Welcome again to Postal History Sunday! This is the place where I get to take a look at something I enjoy every week and, in the process, we all might get to learn something new!

This seems like a good time to remind you that I am always happy to take questions and/or corrections and I will even accept requests or suggestions for future writing. It does not matter if you are merely amused by the fact that someone would even bother collecting these old pieces of paper or if you are one of those people who do so. Everyone is welcome here!

Now it is time to take those troubles and worries with you as you fill in the hole for the old outhouse. Throw those troubles in right before you cap it off. Remember, you should not flush your worries down the toilet. If you live in the country, septic tanks can have enough difficulty without you adding to it. If you live in town, the city sewer people really frown on people flushing things down the tubes that don't belong there!

Grab a snack and a favorite beverage and put on those fuzzy slipper. Sink into that comfy reading space and enjoy!

These threads always start somewhere

I’ve been asked numerous times about my process for writing Postal History Sunday. Some individuals are curious as to how I decide what I am going to write about and others wonder how I approach the research required for each article. So, today I thought I would be a little more transparent with the process in hopes that it might answer those questions.

This is going to be fun or confusing. If it’s confusing, maybe we can all just agree that it is fun to be confused sometimes and we’ll leave it at that.

Postal History Sunday topics originate either with a specific cover that I find interesting or topic area that I am interested in exploring. For example, The Train Came to Street Road and Express Don’t Mean a Thing were both inspired by an item that I wanted to research. Conversely, Coming Up Short and Don’t Leave the Band are two recent examples of a topic area I wanted to write about. In that case, the covers were selected to help me highlight the points I hoped to make.

This week’s entry was actually inspired by a coin, not a cover. Which is a very different approach for me.

