This and That

Postal History Sunday #207

Every so often I find that I have accumulated a critical mass of additional notes or thoughts about previous Postal History Sunday entries. Some of those thoughts come from other individuals who have been kind enough to share them with me. When the pile of “this and that” meets up with a week where I am just not feeling quite like pushing through a brand new topic we get something like today’s entry.

You can think of it as a space management technique for Postal History Sunday. I need to empty some brain space that is holding all of the odds and ends I have been picking up. The good news is that there is a weekly “space” where I can arrange and put those things into a form that should be interesting and enjoyable for you to read. And, while I fill this space with the stuff taking up the brain space I also give myself some room to build up energy and accomplish some research for future articles.

When A Cut is Just A Cut

I received an excellent question from an individual who made it clear to me that they were NOT a postal historian, nor were they inclined to become one. However, they still enjoy Postal History Sunday! I’ll take that as a tremendous compliment.

So, here is a quick “shout out” to you and everyone else who reads this blog and still derives enjoyment from it even if you are not inclined to be involved in the hobby yourself! Thank you for participating and giving PHS your support.

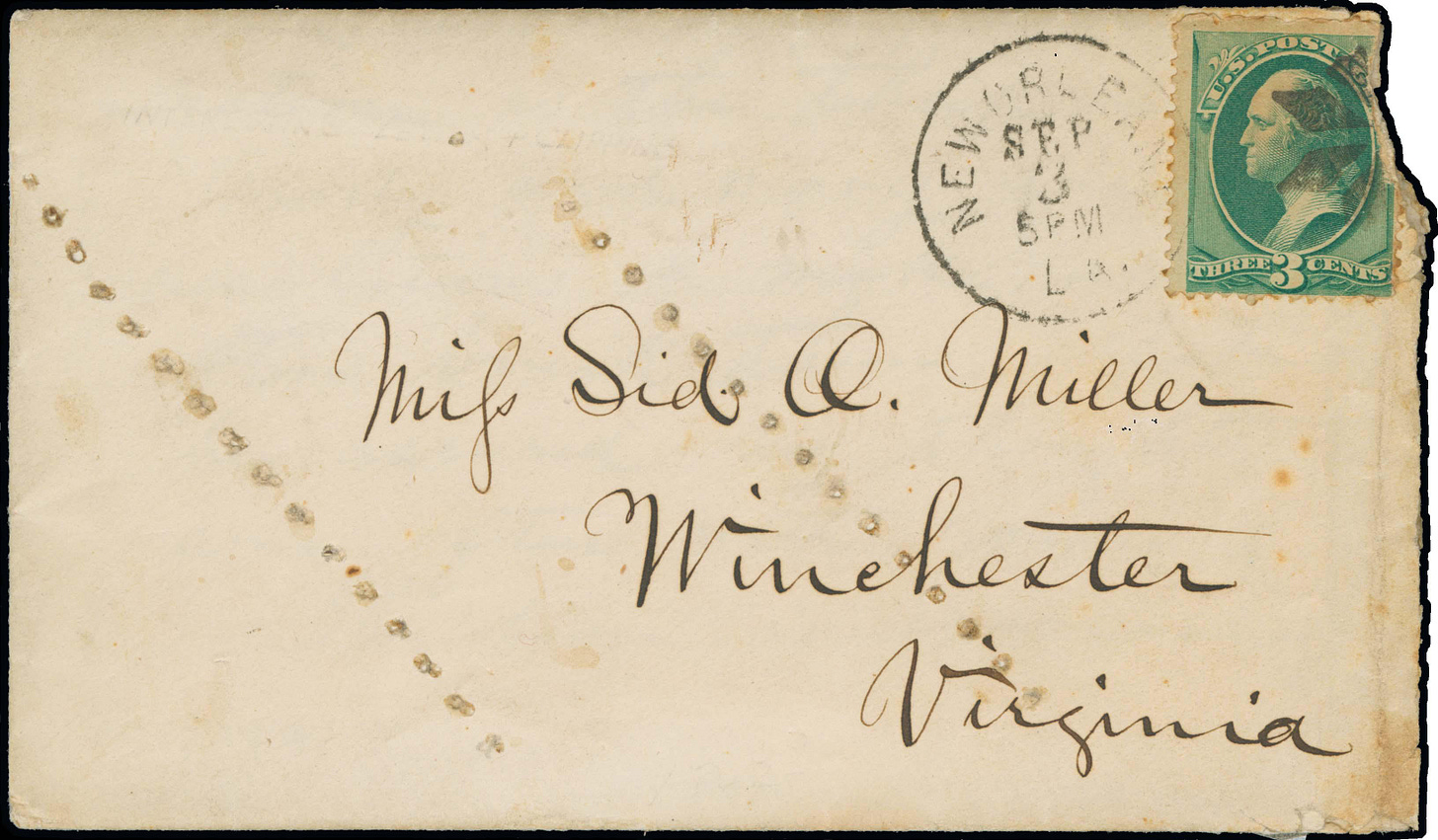

The question was: “How can you tell if a cut in an envelope (or any cover) is there because the letter was disinfected. And, other than the irradiated mail, has the United States disinfected mail?” This question came in response to last week’s article Smoke and Mirrors.

The answer to the first question is one of those “when you know, you know” things. In other words, it gets easier after you have had the chance to look at several disinfected covers that others have identified. The experience of observing the characteristics of most disinfected mail helps a person to develop the skill. As an example, I discovered one item was disinfected after I had it in my collection for several years. I did not know that it had gone through this process when I acquired it. And, in my defense, the person who had it before me did not know either.

However, there are some basics that can help us get started!

Shown above is a heavy letter (double rate) letter sent from Marseille, France to Naples, Italy, in March of 1872. Before you start anticipating me too much, this is NOT a disinfected letter. It illustrates for us the idea that the first clue we can often use is the date the letter was sent.

While the Fourth Cholera Pandemic was still going (1863-1875) it had past its peak in Europe, Italy lost 117,000 lives in 1867 but the issue was largely past in 1872. * At the time this letter was sent, cholera was doing most of its damage in North America. While this does not eliminate the possibility, it is certainly more likely to find a disinfected cover during periods when there was high disease pressure.

