Sprouting Wings

Postal History Sunday #231

One of the benefits of studying and writing about postal history (and the history that surrounds postal history artifacts) is that it provides me with an opportunity to gain a healthy perspective for the present. For example, letter mail between the United States and Europe in the 1860s crossed the Atlantic Ocean on relatively new steamship technology. But, even with that improvement, a response to a letter might not arrive for three weeks - even if the recipient wrote and mailed their answer immediately.

The 1860s featured the US Civil War and the ensuing Reconstruction Period and saw both Germany and Italy unify what were numerous semi-autonomous or autonomous states. Telegraph systems were becoming much more common and rail transport rapidly expanded.

All in all, a very interesting time that was packed with change.

This week, I’m going to move the target to the 1930s and the midst of the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl. As the decade progressed, conditions would lead to the Second World War. It was also the decade where the Emergency Conservation Work Act (Civilian Conservation Corps) employed 3 million people to improve services, plant trees, implement erosion control, and work on other projects at the various National Parks. And, it was the period of time when air travel options were rapidly expanding.

So, hold on to your hats, we might be sprouting wings in this Postal History Sunday!

Let’s start with a neat Rate Puzzle

If you are wondering why I was making a connection to the US National Parks in the introduction, you might begin to understand that now. The strip of three 9-cent postage stamps at the left of today’s first cover features Zion National Park and is a part of the 1934 National Parks set. Each of the first four covers today will feature that particular stamp issue.

I favored the National Parks issue when I was a very young stamp collector and I continue to enjoy seeing them on covers to this day. As a matter of fact, you will find more than one Postal History Sunday that features covers with these stamps including PHS #222, #221, #218 and #188.

This particular letter was mailed in New York City on September 10, 1934 and was destined to Sutton Coldfield (Birmingham) in England. According to a postmark on the back of the envelope, it arrived at its destination on September 18 at 6 AM. Because the sender paid for the additional Express (Special Delivery) service, the letter would have been taken to the recipient soon thereafter - rather than waiting for the first scheduled delivery of the day.

So, based on the postmarks, the letter arrived about 7 1/2 days after it was processed by the New York City postal clerks.

The published closing time for mail to be sent on the North German Line’s Bremen was 8:30PM on the 10th, so this letter was there in plenty of time to be put on that ship, which departed just after midnight. This cover was then off-loaded at Cherbourg, France, on the 17th where it was taken by mail train to Paris.

How do I know that, you may ask? Well, I have two reasons. First, the blue label with the red typed print at top right reads Par Avion/By Air Mail, In Europe Only. So, I was expecting it to get on a plane. The question was… where?

That’s where this other marking on the back of the cover comes in:

Air Mail service between Paris and London was initially established in November of 1919. Ten years later, in April of 1929, night flights to carry mail from Paris to London were implemented. And, by 1934, there were five flights in each direction between Croyden (London) and Le Bourget (Paris) airfields that carried passengers and mail. Based on this postmark, we can conclude that this envelope took the 4:30 PM flight from Paris to London - arriving about ninety minutes later.

At this point, I don’t know if the letter took the internal Air Mail service from London to Birmingham or it took the mail train. If someone knows that answer, I would be happy to hear your thoughts.

The initial attraction I had to this cover - other than the Zion National Parks stamps - was the odd amount of postage. There is a total of 28 cents in prepaid postage for this cover which required a little bit of puzzling (my thanks to Don Tocher for notes on the cover sleeve that helped guide the research). I thought it would be nice to simply list the information for those who might enjoy knowing the answer:

US Surface Mail to Foreign Destination - 5 cents for a simple letter up to one ounce (Oct 1, 1907 - Oct 31, 1953)

European Air Mail Service - 3 cents per ½ oz (Jul 1, 1932 - Apr 27, 1939)

Expres Service/ Special Delivery Fee - 20 cents (Sep 15, 1926 - Oct 31, 1953)

Mixing Air Mail and Surface Mail

Our next cover, like our first cover, illustrates the use of Air Mail for a portion of the letter’s travels. Unlike the first item, this item used Air Mail in the United States and then surface mail for the rest of the trip.

There are eight cents in postage stamps and one of the these is the 4 cent (brown) denomination depicting Mesa Verde in the National Parks series. The United States had a special postage rate (8 cents per ounce: Nov 23, 1934 - Jun 20, 1938) for mail that would use US Air Mail to get to the port of departure for foreign mail. That postage rate covered both the air travel and the surface mail required to get to the destination.

The letter shown above was directed to Victoria, British Columbia, in an effort to catch the Empress of Japan. The closing time for mail in New York City to depart via Air Mail and get to that port was the next day (March 19) at 2:30 PM. So, it certainly seems possible that a letter departing from Merion Station (west of Philadelphia), could get there in time - whether it flew from Philadelphia to New York or not. Since it was directed to use Air Mail, I suspect it took the scheduled flight to New York.

