Writing Home to Family

Postal History Sunday #186

For those who enjoy these Postal History Sunday posts, I am perfectly happy to answer questions. In fact, I will often take those questions and queue them up as the topics for future. This one actually was prompted by a question - "Do you often get old covers that still have letters in them? What would a letter from the 1800s look like?"

A significant portion of surviving mail items from the 1800s, up until about the 1860s, was business correspondence. Most of the content for items from that period is likely to be some sort of receipt or business letter with very little of a personal nature. But, there are exceptions to that rule.

This entry will start with a fairly common business correspondence and follow with an item with personal content. So, put those troubles somewhere out of the way for a while and pour out a favorite beverage. Let’s put on those fuzzy slippers and get comfortable. It’s time for Postal History Sunday!

Business Content

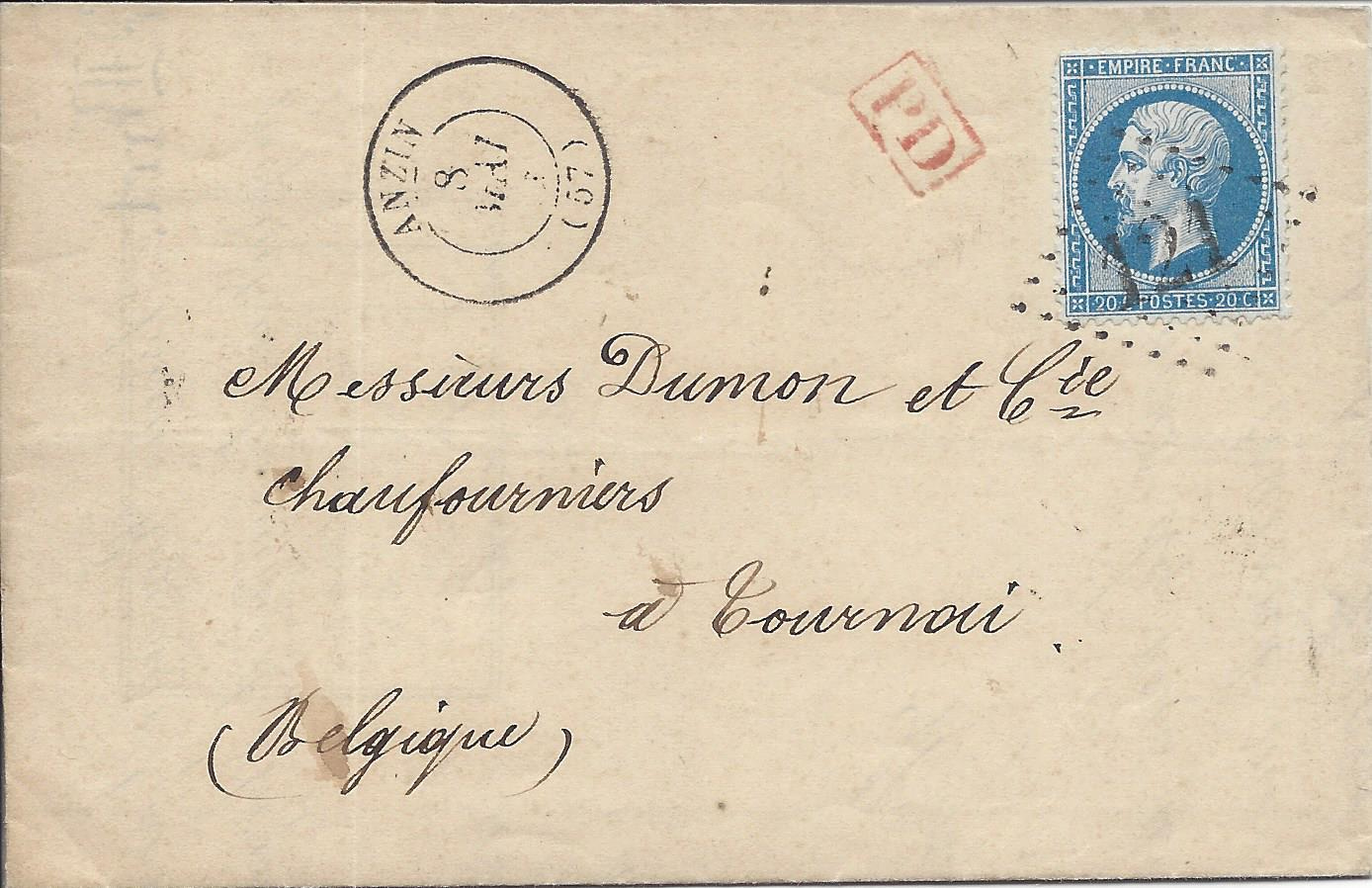

Shown above is a folded letter that was sent from Anzin (France) to Tournai (Belgium) in 1866. It is an excellent example of a postal history cover that was sent for the purporses of business and whose existence today may be, in large part, due to the need to keep such letters as business records.

From a pure postal history perspective, this simple letter is actually fairly interesting. At that time, there was a special postage rate between France and Belgium for letters being sent between border towns. So, instead of paying the normal 40 centimes for a simple letter sent from France to Belgium, this one only required 20 centimes - the same price an internal letter would have cost in France. If you would like to learn more about that topic, I suggest this entry.

The address tells us the recipient was Messieurs Dumon et Cie (Dumon and Company), who were biolermakers (chaufourniers) near Tournai. I was able to find this company listed in 1906* as “chaufourniers et maîtres de carrières” as well as working with “ciment hydraulique.” So, forty years later this company still performed work as boilermakers and quarry masters, as well as cement work.

And, for those who do not know, boilermakers were often involved in the making of the large tanks required for steam engines. But, they could also be involved in a wide range of iron work.

*page 1037 of the 1906 Annuaire Almanach du Commerce de l’Industrie by Didot-Bottin.