*from Byrne JP (2008). Encyclopedia of Pestilence, Pandemics, and Plagues: A-M., p. 107

Not every method of disinfection required some sort of damage to the cover. But it is very difficult to determine and confirm that an item was disinfected without some sort of evidence. Our usual clues are postal markings and/or slices, holes or staining that were acquired during the process of disinfection.

But, not every bit of damage on a letter is going to be caused by disinfection processes. For example, the diagonal slice near the center of this folded letter was most likely created by the recipient as they used a sharp object to help open a letter that was held closed by a wax seal (note the red). And remember, paper items that are one hundred, or more, years old have had numerous opportunities to acquire more “character” in the form of tears, stains and missing parts.

That brings us to a third clue that is fairly consistently helpful. When mail was disinfected by the authorities, it was most typically done at the destination (but not always - keep reading!). It helps to remember that, starting in the mid 1800s it was becoming clear that disinfecting letters did very little to halt the spread of disease. However, the populace often pushed for visible signs that efforts were being made by authorities to protect them from disease coming into their communities.

All of this brings us to the second part of the question.

Yes, the United States did use various techniques in an effort to disinfect the mail during its history. This article by Carol and James Millgram gives a nice overview and includes some images that might be of interest to persons reading this article.

If you would like even more detail, this article by Emmet Pearson and Wyndham Miles in the Spring 1980 Bulletin of the History of Medicine provides some interesting things to consider. The list at the end of the article is not, of course, exhaustive, but it gives a good idea of the range of diseases that prompted disinfection (yellow fever, smallpox, cholera, etc) and the techniques used (baking, exposure to sunlight, dipped in vinegar, fumigation, etc). For example, mail departing Leprosariums (leprosy) on the island of Molaka’i and the town of Carville, Louisiana, used an electric bake oven to sterilize their mail until 1968. This gives us an example of mail being disinfected at the origin, rather than the destination!

See? I told you I’d get to that!

The sporadic occurrence of mail being sanitized and the hit or miss methods of disinfection - everything from just letting things sit for a while to fumigating with formaldahyde gas - is a reflection of the uncertainty and misconceptions surrounding the spread of disease. Many influential thinkers forwarded the idea that cholera was not contagious. After all, doctors could treat patients and not risk falling ill. As a result, a theory was promoted that persons who engaged in poor moral or physical behaviors or had undesirable cultural practices were more likely to contract cholera. How else could you describe the odd patterns of disease occurrance?

