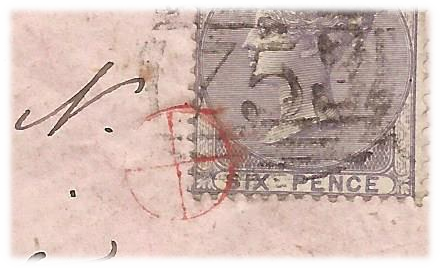

As for the link to another topic, it has something to do with the red marking that was applied at the bottom left corner of the postage stamp. This connects to PHS #212 (A Hot-Crossed Merry Chase) and shows a different sort of “hot-crossed bun” marking that was applied by the British Post Office. This one does not have letters imprinted inside of the wedges and is quite a bit smaller in size.

I have two possible explanations for this marking. One idea is that this letter was inspected to be sure it was properly rated at the foreign mail office. That might mean that they were checking the weight of the letter or looking to see if the correct rate for the selected route had been been paid for with the postage (6 pence). However, the envelope is so small and light, I doubt they were worried that it weighed too much.

The other idea comes from a book on British postmarks by John Hendy. Hendy’s work suggests that the marking tells us that this letter was sorted incorrectly, which delayed its processing.

I believe the hot-crossed bun marking was applied in London, which is supported by the May 23 marking on the back of this envelope that appears to have the same red ink. Thanks to information from Colin Hanson, who provided help about a year ago with related questions, we can refer to this London Late Fee and Too Late Mail resource for additional help. On page 66, a marking, like this circular London marking on the back of this cover, is described as being applied “on evening mail cancelled at the Chief (London) Office with single (i.e. undated) cancellations.”

This lends some credence to the idea that this letter was sorted incorrectly. Needham Market is located north and east of London and their dated postmark was placed on the back of the envelope - not the front - making it look like a “single (undated) cancellation.” It seems odd to me that a letter from Needham Market would receive an evening mail marking in London for the next day UNLESS the letter had been put in the wrong place. It should have been sorted with foreign mail and had no reason to be with the evening mail in London unless it was mis-sorted.

So, I will go with Hendy’s explanation for this cover - unless someone can convince me otherwise.

But, I still like the other explanation for this next letter, featured in this PHS. The contents of the letter are dated November 17 and the London postmark on the back is the same day. That makes it unlikely that anyone felt a need to mark it as being delayed due to mis-sorting. On the other hand, this letter is heavier than many folded letters that would qualify for the simple letter rate (no more than 1/2 ounce in weight). So, it makes perfect sense that it would have been checked to be certain that it met the requirements for the 1 shilling postage rate.