But, a lot can happen between here and there. Perhaps the letter did not get to New York City in time to catch the plane carrying mail on US Air Mail Route 1 to San Francisco. I suspect that, if it hadn’t, the New York clerks would have at least crossed off the directive to Victoria.

My guess is that there was a delay for the AM 1 flight on March 19 or the scheduled flight to Seattle (AM 11) had an issue. I don’t know for certain what the the delay was, but once the letter reached San Francisco, the clerks there decided it was “Too Late” to get to Vancouver on time for the Empress of Japan.

This provides Rob, the postal historian, with a bit of a puzzle to work out. If this letter didn’t take the Empress of Japan from Victoria, what did it take?

The clues can actually be found in the New York Times for March 18, 1937. The newspaper published mail closing times for the Trans-Pacific mails. This included options for both US surface mail (at a cost of 5 cents for a simple letter up to one ounce) or US Air Mail (at 8 cents per ounce).

The Empress of Japan is clearly listed under Air Mail Connections, but we know we missed that ship. So, we need to look at later shipping connections that could get to Batavia, Java, Dutch East Indies (now Jakarta, Indonesia). There are actually three sailings shown that list the Dutch East Indies, but two are for Parcel Post and not letter mail. The only sailing that lists letter mail for that destination is the President Jefferson - so I selected that one for further consideration.

The SS President Jefferson was listed for departure in the Seattle Daily Times on March 27, which gives our letter plenty of time to be placed on that ship. But, even better, the ship was scheduled to reach the Philippines (Manila) by April 19. This makes the arrival date of April 24 (shown by a Batavia receiving postmark on the back of the cover) an excellent match for this sailing.

Now, before I go much further, let me encourage you to look carefully at the smokestack on the ship. What you will see there is a stylized dollar sign ($). While you might be tempted to think that this was a reflection of the cost of accommodations on this ship, it was actually the ship logo for vessels that sailed for the Dollar Steamship Company, initially founded by Robert Dollar. This shipping line followed a tradition of naming all of its ships after US presidents and signed a contract to carry US mails beginning in 1928.

Ah, Postal History Sunday, the place where odd little factoids have a way of just showing up and derailing the entire train of thought… perhaps leading us to flights of fancy.

Surface first, Air later

Our last cover was an example of a letter that took US Air Mail to get to a port city and then surface mail to get to its destination. This item reverses that. Mailed in 1936, this simple letter to Brussels, Belgium used surface mails until it got to Europe. At that point, it used Air Mail to get to its European destination.

Once again, there is a National Parks issue postage stamp, but this one commemorates Acadia National Park and has a 7 cent denomination. The total of eight cents in postage covered five cents for surface mail to a European destination from the US and three cents for European Air Mail. Since the letter originated in New York City, there was no reason to use the US Air Mail service. It was already at a port city with an exchange office for European mail.

The New York City postmark shows us that the letter was received at 3:30 PM on the 21st, well before the closing time posted (8 PM) for items taking the North German Lloyd’s Bremen across the Atlantic Ocean. The colorful docketing at the top tells us that the letter was intended to be carried all the way to Hamburg and then taken by Air Mail via Berlin to Brussels.

This time, there are no markings to help us determine, for certain, where this letter went. Directional dockets were often, but not always, followed. Since we don’t have any transit or receiving postmarks to help us, we can only assume that it took the route via Berlin.

However, if speed were of the essence, it would have made more sense for the letter to get off sooner at either Cherbourg (as our first item did) or Southampton. Since we have evidence that Paris applied postmarks for their airmail (at least to London), I’ll eliminate that route from contention - unless someone shows me I am wrong (of course). Either way, I’ll just have to be satisfied with not knowing for certain what European Air Mail route it took.

Air, Surface, Air

This next item used Air Mail service in both the US and in Europe. The postage is paid by the three Zion National Parks stamps and one two-cent Grand Canyon stamp - totaling 26 cents. That’s another odd amount, so let me just lay that one out for you!

US Air & Foreign Surface to Europe - 8 cents per oz (Nov 23, 1934 - Jun 20, 1938)

European Air Mail - 3 cents per ½ oz (Jul 1, 1932 - Apr 27, 1939)

Registered Mail Fee - 15 cents (Dec 1, 1925 - Jan 31, 1945)

The intent to use Air Mail in both locations is clearly given by the docket at the bottom of the envelope “By Air to US Exchange Office, By Air from London.”

And now, you might have a very logical question to ask - Why not use Air Mail to cross the Atlantic Ocean?