Certainly, those who were poor and lived in densely populated slums were much more likely to contract cholera. To some, this seemed to prove the point to some thinkers of the time because a person in these slums was probably morally bankrupt or engaged in making bad decisions. They reached these conclusions while either being ignorant (perhaps willfully?) of the differences in living conditions or they did not understand how overwhelming poverty can be.

In the end, it was discovered that cholera was a disease that was contagious via a specific microorganism that was spread by feces - often via poor drinking water sources. So, of course, those who were less affluent were less likely to have access to clean wells and quality sewer systems, making them more likely to succumb to the disease.

Ooopsies Happen!

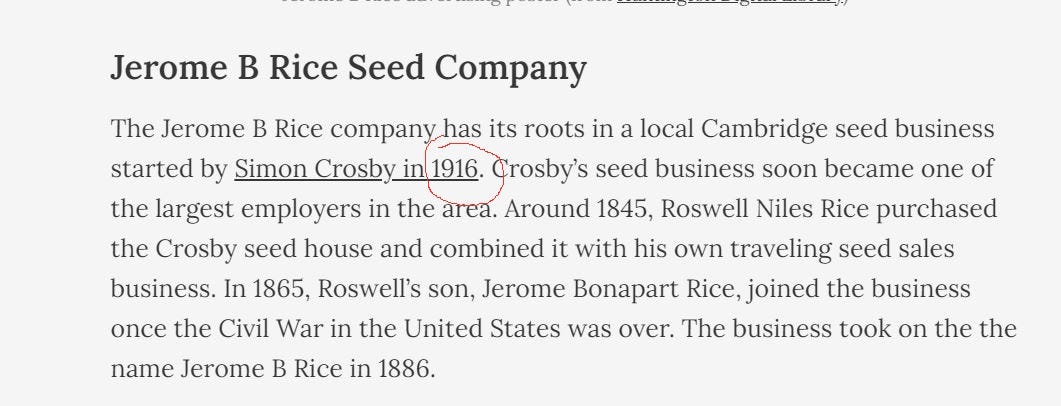

Every so often I get a correction from persons who read Postal History Sunday. And, after I get done berating myself for missing the error or for not learning or confirming the things I should have learned or confirmed before writing that particular thing, I am always grateful. As an example, I provide you with the image above provided by Mike L.

Mike was giving me much appreciated encouragement that, while he was usually silent, he did read (and read carefully) Postal History Sunday and he did appreciate the work. He very neatly circled the date “1916” in the text from the post titled Spring Has Sprung and noted that I probably meant “1816.”

What’s 100 years among friends?

If you take the link now, you’ll find that I’ve fixed that date. Once an error is found, I have a hard time letting it go. And now I am afraid you’ll all take this as a challenge and go over that Postal History Sunday and find ten more errors.

I guess if you all collectively do that I’ll have to swallow my pride and remain grateful. But you don’t know how difficult it has been to not spend a chunk of time proof-reading it just one more time…

I also received some commentary from Abhishek Bhuwalka, who is also a Substack author and writer, and who has been published in several paper journals. Abhishek was kind enough to send a couple of suggested corrections for the steamship routes from the Suez to India, Galle and Australia that I referenced in The Difference a Day Makes.

The topic itself will likely require an entire Postal History Sunday, so I won’t attempt it here. However, this is one of those instances where a weekly article that tries to reach a broad audience can be difficult to write when it comes to the finer details. Decisions have to be made about what to include and what to gloss over. But, that’s okay! It’s my goal to keep learning and keep finding ways to accurately and clearly share with a wide audience. It’s only natural that there will be topics that I will need to work on further and I welcome the challenge.

This is also a reminder that things, like mail routes, did not stay static for very long. What might have been true in 1857 might not be in 1867 and so on. It’s just an extra part of the challenge for postal historians.

As it stands, I will make a couple of word “tweaks” to that article so it is a little more accurate, but I do feel that adding too much detail there will obscure the intended point.

If you have interest, this article by Abhishek explores a sailing route covered by the Peninsular and Oriental Steamship Line from India to the Philippines. I appreciate how they locate period resources to help corroborate the content of the article!