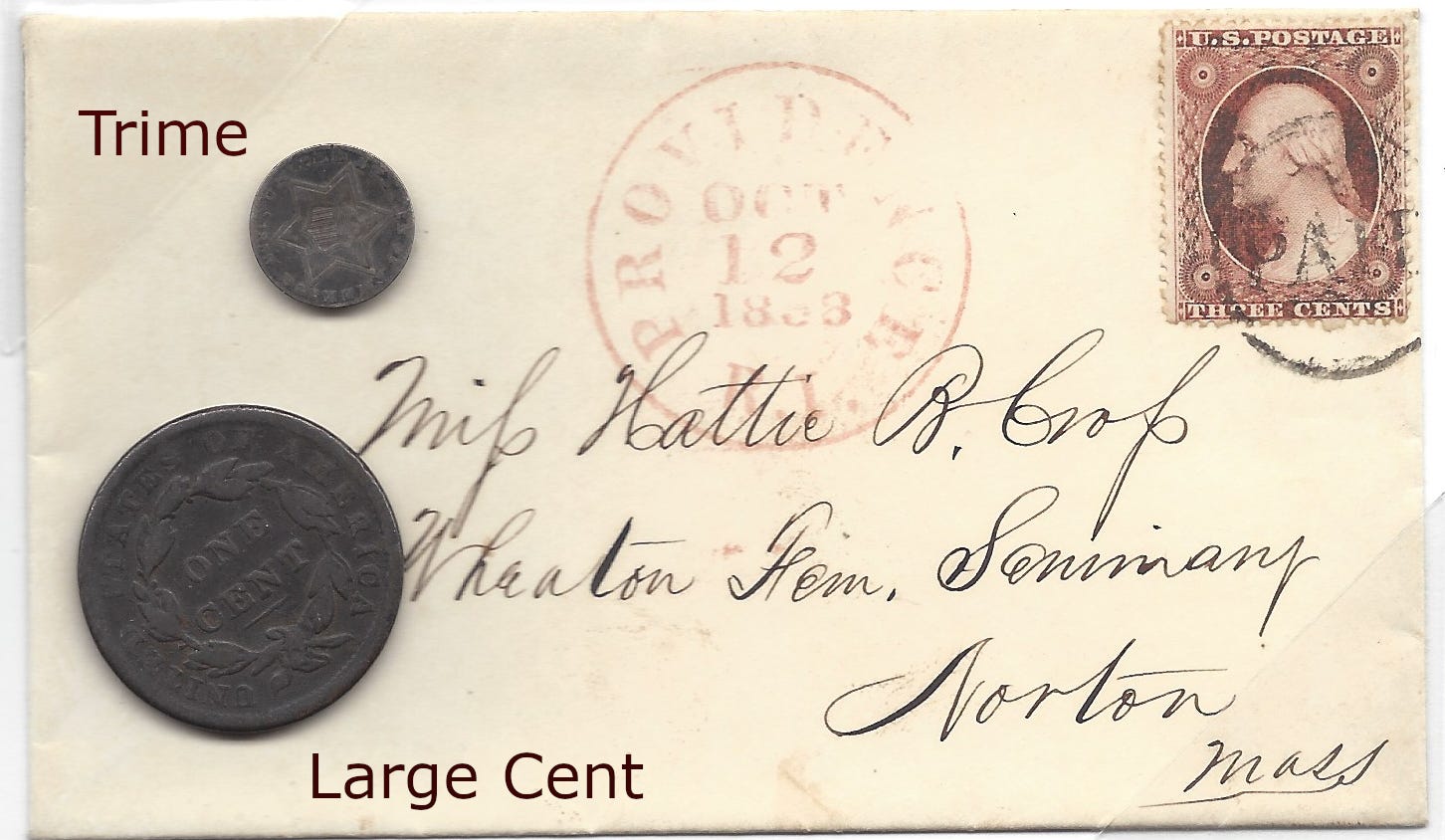

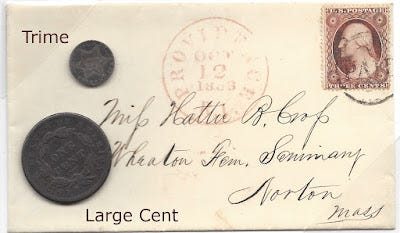

You can see the actual coin that started the wheels spinning if you view the image shown above. The smaller coin is called a trime, which was worth 3 cents. The year date on that coin is 1858, so I looked for a cover that was mailed during that year for three cents. Once I found that, I felt like I had enough to start the process of outlining an article.

Sometimes I follow my initial outline carefully. This is especially true when I have a topic I want to explore. But when I am inspired to write about an item, I find that my outline is often challenged by the things I discover as I perform the research.

The thread always starts somewhere, but I don’t always know where that thread is going to take me until I reach the end of it.