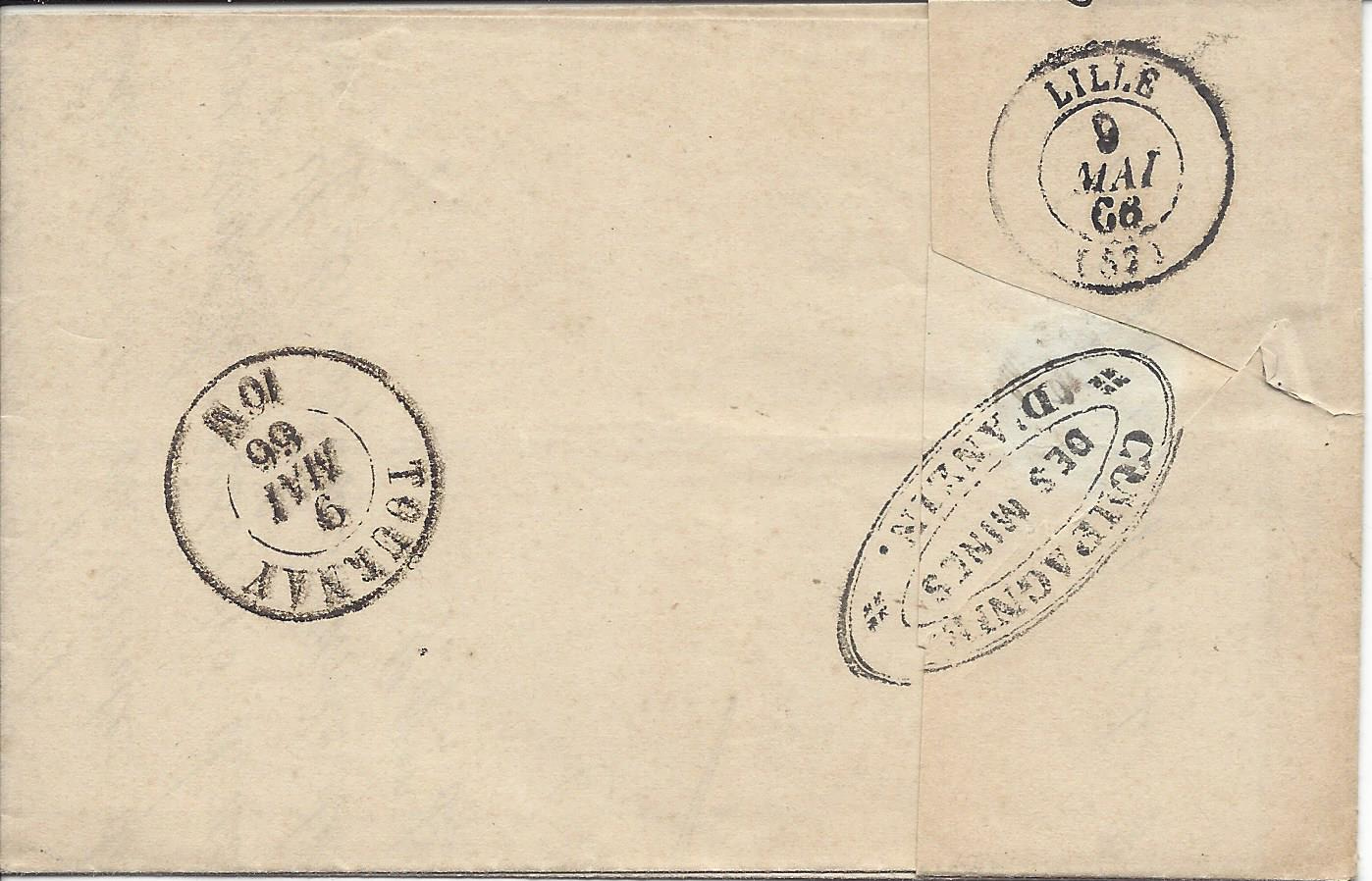

The back of the folded letter includes transit postmarks for Lille (France) and Tournay (Belgium). But, it also includes a business marking for the company that sent this correspondence to Dumon and Company.

The Companie des Mines d’Anzin was, as you can guess even if you do not read French, a mining company near Anzin in France. This large mining company was established at Anzin in 1756 where it mined coal that was initially primarily used by blacksmiths. It remained in business until France nationalized mines in 1946.