There were certainly Air Mail services that crossed great expanses of water, including Trans-Pacific services starting in 1935. But, interestingly enough, regular Trans-Atlantic Air Mail from the US to Europe would not start until May 20, 1939. At the time these letters were mailed, there really wasn’t an option to do more than select Air Mail service on one continent, the other, or both. You were stuck with a sailing ship to cross “the Pond.”

Air Mail routes in the United States are, for the most part, traceable in the 1930s thanks to the survival of US Postal Bulletins and US Postal Guides. I am grateful for the work performed by people such as Mike Ludeman and Don Heller (and probably others I am not immediately aware of) to make US Postal Guides and other documents accessible online. Hathi Trust currently provides services that allow people like me (and you) access to historical materials, like the Postal Guides. And the US Postal Bulletins Consortium provides a searchable database to find source documents applying to topics like Air Mail.

It is because of these resources that I can tell you this letter likely left Houston, Texas on September 21 around 7 PM on a Braniff Airlines plane covering Air Mail (AM) Route 15 to Dallas/Fort Worth. From there, it transferred to AM 9 at about 10 PM (also serviced by Braniff) to get to Chicago. Once in Chicago it took AM 1 to New York City.

The USPS also provides a link to some higher quality images of postal maps at this location, if you are interested in seeing the evolution of these routes over tiime.

I suspect a person could find similar documentation to learn about the Air Mail routes in Europe and I know there are many who study the intricacies of that subject. I, however, am not one of those people. So, I will move on to this week’s bonus material!

Bonus Material - How certain am I? Not very.

When I described this particular cover to you, I very simply stated that the “Too Late” marking shown was applied in San Francisco. I did this without showing you any supporting evidence. So, this is the part of Postal History Sunday where I reveal reasons for conjecture, even if they might be a bit flimsy. *

If you look at the Air Mail routing map, you might notice there was a route option to take a northern route towards the Pacific Northwest and Victoria. The alternative was to go by AM 1 to San Francisco and then northward from there. Since AM 1 was the oldest route with the most scheduled flights, it makes sense to presume that this would be the most likely route - but I have no further evidence to back that up other than this:

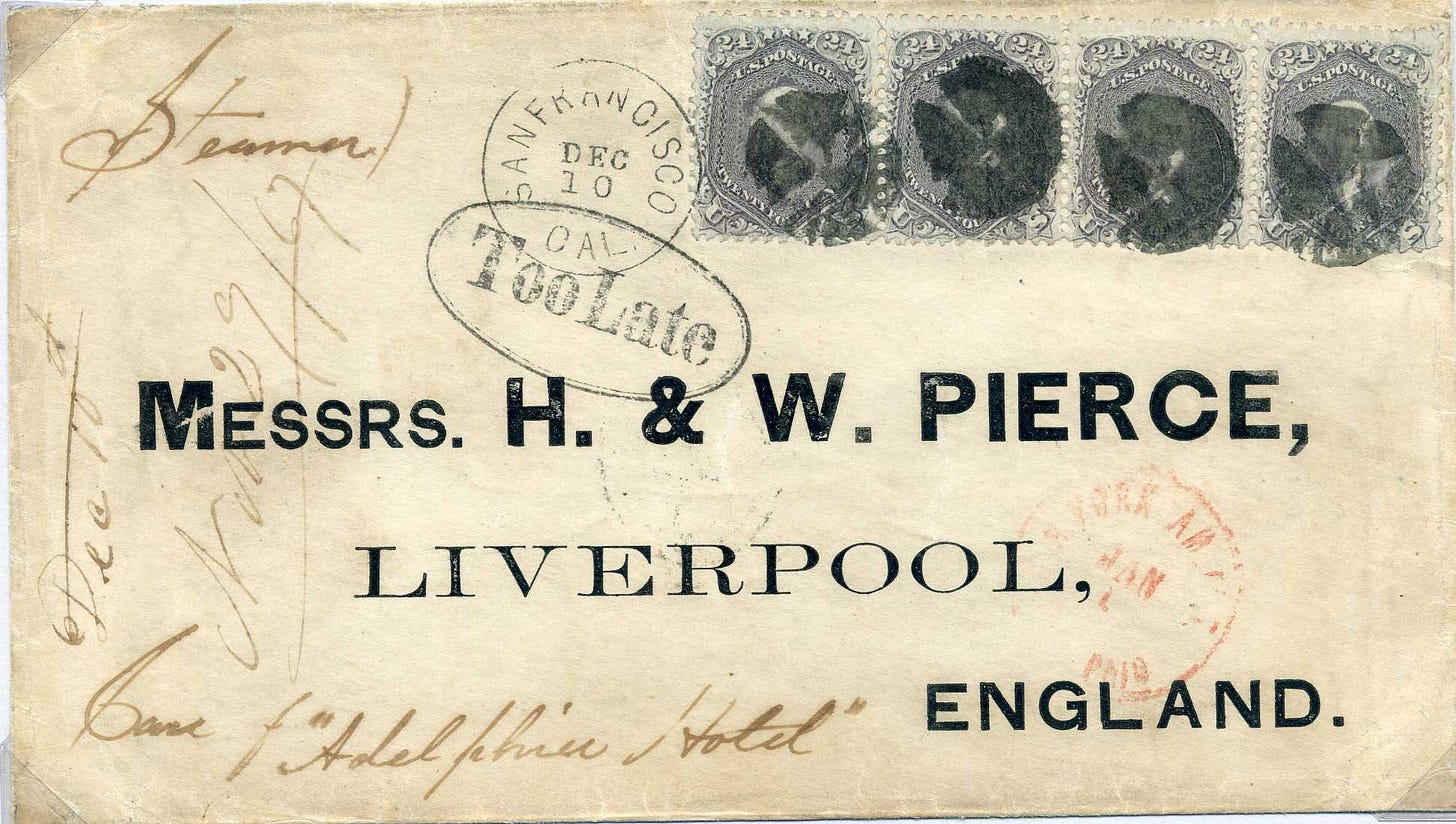

This is an 1867 letter mailed from San Francisco to Liverpool, England. It was received too late for the steamship departing on November 29, so it was held at the post office until the next steamer on December 10. The oval “Too Late” marking is a match for the one we find on this letter in 1937.

So, because I have record of this particular marking in San Francisco (even if it is 70 years prior) and that location makes sense for Air Mail routing, I came to the conclusions I did. Could I be wrong? Yes. And I am willing to entertain discussion on that topic. It’s certainly possible that Victoria or Seattle (or any number of other post offices) had a similar postmark. But, I do think my interpretations are plausible and hold together reasonably well. So, I’ll stick with it unless I (or you) discover contradictory evidence in the future.

It wouldn’t be the first time I’ve changed my mind on a postal history item and it won’t be the last.

*Typically, I prefer to be much more certain with conclusions. If I am not, I leave the conclusions out OR I do something like this. Explain my reasons and hope for more evidence from the crowd.

Bonus Material - Mail funding transportation expansion

Braniff Airways provided the air service for AM 9 and AM 15 at the point the letter to Greece was traveling from Texas to New York. However, AM 15 was originally provided by Long & Harman - which was purchased by Braniff in 1934.

As a postal historian who concentrates on the age of steam, I am aware of the vital role postal services played in providing funds for steamship companies during their early development. If it weren’t for the subsidies and contracts provided by governments to insure regular postal transportation by those ships, things would have been very different. It’s even possible that it would have suppressed or significantly delayed immigration that brought my own ancestors to the US by reducing shipping capacity.

Similarly, it was postal contracts that helped drive the development of air travel services in the US. Once Long and Harman secured a contract to carry the mail on route AM 15, they were able to court prospective passengers on those routes.

Wouldn’t you like to “Fly with the Air Mail?”

I will say that the seating appears to give a person a bit more space than the current coach class for the airlines I’ve been on. Maybe more than some first class services - though I wouldn’t know that from personal experience. On the other hand, I’m not sure I’m a fan of wicker seats and I am guessing seat belts and carry-on luggage space were not a thing then.

As long as they didn’t expect a person to hold a bag of mail in their lap, it was probably okay.

Bonus Material - Zion and the Civilian Conservation Corps

The purpose of the Emergency Conservation Act (Civilian Conservation Corps) was to provide work opportunities for young men during the Great Depression. I came across this CCC newsletter collection in the process of researching this week’s article and was amazed that so many CCC camps produced their own newsletters.

A portion of a newsletter for the Zion CCC camp is shown above and outlines four major projects in progress during April of 1937. These included road construction, river control, laying a 2-inch pipeline and building a ranger cabin.

I also managed to take note of a quick description of the name change from Emergency Conservation Act in the CCC Reflections newsletter for the CCC Camp at Bridgeland, Utah.

Of particular note is the change in requirements for a person to be eligible to be part of the CCC. Numerous newsletters, including this one, mention the need for more workers to complete the ambitious projects each camp was focused on.

Thank you again for joining me for Postal History Sunday! I hope you enjoyed today’s entry.

Have a great remainder of your day and a fine week to come.

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack. And, some publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest.

I inherited my grandfather’s stamp collection. He had eagerly collected the National Parks issue, including sheets and first day covers. It is a fascinating and storied issue, including the Farley’s Follies episode.

Another episode he collected involved the Admiral Byrd snafu…would love to read a column on that prolonged polar posting!