Post-publication Discoveries

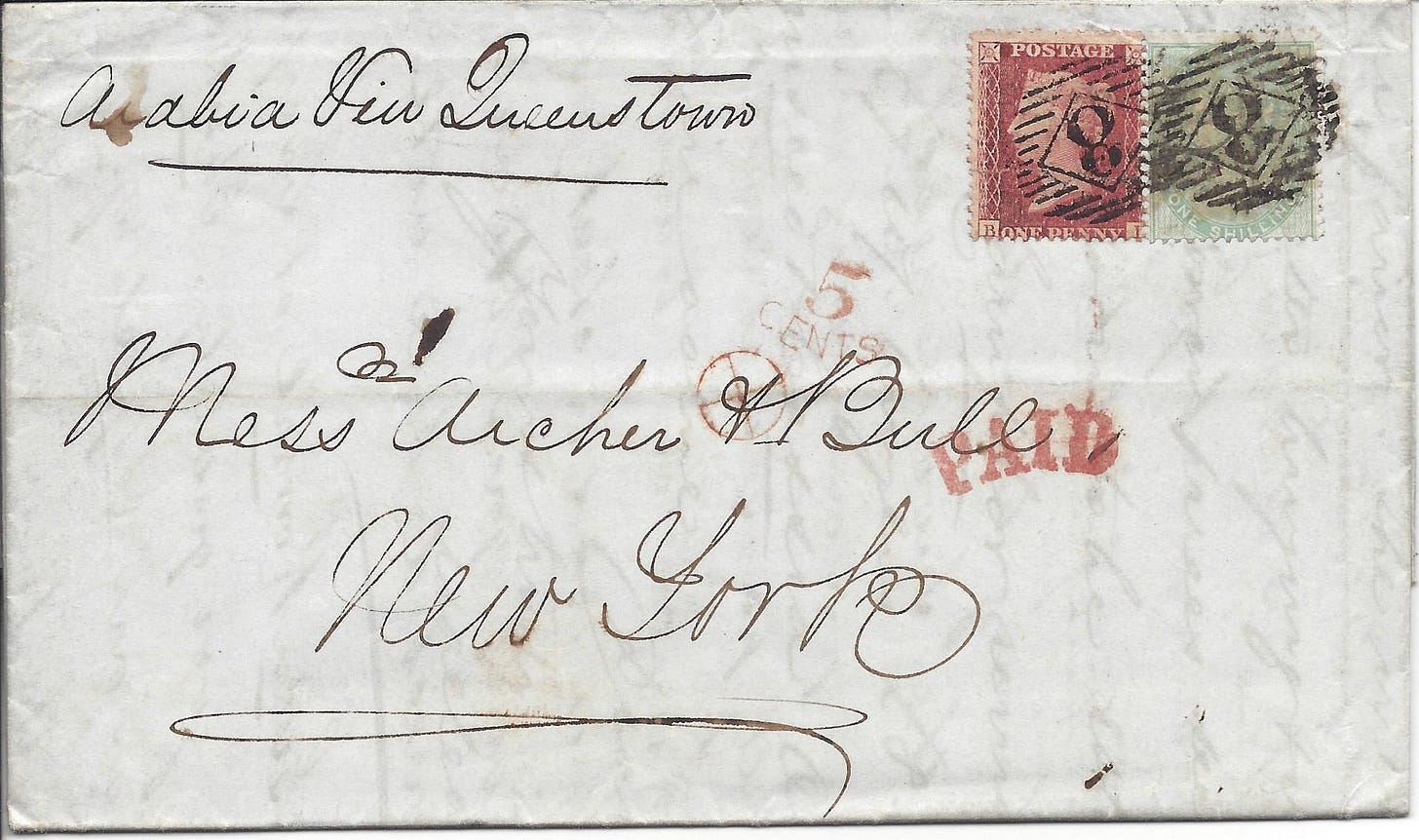

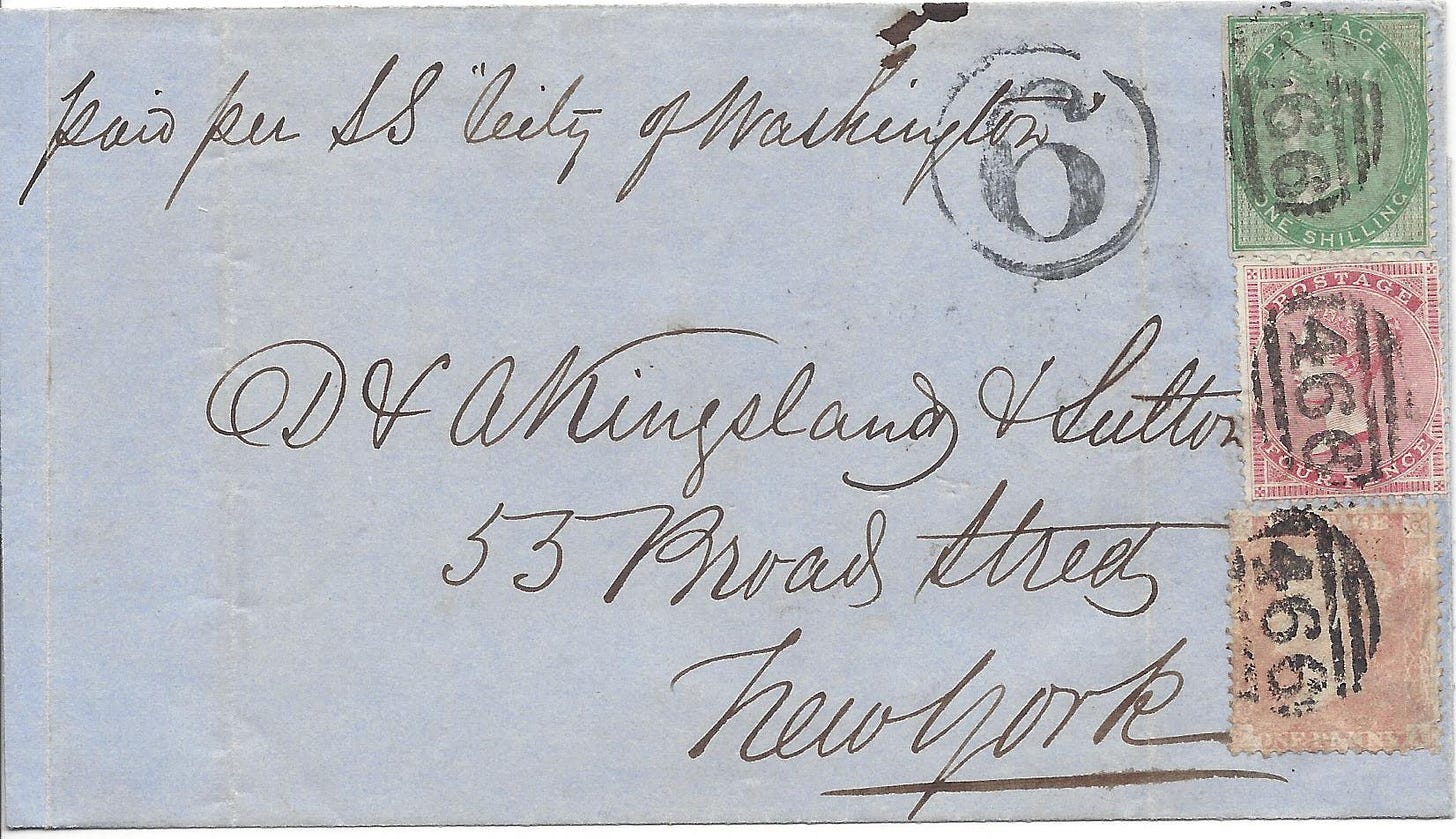

I’d like to close with an example of an item that might encourage me to rewrite a recent article at some point in the future. This cover was mailed in 1857 as a ship letter, rather than as a fully prepaid letter to the destination. In other words, the letter was prepaid to the port of entry, but the local mail costs would have to be paid by the recipient.

The cost for a ship letter from the United Kingdom at the time was 8 pence per 1/2 ounce and the 1 shilling and 4 pence stamps paid for a double weight ship letter to get to the harbor in New York. The recipient was responsible for the flat-rate fee of six cents as long as it was addressed to the port of arrival - which this was.

This is another fine “exception to the rule” for mail sent from the United Kingdom to the US in the 1850s and 60s. I covered several items in PHS #217 on this topic, but this one didn’t make the cut. But, I am beginning to think the article might be better if I included it - and one other example - in some future edition of Postal History Sunday.

Now, don’t you worry! The process of re-writing is such that you won’t see it again for a couple of years at the earliest. I’ve learned to take my post-publication discoveries and thoughts in stride. And when those things percolate long enough and I feel like I’ve reached a point of comfort that I have discovered enough, I will often produce a new version of that article - just like the recent effort for PHS #219 (Friends in Need).

I often feel that these second (or sometimes third) efforts produce some of the very best Postal History Sundays. And that’s a good enough reason to welcome these post-publication discoveries and allow them to sit around in my brain for a while.

Who knows where that might lead?

Thank you for joining me today. Have a fine remainder of your day and an excellent week to come.

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack. And, some publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest.

Cool!