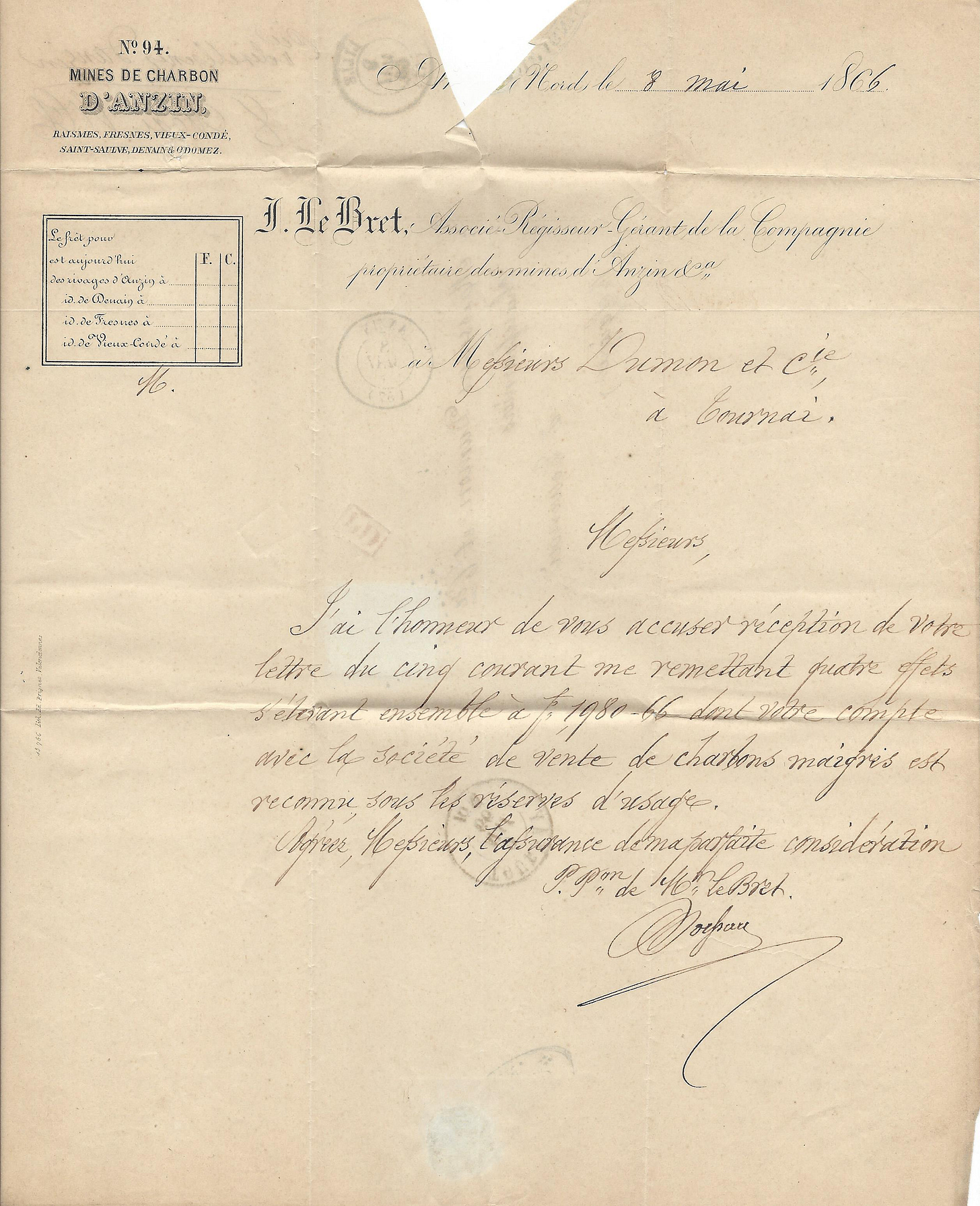

The content is short and to the point:

J'ai l'honneur de vous accuser reception de votre lettre du cinq courent me remettant quatre effets s'elevant ensemble a Fr 1980-66 dont votre compte avec l societe de vente de charbons maigres est reconnu sous les viseries(??) d'usage.

It seems that Dumon and Company had four purchases of “lean coals” from the Anzin mining operations and this is simply an acknowledgement of those amounts and that payment would be handled in the “usual way.”

A significant portion of postal history available to us during this period is similar in nature. They are records of sales, fund transfers, sales promotions and business proposals. Sometimes you might find evidence of dissatisfaction in transactions that might lead to more semi-personal references and there are times when business correspondents will mix personal messages with business.

I will admit that, to many of us, this sort of content can be unexciting and uninspiring. It’s just a business transaction. But, it’s a business transaction that reminds us that the age of steam was at its height with steamships and steam engine trains. It can also remind us of the struggles of coal miners with poor pay and difficult working conditions.

We can expand the story by exploring strikes at French coal mines, or we can look at it from the business side and discover that French entrepreneurship was fundamentally different from what we might have found in the Unitead States. These things give us a picture of how people lived and worked at the time and places that this letter highlights with its very existence.

I don’t know about you, but I think that has some real potential!

A Personal Letter from 1845

Most personal letters in the early to mid 1800s were mailed between people who were affluent. When envelopes and covers were released to the collector market from these correspondences, the families often opted to maintain control of the contents or offer that control to a museum, library or school. In some cases, covers were sold only on the condition that the addressee (and sometimes the address) be obliterated so it could not be easily read.