There’s Always More to Learn

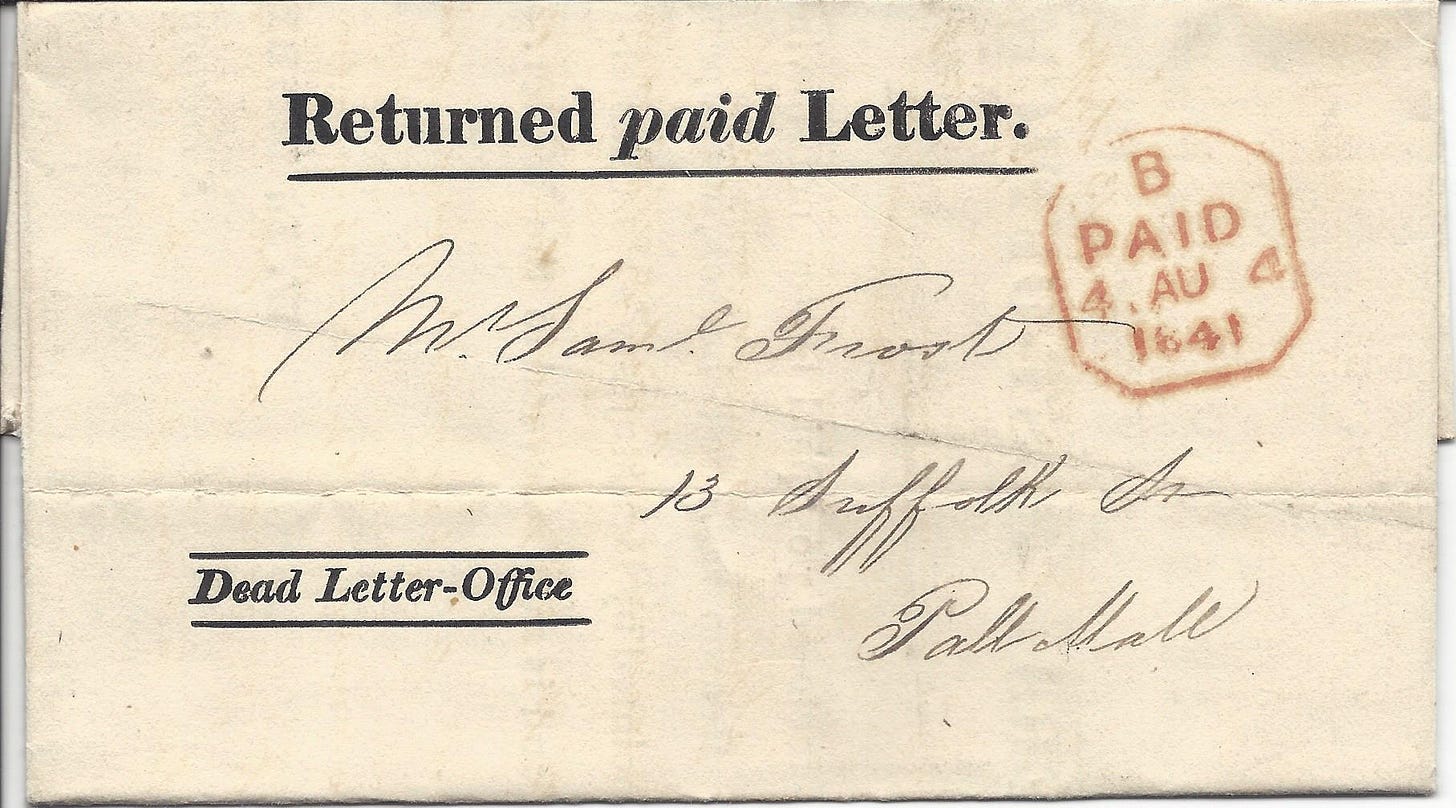

Postal History is a very large subject area. Certainly an individual can develop general competence and not be completely lost in most sub-topics. But, that’s different than having strong expertise in each area. For example, I don’t pretend to be a top expert for disinfected mail, but I can hold my own reasonably well. Another topic I am reasonably good at is dead letters. But, I readily admit that there are others that know far more than I do. I can also tell you that when it comes to Swiss mail, Roger Heath knows far more than I probably ever will.