The process of reading a cover

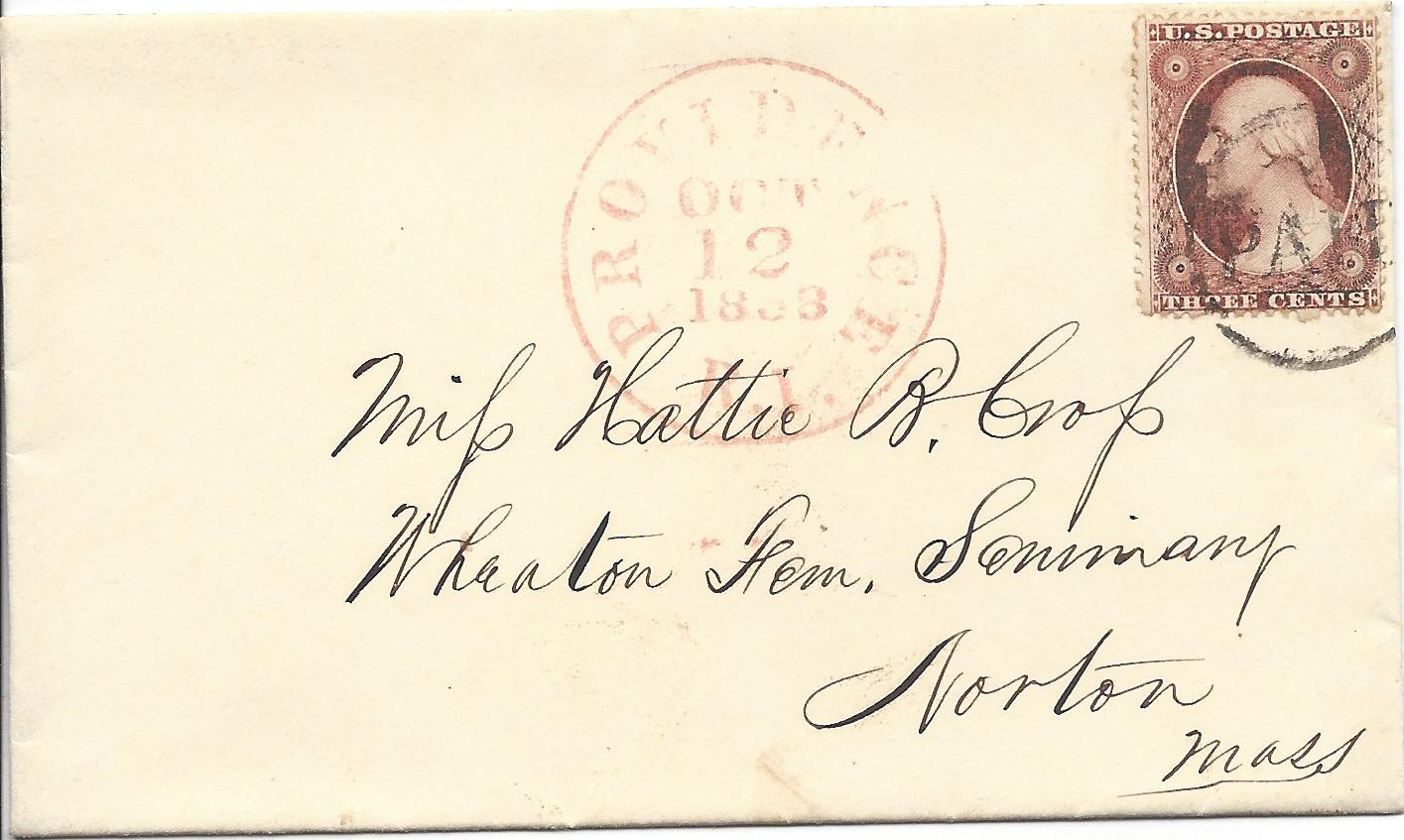

Let me start by taking the coins off the cover so you can see the entire front of the envelope. When I first look at a piece of letter mail, my initial goals are to determine each of the following if I can:

when was it mailed?

what was the origination point?

where was it destined to go?

what postage was paid and how much was required?

is there anything that here that rouses my curiosity?

It’s a short list and may not seem all that inspiring. In fact, the first four questions are simple fact finding that establish a base line I can work from. If I can’t answer those questions, it is unlikely that I’ll be able to do much more. The final question, of course, is what leads to the deeper explorations that lead to weekly articles on Postal History Sunday.

The envelope is clean and shows a nice, red City Date Stamp (CDS) that reads "Providence, R.I., Oct 12, 1858." This letter required 3 cents in postage to cover the standard letter rate inside the United States for an item that weighed no more than 1/2 ounce and traveled no more than 3,000 miles (letters to and from the West Coast required more postage).

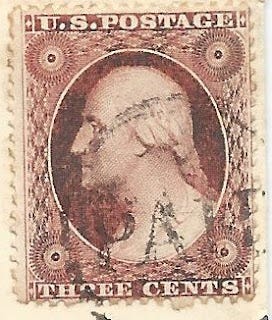

A three cent stamp was placed on the envelope to show payment for the domestic mail service. The stamp itself was defaced with a circular marking in black ink that reads "PAID." We often refer to the postal marking that was used to prevent reuse of a stamp as a "cancellation device" or "obliterator."

The postage stamp is a design that was first issued in 1851, but this particular stamp is part of a series known as the 1857 issue of US postage stamps.

Leave it to a collector to make things more complicated!

A quick look at the stamp

Collectors can be interesting creatures because they can find all sorts of ways to see differences where others do not. I mentioned that this is known as an 1857 issue of the stamp and I know that because the edges of the stamp are "perforated" rather than showing a straight edge that would have indicated it was separated from a sheet of stamps by a knife or scissors.

In 1857, stamp production added perforations to allow people to separate stamps more easily without employing a tool. Rather than develope a series of new images for this series, they simply used the 1851 designs and added the perforation process.

For comparison, this cover features a stamp with the same image (with a slightly different ink color), but no perforations. There are no perforations along the outside edge to aid in the separation of stamps from the sheet and the letter was mailed prior to 1857.

Perforations on stamps are actually a pretty amazing innovation and worthy of recognition. Postage stamps were still a relatively new item (1840 for first postage stamp in the United Kingdom and 1847 for US). The introduction of perforations to make the use of these stamps more convenient (1854, again in the UK) reflects growing demand and use of the postal services as postage rates rapidly declined and became accessible to more of the public.

I could go even further and tell you that the postage stamp on our featured cover has a small design difference that designates it as a "type II." If you look at the vertical line at the top left of the stamp you will notice that it looks like it will continue on to the next stamp that would have been above it on the sheet. This is a key characteristic for one of these 3 cent stamps to be identified as a type II stamp.

But, maybe that's getting too far in to the weeds for today?

So, now we need to climb back OUT of the weeds....

Despite our little diversion, I can tell you that our featured cover is typical in all respects for letter mail of the time. The stamp and cover are nice enough, but I detect nothing particularly wonderful if I wanted to use it to write a stand alone Postal History Sunday article.

But, sometimes the content of the cover or the addressee give us some interesting insight.

The address might be of interest

The contents of this letter are no longer with the envelope, but we can look to the address and see if there is anything that grabs our attention. The Wheaton Female Seminary in Norton, Massachusetts sounded familiar, so I thought I'd take a quick look and try to figure out why I remembered that location and school.

It turns out that Wheaton College is now a co-ed, liberal arts institution with somewhere in the neighborhood of 1700 students. Wheaton started as a college for women, established in 1834/35 as a memorial to Elizabeth Wheaton Strong by her parents. The college maintains a page summarizing this early history. If you wish to learn more, that is a good place to start.

There is actually another reason why this particular address rang a bell for me. One of the running jokes I have with my partner, Tammy, is that I know all sorts of odd little facts because...it was on a stamp.

Mary Lyon was honored with a United States postage stamp in 1987. She was an educator, a chemist, and an advocate for the provision of learning opportunities for women and is the founder of Mount Holyoke Female Seminary (est 1837). Lyon was an instructor at Ipswitch Seminary in 1834 and was asked to serve as the principal at Wheaton. She declined as she was in the middle of the Mount Holyoke project, but she recommended colleague Eunice Caldwell to serve as principal. In addition, Lyon served as a consultant for the Wheaton school as it was established.

What stood out most for me when I first read about Mary Lyon many years ago was that she wanted Mount Holyoke to be accessible to everyone, not just the children of those who were wealthy. As an individual who started with modest means, I can personally appreciate that approach.

But this was the real impetus for this article

While I like sidetrack the receiving address provided, what really got me started looking more closely at this cover was the coin shown below. I simply wanted to pick a piece of letter mail that looked kind of nice to go with this little coin I've had stashed for years.

Coin collectors, don’t expect anything spectacular here. A few old coins are are an interesting curiosity (or extension to postal history) for me, but not much more than that.

What you see here is a coin that was minted in 1858 (hence part of the reason I picked the piece of letter mail I did since it is also dated 1858). This coin was known as a trime and represented 3 cents in currency.

The trime made its first appearance in 1851.

Hmmm. 1851? Why does that sound familiar?

An Act of Congress issued on March 3, 1851 reduced the letter rate for mail in the United States to 3 cents per 1/2 ounce for items sent no more than 3000 miles (effective on July 1 of that year). A 3 cent postage stamp was issued on July 1, 1851 to show prepayment of this rate. In addition, this act authorized the creation of a 3 cent coin (the first of its type) to provide the public with a convenient method to pay for these stamps. (*see notes at the end for more)

The simple idea that a coin would be created to facilitate the purchase of stamps to pay for the postage of letters is a compelling story all by itself. This illustrates just how important mail service had become as a primary communication method for a broad section of the populace.

The popular name for these tiny coins were "fishscales," because they were extremely thin and very small - giving a remarkable resemblance to the scale of a largish fish. You can see the trime at the top left of the cover shown above. Below it would be an example of a one cent piece (known as a large cent) that was available in the 1850s. The one-cent piece is actually bigger than a present day quarter.

Can you imagine needing three of those big coins to pay three cents versus the tiny "fishscale" that would do the same job? Personally, I would think the trime might be troublesome because it would be so easy to lose!

For those who have interest, here is a view of the other side of the trime. If you are a numismatist (coin collector) you might be tempted to point out to me that this is not the nicest example of a trime and you would be correct. But, it's what I have. It has been in my possession ever since my Dad and ten-year-old me spent hours digging through his bag of Buffalo Nickles trying to read the date on each one.

It doesn't matter what the condition is because it is loaded with personal meaning - and now it has an envelope to tie it to the primary purpose of a trime - paying for a letter to be mailed.

Bonus material

I hope you found this exploration to be interesting for whichever purpose appealed to you most. Whether it was a more transparent look at how I develop an article or the connection of coins to postal history.

For those that find the combination of coins and postal history to be intriguing, I would highly recommend an exhibit put together by Richard Frajola called Paying the Postage. I am intrigued by the fact that foreign coins were frequently accepted as payment and policy often set values for their use in the United States. If you are only interested in the trime, you can go straight to frame 3 of the exhibit. Some very nice examples of the trime can be seen there.

Addional notes

Sometimes, to keep the flow of the blog post going, I don't give every detail that could possibly be shared. And, sometimes, I provide extra information at the end for those who want them. Today is such a day!

* Section 1 of Postal Act of March 3, 1851 established "That from and after the thirtieth day of June, eighteen hundred and fifty-one, in lieu of the postage rates now established by law, there shall be charged the following rates...For every single letter...for any distance between places in the United States not exceeding three thousand miles, when the postage of such letter shall have been prepaid, three cents, and five cents when the postage thereon has not been prepaid...and every letter of parcel not exceeding half an ounce in weight, shall be deemed a single letter..."

* Section 3 of Postal Act of March 3, 1851 provided direction that the Postmaster General should create "...suitable postage stamps, of the denomination of three cents...to facilitate the pre-payment of postages provided for in this act."

* Section 11 of the Postal Act of March 3, 1851 stated that "...it shall be lawful to coin, at the mint of the United States and its branches, a piece of the denomination and legal value of three cents...it shall be a legal tender in payment of debts for all sums of thirty cents and under..."

The three-cent 1851/57 stamp design has caught the attention of many collectors, past and present. If you would like to learn more, you can visit the resources put together at the US Philatelic Classics Society site. Like so many things in postal history and philately, you can dig as deep as you wish or you can explore as broadly as you want. And that is part of the reason I enjoy this hobby.

Thank you again for joining me for Postal History Sunday. Have a great remainder of your day and a fine week to come.

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack. And, some publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest.

Wheaton is Elizabeth’s Alma matter. Interesting that colleges started as Seminaries.

I wonder what people will say about how live in 100 years…

A really fascinating post (no pun intended)!!! I wanted to suggest a topic for a future article - the abolitionist mail crisis of 1835. Are you familiar with any philatelic resources regarding this event? I wish you & your family a very happy Easter! I am very grateful for your postal history writing.