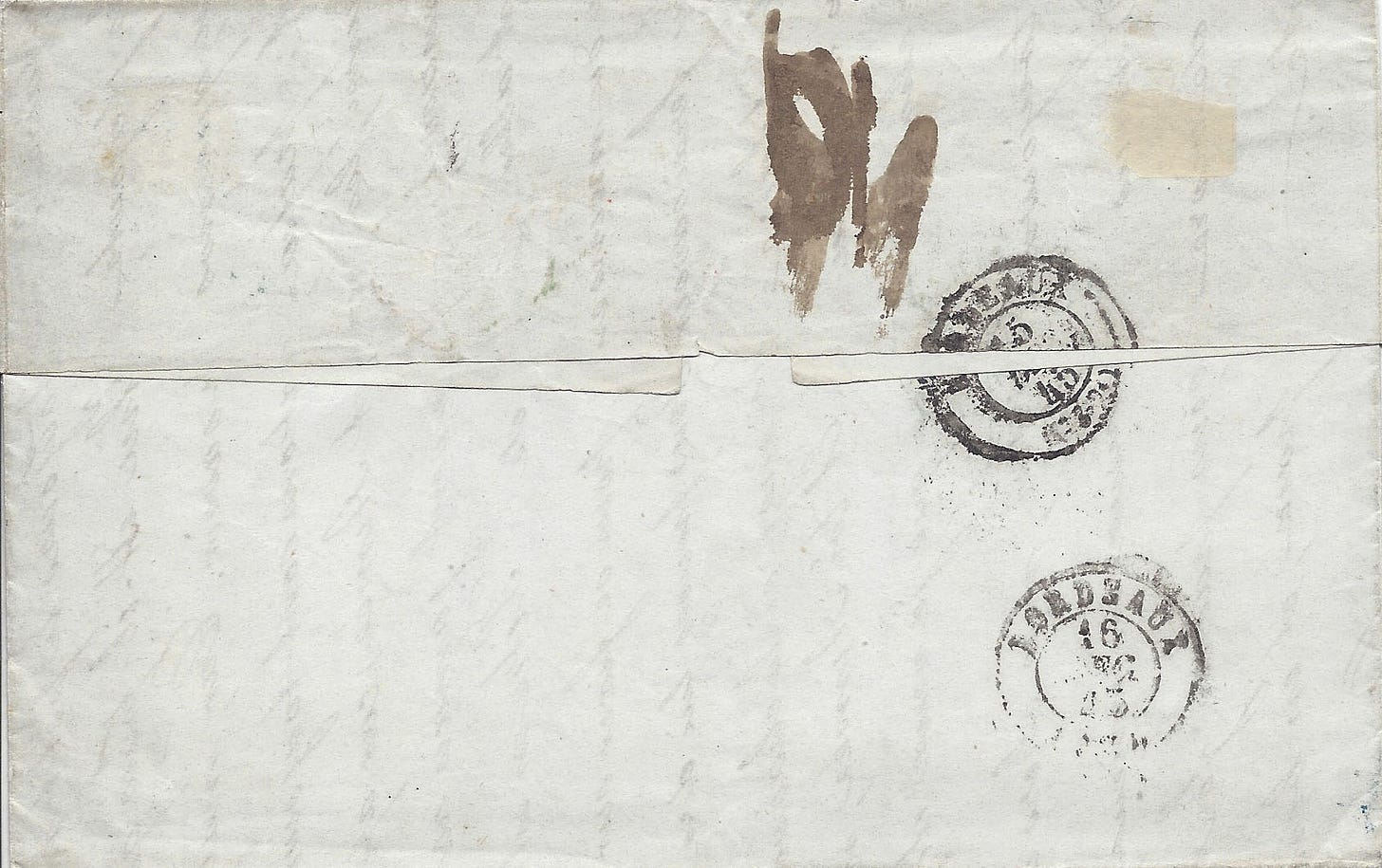

All that said - I thought I would share a piece of letter mail that did have a personal letter in it! This item went from Brussels (Bruxelles, Belgium) to Bordeaux (France) in December of 1845.

At this point in time, it was common to simply fold up a piece of paper or two and address the outside (keeping letter content on the inside) rather than use an envelope. Sometimes these folded letters were sealed with wax, sometimes they were not.

Let’s start by reading this cover and see how it got to where it was going. The markings on this cover are as follows:

Bruxelles Dec 11, 1845

Belg Valenciennes Dec 13 (in red)

B.3.R. (in green)

Bordeaux Dec 15, 1845 (on the back)

Bordeaux Dec 16, 1845 (on the back)

"14" decimes due at Bordeaux (the pen marking that looks a bit like "1n")

How It Got There

In 1845, railroad development was in the early stages for both Belgium and France. Belgium was looking to create some main lines crossing the country both from North to South and East to West. France, on the other hand, opted to create a 'star' configuration with nearly all lines starting or terminating in Paris. At the time this letter was mailed, it likely took a train from Bruxelles to the border. There may also have been some train carriage from the border to Paris. At any point in between, where a rail line was not ready, this letter was carried in a horse-drawn mail coach.