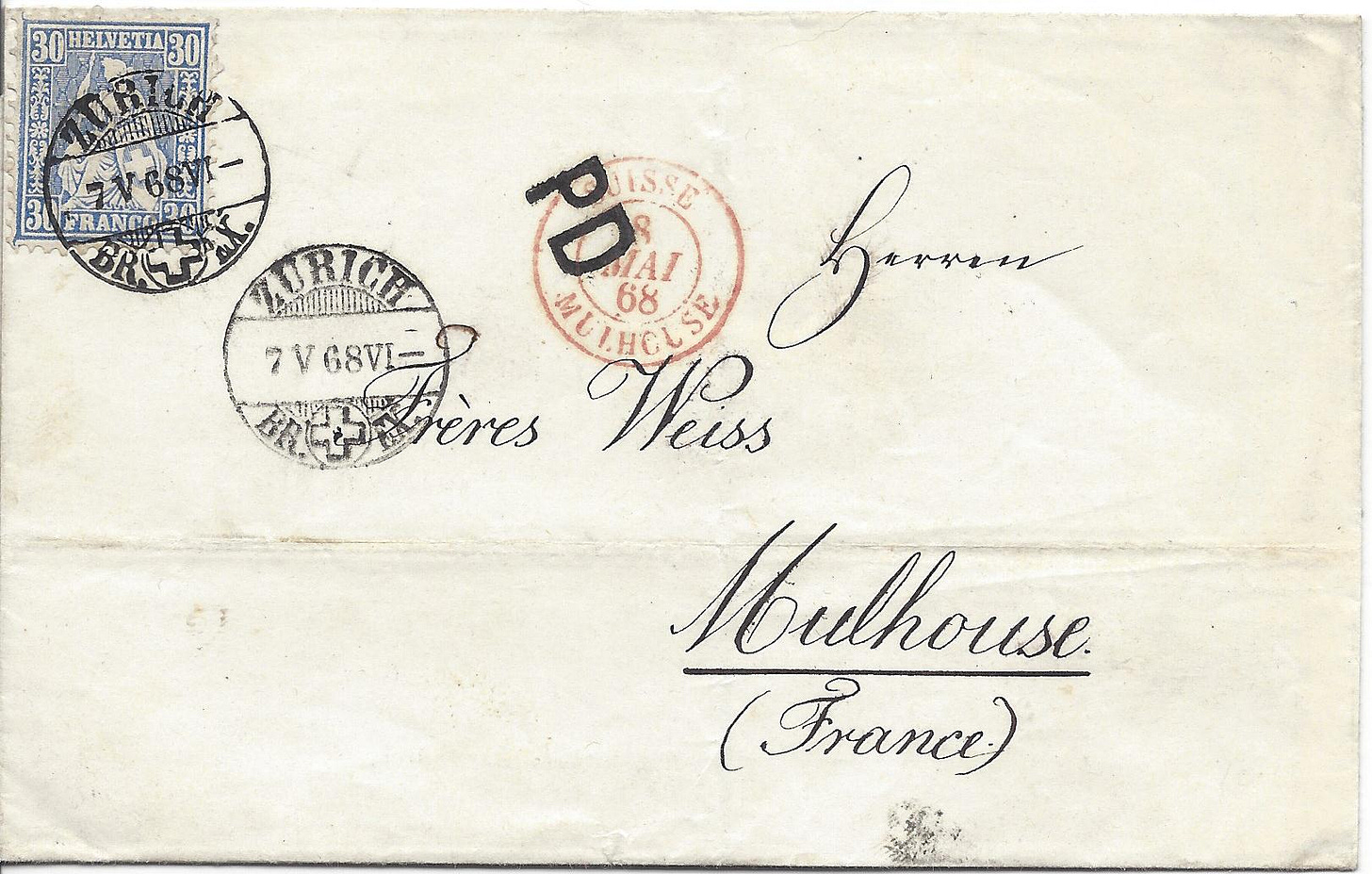

Happily, Roger shared some interesting information in response to PHS #204, It’s Worse Than That Jim, that I thought I would pass on to all of you.

The examples of dead letter mail I showed in that article were sent to Dead Letter Offices in London. In the United States and the United Kingdom, underliverable mail (dead letters) were sent to a limited number of special offices that processed these items. Switzerland, on the other hand, returned all non-deliverable items to the post office of origin. If that failed to find the sender, it would then go to the main District office. But let me use Roger’s words (lightly edited) to make the point:

In Switzerland, any non-delivered items were returned to the post office of origin - thus the reason Swiss mail typically has remarkably clear cancellations! It was presumed that the local office was the most likely place that which would accurately recognize the sender. So, whether the mail was sent to someone unknown, deceased, gone away, unclaimed or refused the same process was followed. If the origin post office was unable to determine the sender, then the item was forwarded to the main District office for further consideration. International mail was simply returned to city of origin.

In order to hammer this point home, please take a look at the 1868 letter sent from Switzerland to France. Take note of all of the black postmarks. Each is clearly struck. But this also explains two strikes of the Zurich postmark.

I guess I had noticed that most of the items I viewed from Switzerland had clear origin postmarks. But, I didn’t fully appreciate that their postal system had a very good reason to encourage there postal clerks to make sure their handstamps were well inked and that they took care as they put them on postal items. As a postal historian over 150 years later, I can say that it sure makes some of my job easier! I find myself wishing that the United States and many other countries used the same logic so I wouldn’t have to squint so much trying to figure out where covers came from!

For those who might like to learn more, Roger has an enjoyable exhibit that focuses only on Swiss letters that were refused by the recipient.

And Sometimes, Stories Are Shared

Every so often, a Postal History Sunday strikes a cord with a reader who then shares a story in response to the article. James Kimbrough was willing to allow me to share his response to It’s Worse Than That Jim.

And no, the title of that Postal History Sunday was not intended to reference Mr. Kimbrough! I am guessing those that know Star Trek were not confused by the title. If you do not know Star Trek, then you should not worry about not understanding the reference. It’s just me trying to be clever again. It’s a disease - and I am pretty sure it’s not contagious.

Jim’s story follows (lightly edited):

My father was a Master Journeyman Ironworker assigned by his union to help the USPS with construction of the first Bulk Mail Center in Jacksonville, Florida. He described his work as a daily effort to fine tune a large building with conveyor belts moving at various speeds in every possible direction. Packages of every possible size spewed from variously (un)controlled directions, frequently relying on the pull of gravity.

As I recall him saying, it was quite an experiment. With OCR (Optical Character Recognition) in its infancy at that time, there was yet much to be learned.

Now to the punch line. A few years after my Father's passing, I received a nicely packaged, in plastic to ward off any uncontrolled effects of weather in my driveway, gift from the manager of a bulk mail center in the midwest US. Inside the package was a slightly mangled letter from Dad which had escaped the fouled works of processing and fallen to the floor beneath the forest of conveyor belts in his bulk mail center.

The letter lay in the oily, dusty dark for a few years. "Dying", as it were, but not yet "Dead"! Once it was discovered, the US Postal Service clung to the postman's oath - by God this letter was going to find it's way home come hell or high water! Almost like a dutiful Postmaster of old, the manager included a written apology for HIS mail center being at fault for the delayed delivery.

I was touched by his allegiance to duty. He would get the job done, in the event that the intended recipient (me) was also not yet "deceased".

Interesting enough, Postal History Sunday #193, Time Machine, actually alludes to the OCR machines and some of the innovations Jim’s father was witnessing in his work. This gives all of you a fine illustration as to one of the benefits I receive for my work on PHS. If I had not spent some time on this topic prior to Jim’s sending his story, I might not have appreciated what he was saying as much as I do now. I mean, my specialty is mail in the 1850s, 60s and 70s. If I weren’t trying to write these articles on a weekly basis I might never have explored the OCR and Bulk Mail Centers in the first place.

Yes, I got the date correct this time. But, if I didn’t I am sure Mike will tell me (thanks Mike!). And, as I said before, what’s one hundred years among friends?

And now, my work here is done! I feel that I have filled this space and made more space in my brain for future Postal History Sundays. And, I hope you enjoyed this little diversion - at least a little bit.

My thanks to all who have contributed with your questions, suggestions, corrections, additional information, and stories. They are all appreciated.

Thank you for joining me today. Have a fine remainder of your day and an excellent week to come.

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack. And, some publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest.

Thanks, Rob. Hello from Washington State.