How Much Did It Cost to Mail?

In 1845, each separate postal service would indicate how much was due for their services and the amount would be totaled up to be collected from the recipient. It was understood that the postal service that collected the money would pass the proper amount back to every other postal system that participated in getting the letter from here to there.

In the case of this letter, there were only two postal services (Belgium and France) involved in the calculation of the amount of postage due.

This letter was sent unpaid from Bruxelles and 14 decimes (140 centimes) were due on delivery of this letter at Number 11 rue Plantey in Bordeaux, France. The big, bold scrawl that shows up front and center on this letter is actually the number "14." Yes, I know it looks like "1n," but use your imagination a bit and I think you can see how this would be a "14" written by a clerk who did a LOT of this kind of writing and was trying not to lift the pen off the paper any more than necessary.

The postage was comprised of two parts:

Belgian postage: 4 decimes

Belgium was separated into three rayons (regions) that represented the distance from the border with France. Brussels was in the third (and furthest from the border) rayon, which required the highest rate of 4 decimes.

Did you notice that "B.3.R" marking? That stands for "Belgium, 3rd Rayon," this was a message that helped the postal people to determine how much needed to be charged of the recipient for Belgium's portion.

This method of determining the Belgian postage due for letters to France was actually set by an 1828 agreement between France and the Netherlands. At that time, Belgium was part of the Netherlands. On January 10, 1831, the powers of Europe ratified Belgium’s declaration of independence. But, when it came to postal matters, Belgium and France simply continued to process mail as it had before by simply adopting the three rayon system establish by prior agreement.

French postage: 10 decimes

French domestic rates were based on distance and weight. The distance this letter traveled in France would be from the border with Belgium (Valenciennes) to Bordeaux (nearly 800 km).

The internal French postage rate for each 7.5 grams of weight was established in January of 1828 was 1 franc (100 centimes) for internal mail that traveled 750 to 900 km.

Letter Contents

This appears to be a letter between brother and sister with the family name Vigneau. The handwriting is remarkably clean. However, just like any handwriting that is not known to you, there are spots that I have difficulty deciphering what was exactly being said.

Below is an attempt at translating the first portion of the letter from French to English. Of course, if someone can do better with the translation, I am happy to hear corrections! It appears to be largely an attempt to get news and gossip about people the writer knows in Bordeaux.

"I wrote to Chatelie, and received a letter from him. He is doing well and gives you a thousand compliments. He is preparing to come around the month of January. I think I will do the work for him. Tell me, my dear sister, what the chronicle says about me when I left Bordeaux. Are you still on good terms with dear Marguerite? Finally, do you live together taking the long winter evenings?

Does Basterre always come to ?? talk about his decoration does he always make the little ??? that Aimee is counterfeit? And is Pechru more cheerful? These are things I want to have knowledge of...."

Who were the Vigneaus?

It is possible that these people are descendants of Gabriel de Vigneau who established Vigneau de Bommes (southeast of Bordeaux). The estate apparently changed hands in 1834 to Madame de Rayne, so the family was unlikely to be directly involved in wine making at the time of this letter. However, they were probably a family of some means and it is possible that further searching could turn up more information - though I have yet to get much beyond this point.

Wouldn't it be interesting to find copies of the "Chronicle" mentioned in this letter and see if there was discussion of the departure of the writer? And I wonder - was Pechru ever cheerful? And why was Aimee thought to be false?

We will likely never know any of these things ourselves - and yet, it is still fascinating to be transported back to 1845 and witness simple gossip and conversation between siblings.

Thank you for joining me and I hope you have a fine remainder of your day and a good week to come.

Additional Reading

If you haven’t had enough, here are some additional related entries you might enjoy:

You Own Me One (or more) - PHS #111

Something More… - PHS#120

New Language - PHS#22

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack. And, some publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest.